What’s in a name? An animal’s can be misleading

When is a tiger not a cat, a fox not a canine, and a jelly fish not a fish? Unfortunately, more often than you might think. Come for a closer look at some misleading animal names.

Animal names can be confusing business, and sometimes just outright misleading.

Did you know that flying foxes aren’t really foxes at all?

A glow worm can sometimes be a gnat or a beetle, but never an actual worm.

The Tasmanian Tiger isn’t even in the cat family.

And a jelly fish is more closely related to a piece of coral than it is to any fish.

So, why give names to animals that do not represent what they are?

Well, it has to do with some of the shortcomings of common names and why scientists are not particularly fond of them.

However, that is not to say that they are entirely useless.

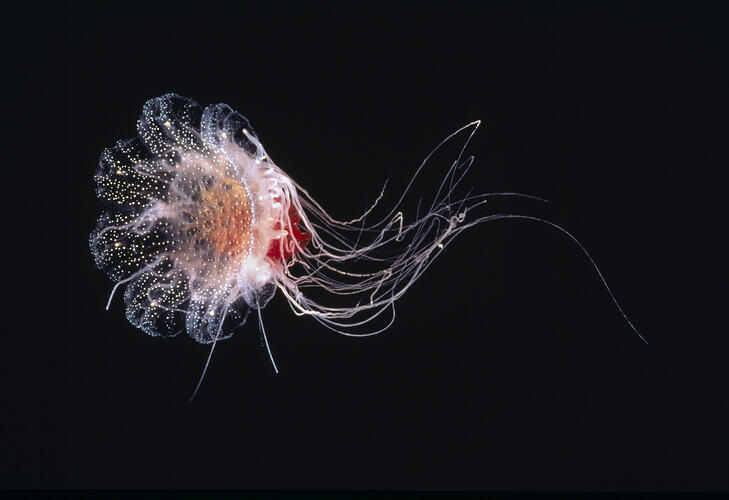

Jelly Fish

In some cases, the meanings of words have changed over time.

‘Fish’ used to mean any animal that lived in water, and that included anything from seals, to penguins, octopus, sea turtles and, of course, jelly fish.

However, we now use fish as a specific term for a group of animals which live in the water, have a bone or cartilage skeleton, and breathe using gills.

The phylum that includes jelly fish, Cnidaria (the C is silent), also includes anemones and corals.

Cnidaria are invertebrates, meaning they don’t have a backbone.

Since a bone or cartilage skeleton is a requirement to being a fish in modern zoology, jelly fish sadly don’t make the cut.

Flying Fox

If you compare the face of a flying fox and a Red Fox, it’s quite easy to see why these animals were confused.

However, this is another case of the animal’s common name not being particularly helpful to zoologists.

Flying foxes, along with other bats, are part of an order of mammals called Chiroptera; foxes are canids, the same family as dogs.

The tiny little bones of Chiroptera don’t tend to last long enough to fossilise, which makes it very hard for palaeontologists to study them.

That said, we do know that they are a very old group of mammals, that are estimated to have diverged from the mammal family tree during the Palaeocene Epoch, some 63 million years ago.

Foxes, on the other hand, didn’t appear for another 30 million years.

If we want to include foxes and flying foxes in the same group together, we really should also be including pangolins, horses, and bears (oh my!), as these animals are all more closely related to foxes than bats are.

Glow Worm

Other examples of misnamed animals have come about because the creature was incorrectly classified when it was first discovered.

In the case of glow worms, like we find in Victoria’s Otway region, these are actually the larvae of a small gnat.

Worms are a diverse group of invertebrates (animals without a backbone) that remain soft-bodied throughout their lives.

Insects, however, go through various life stages and it is during the juvenile period that they appear quite like a worm.

Insects eventually undergo a complete metamorphosis and grow a hard external skeleton, otherwise known as an exoskeleton.

In the case of glow worms, it is only the juvenile larvae that glow.

And if you did not know what you were looking at, those larvae could quite easily be mistaken for a worm.

Which helps explain why they are commonly known as glow worms, rather than their scientific name Arachnocampa otwayensis.

And, let’s be honest, glow worm just rolls off the tongue better than glow gnat.

Tasmanian Tiger

During its lifetime the Tasmanian Tiger was known by many names—nearly all of which were misleading.

It was interchangeably called a tiger, a marsupial wolf, and Tasmanian wolf.

Even its scientific name, Thylacinus cynocephalus, means ‘dog-headed pouched-dog.’

However, the Tasmanian Tiger’s comparison to wolves or dogs only exists because of convergent evolution, where species that are not closely related independently evolve similar traits.

As for being a ‘tiger,’ this is just a reference to the distinctive stripes along its back.

In reality, the Tasmanian Tiger was a marsupial and sat much closer to koalas and kangaroos on the mammalian family tree than it ever did to dogs, wolves, or tigers.

And while European colonists only found the species in Tasmania, fossil remains have been found all over mainland Australia and as far as New Guinea.

So, not only is it not a tiger, it is not just Tasmanian either!

Water Rat

Since the 1990s one Australian animal’s common name has changed considerably.

Hydromys chrysogaster, or Rakali, was previously known as the Water Rat.

And while it is a rodent that lives in water, there are some good reasons for the change.

Rakali is not in the same genus as well-known rats like the Black and Brown Rat.

The adoption of the First Peoples’ language common name—Rakali—is an attempt to reflect this animal’s unique character and place within our region, outside of the rat stereotype.

People tend to think of rats as dirty and invasive, but Rakali is native and well adapted to Australian waterways.

The updated name also acknowledges the animal was named by humans well before European colonisation.

Naming things

The science of naming and categorising living things is known as taxonomy, which aims to group them based on their evolutionary relationships.

Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus was the first to come up with this system, known as binomial nomenclature, in 1758 and it is still largely in use today.

The first part of an organism’s name is the genus (to describe the larger group it belongs to), while the second part refers to the specific species.

However, this is not set in stone.

This is because, generally, taxonomy should help us judge how related one animal is to another.

As new species are discovered, and our knowledge and understanding of biology improves over time, scientists have moved some animal groups around.

Some animals are more related than they appear on the surface, while others that look alike are not related at all!

Scientific names are not perfect

Scientific names are often constructed from Greek or Latin words that aim to describe the species.

And common names are often derived from translations of the scientific name.

Binomial nomenclature has been used to honour a particular person or, alternatively, insult a scientific rival—something Linnaeus did himself, but that tactic has now been banned.

Sometimes these names are a description of the animal’s physical features.

However, even scientific names can show us the misunderstandings and mistakes made by previous biologists.

For example, Phascolarctos cinereus loosely translates to ‘grey pouched bear’ which gives you a pretty good idea of which iconic Australian animal it refers to.

And while the Koala is not closely related to a bear, it is still commonly confused for one today.

Some names refer to a particular place, but this too can go wrong.

Due to some creative record keeping by a zoologist in 1776, the scientific name for the Laughing Kookaburra is Dacelo novaeguineae.

This loosely means ‘kingfisher from New Guinea,’ despite being the only Kookaburra in its genus not found in New Guinea.

What are scientific names for?

Despite some confusing Latin and Greek translations, scientists have good reason to stick with scientific names.

Common names can vary from region to region, and many also refer to more than one species.

We might say Flying Fox, but it is not clear which of the 60 members of Pteropus we are talking about.

‘Giving species scientific names allows us to universally communicate things about them to other scientists,’ says Joseph Schubert, a taxonomist at the Museums Victoria Research Institute.

‘It also means that they’re recognised not only in science but in legislation.’

For instance, if a species is endangered and governments want to specifically protect it, an unambiguous name is vital to differentiate it from other animals.

So, scientific names are great for clarity—especially when you are dealing with an international community of multiple countries and languages.

So which name is best?

For general purposes, we all know that scientific names can be very unwieldy.

Nobody wants to come to work in the morning and tell everyone about how their Canis familiaris (dog) kept them up all night barking at the Trichosurus vulpecula (Brush-tailed Possum) in the roof.

As a compromise, scientists are trying to move the common names of species away from their confusing misnomers.

For example, flying foxes are more likely to be called fruit bats in modern field guides.

Marine biology educators are slowly replacing the term jelly fish with sea jellies.

And modern mammalogists are known to wince when they hear Tasmanian Tiger instead of the much-preferred thylacine.

But changing language is a long and slow process, these things take time.

Unlike scientific names, there’s no central agency for common names.

Strangely enough though, most scientists seem happy to keep calling glow worms, glow worms.

Maybe they just understand that it really is quite fun to say.

And, let’s be honest, glow gnats is just never going to catch on.