Uncovering the Exhibition Building's secret WWII stories

For nearly 50 years, hundreds of items lay hidden within one of Melbourne’s most famous buildings and now we are working to reveal more.

Beneath its cavernous dome and labyrinthine passages, Melbourne’s Exhibition Building harbours 150 years of secrets.

And, sometimes, the world heritage-listed building reveals its treasures in the most unexpected of ways.

In 1989, at the start of major restoration works which continue to this day, workers prized up the floorboards of the Exhibition Building’s upper level.

Museums Victoria senior curator Deborah Tout-Smith describes what they found beneath as a ‘historian’s dream’.

At first glance, it all may have appeared nothing more than a pile of rubbish: chewing gum, scraps of food, bits of paper, medical pills and ‘endless cigarette packets’.

But what turned this trash into treasure was who discarded it, and when.

From its origins hosting the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition, through the formal opening of Australia’s first Federal Parliament in 1901, to its use as a Spanish Flu hospital in 1919, the Exhibition Building has a storied history. Others chapters are less known.

In 1940, in the months after the outbreak of WWII, the Exhibition Buildings complex was requisitioned by the Royal Australian Air Force and used as a barracks and training facility.

The surrounding gardens became a hotbed of activity—playing host to regular marching drills and enthusiastic trench diggers.

By 1942 more than 2000 men of the RAAF had been stationed at the Exhibition Buildings, alongside members of the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force.

As the city toiled through air raid drills and blackouts, its dramas played out beneath the great Florentine dome.

The buildings hosted public dances and balls to boost morale, witnessed steamy affairs, unrequited love, absent family members, the loss of mates—along with the day to day struggles, milestones and triumphs of everyday life.

All the while, the space beneath the floorboards accumulated fragments of their lives.

Eventually the war ended, the troops left, and the city hummed back into normal life.

The Exhibition Building opened to new chapters.

Today it hosts exhibitions, final year exams for school leavers and university graduations, and is a favourite backdrop for newlyweds and tourists alike.

But the building did not forget the stories of its wartime past.

It held onto to them, nursing a secret time capsule, until it was accidentally revealed nearly 50 years later.

Museums Victoria collected the WWII-era detritus and began teasing out the stories of the more than 300 items that once belonged to those RAAF men and WAAAF women.

Sometimes it was deliberate—without lockers, theft was rife among the boarders and the floorboard gaps may have provided a place to stash personal items.

Love letters tell explicit stories, while liver pills and Aspros spin a more subtle tale.

What makes all these items so special, Deborah says, is that they offer an unfiltered window into the past—as it was experienced by everyday people.

Taken as a whole, it is a new version of history. Not history as told by the powerful to shape their own legacy, nor propaganda whipped up to inspire young men to enlist to serve.

‘This is the stuff of life’Deborah Tout-Smith

But for every insight into the past, offered by these accidental treasures, comes a raft of questions.

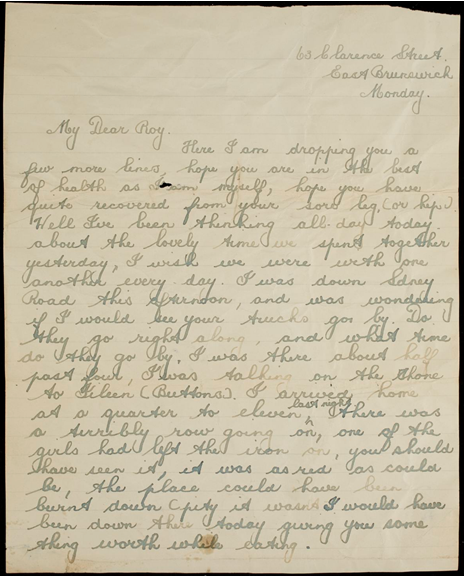

One of the gems of the collection is the Royce Phillips letters. Royce was 18 when he was stationed at the Exhibition Building and in the midst of a ‘wild romance’ with one Roma Wright.

‘She was madly in love with him—unfortunately he doesn’t seem to be as excited about her,’ Deborah says.

Of course, we can only interpret the story from the letters sent to Royce, not those he wrote himself. But soon after, Royce was seen with another girl. ‘You have to be very careful with who you mix with over there,’ Royce's father warned him.

All of which makes a juicy tale—but why did Royce push these, and other letters, through cracks in the floorboards of his barracks? What did he write in his letters? What became of Royce and Roma? Who was the mysterious other young woman?

Then there is the Dorothy Quinn dog tag mystery. Dorothy was 18 when she was stationed in Melbourne as a first aid orderly. There she fell in love, married and, in 1944, fell pregnant. She returned home to Perth as Dorothy Hubbard, leaving both her maternal surname and military identification behind her.

Did the dog tags fall through the floorboards by accident? Or did Dorothy deliberately slip them through? If so, why? Surely these would serve as a memento to a pivotal chapter in Dorothy’s life. What did those tags mean to her?

As part of the REB Veteran Stories project, Deborah and her colleagues at Museums Victoria are chasing the stories of the men and women who, like Royce and Dorothy, called the building home during the war.

But, ultimately, many of these questions can only be answered if Museums Victoria is contacted by the people who once owned these items, their family members or descendants.

Can you help us?

If you, or anyone you know, would like to share a story of the Exhibition Building during war-time, please contact Museums Victoria at Ask us, or via post:

Museums Victoria, PO Box 666, Melbourne, VIC 3001 – attention Senior Curator Deborah Tout-Smith For other general enquiries and questions please refer to Ask us

This project is made possible thanks to the support of the Victorian Government.