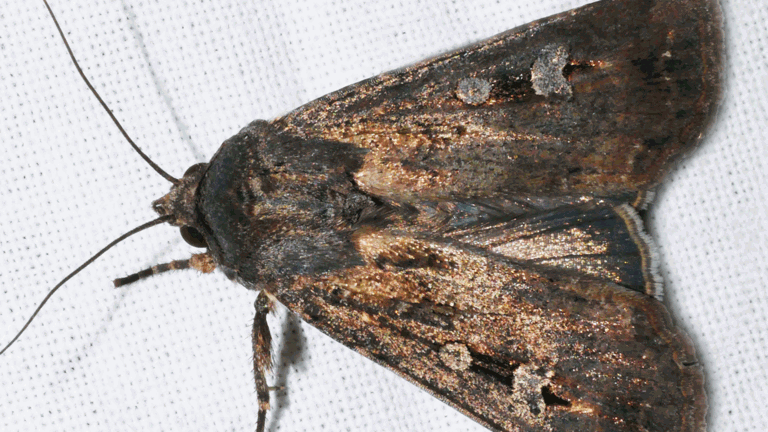

Bogong Moth

Agrotis infusa

Burramys parvus

Ski resort development may destroy pygmy-possum habitat. A study at Mt Buller showed that ski resorts have a huge negative impact on genetic diversity in the possums.

Climate change may have a devastating impact on many alpine plants and animals as the environment warms and less snow falls. A major fire in 2003 burnt much of the Victorian habitat, and predation by introduced cats and foxes is another serious concern.

Mountain Pygmy-possums

Mountain Pygmy-possums are found in alpine and subalpine regions above 1400 m on Mt Buller and the Bogong High Plains in Victoria, and Mt Kosciuszko in New South Wales. They inhabit rocky alpine and subalpine areas where Mountain Plum-pines grow.

Mountain Pygmy-possums are tiny marsupials not much bigger than mice. They have thick grey fur, a long prehensile tail, and nimble feet for grasping and climbing. They are nocturnal and secretive.

First described in the 1890s from fossil bones, they were believed to be extinct until 1966 when a live possum was found in a ski lodge. The entire range is only about ten square kilometres and in 2008, total numbers were estimated at 1700 adult females and 550 adult males.

In the brief warm months these animals gorge on Bogong Moths, seeds and fruits to build up reserves of fat. They can double their weight during this time of plenty. They also store nuts and seeds to eat during the freezing winter.

Mountain Pygmy-possums hibernate for up to seven months, curled up in nests two to four metres under the snow. During this time they drop their temperature from 35°C to around 2°C. They wake occasionally to nibble on their stored food.

Males hibernate in slightly warmer locations and rouse from hibernation before females. They scurry between boulders seeking females for mating in October or November. The females carry their four babies in a pouch until they are too large, then leave them in the nest for another month until they are weaned.

There are many types of dry forests in Victoria including stringybark, red gum, grassy woodlands and the remnants of the once great box–ironbark forests.

Victoria’s coastal wetlands are significant places for wildlife, with many listed in international conventions to protect the habitat of migratory birds.

The Victorian Alps extend from the plateaus of Lake Mountain and Mt Baw Baw to peaks such as Mt Feathertop and the headwaters of the Murray River.

When the first Europeans arrived in Victoria there were grasslands on the vast, undulating western plains, on the northern plains and in Gippsland.

The Victorian Mallee in the north-western corner of the state has a mosaic of vegetation types adapted to low rainfall and sandy soils.

Find out about the issues affecting our special places and the plants and animals that live in them, and discover some ways you can help.

We are making improvements to our website and would love to hear from you about your experience. Our survey takes around 10 minutes and you can enter the draw to win a $100 gift voucher at our online store!

Museums Victoria acknowledges the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Boon Wurrung Bunurong peoples of the eastern Kulin Nations where we work, and First Peoples across Victoria and Australia.

First Peoples are advised that this site may contain voices, images, and names of people now passed and content of cultural significance.