Bats: the flying mammals in dire need of a PR manager

Unveiling the facts and folklore of bats—the world’s only flying mammals.

Beloved by goths, a source of inspiration for comic book heroes and the bane of the fruit grower—bats are many things to many people.

But there’s no denying they play a vital role in their local ecosystems, and Australia is home to a huge variety of species both large and small.

As a natural history museum we know a thing or two about these amazing animals.

Bat beginnings

The word bat describes a broad array of flying mammals that belong to the order Chiroptera, which roughly translates to ‘hand wing’ in Greek.

Given what they have inspired in popular culture, it is perhaps fitting that their origins are cloaked in mystery.

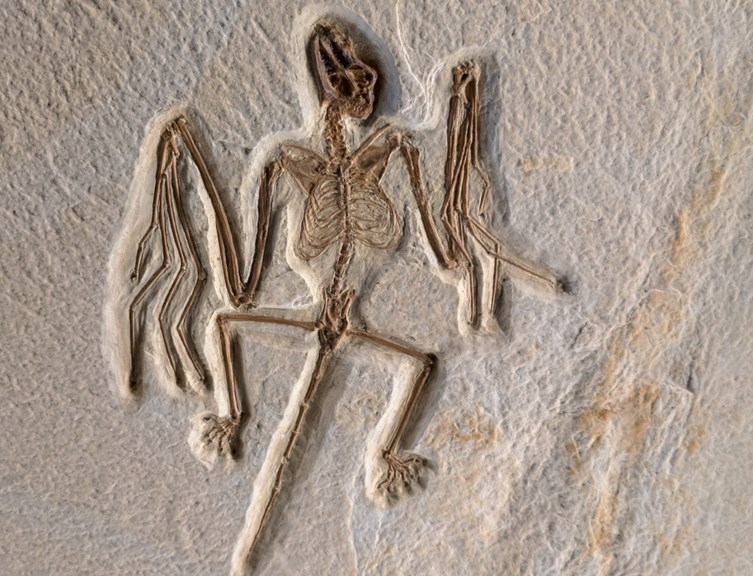

The earliest known fossil of a confirmed bat is 55 million years old, but like other flying vertebrates (the birds and the pterosaurs), evidence of these early animals is hard to come by.

Their light and fragile skeletons (and presumed life habits) make the chances of their remains lasting long enough to become fossilised quite remote.

Scientists who have examined their DNA though, think bats first appeared around 60 million years ago, after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

After the similarly maligned rodents, bats are the largest and most diverse order of mammals on the planet.

They are found on every continent, except Antarctica.

Until recently, we thought of bats broadly fitting into two main sub-orders—megabats, and microbats—but genetic studies have shown it's a lot more complicated.

The latest interpretation separates bats into Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera based on their DNA, rather than size and anatomy.

However, there is still some debate about this so for the sake of simplicity we’ll stick to mega and micro bats for now.

The taxonomy (scientific system of naming) of mammal groups doesn’t always perfectly align with their size, but bats are fairly well organised—as long as you don’t mind small megabats and large microbats.

The easiest way to think about megabats is that they eat fruit, so megabat = fruit bat.

Microbats are a little more varied in their diet and, yes, some do drink blood, but more of that soon.

Stomachs on wings

Fruit Bats, as their name implies, are largely frugivorous and generally roost in colonies in trees.

They have also been known to branch out into eating the nectar from flowers.

Their reputation as insatiable fruit-munchers is well-founded and it’s estimated they can consume over twice their normal body mass of fruit in one night!

That’s quite an effort, considering they have to fly around with all that weight, but fruit bats are quite good at offloading their cargo.

Their seed-riddled poo is vital for the distribution of some plant species (even if they sometimes stain the sheets on your washing line), and the close contact some bats have with flowers makes them important pollinators of some fruits.

Microbats, however, are even more diverse in their diet and behaviour.

The bulk of Australia’s bats reside in this sub-order but being relatively small and insect-eating, they aren’t as easily understood by the average person.

One of the smallest of these is the Little Forest Bat (Vespadelus vulturnus), that weighs only four grams!

Microbats are strictly nocturnal and generally roost in very large numbers in caves or tree hollows.

Most of these feed on insects, using echolocation to zero in on hapless moths and insects.

Some species catch their prey on the wing, like the White-striped Freetail Bat (Tadarida australis).

Have you heard an intermittent ‘ting-ting-ting’ at night?

That’s the sound this bat makes as it hunts, and it’s one of only two bats in Australia that use echolocation audible to humans.

Other bat species, like the Ghost Bat (Macroderma gigas), use their echolocation to hunt prey on the ground—a practice known as ‘gleaning’.

Some larger species of microbat found overseas have been known to hunt birds, lizards, frogs, fish, and even other bats.

Infamously, three species of microbat have adapted to feed on the blood of large birds and mammals—these are the so-called vampire bats that live in South and Central America.

However, they don’t suck blood.

They use their sharp incisors to make a small cut and lap up the blood, usually without alerting their prey.

Pointing the fingered wing

Although unfairly maligned in folklore, it is nonetheless true that bats can harbour many diseases.

They have been found carrying pathogens like coronavirus, Hendra virus, SARS and rabies, but it is important to note they are not necessarily the origin of these maladies.

Bats are what is are known as a zoonotic vector—an animal capable of transmitting diseases to other species.

Research has shown that bats don’t host any greater proportion of disease than other mammals, including primates like us.

The thing that sets bats apart is their incredible immune systems, that allow them to carry otherwise deadly pathogens, without being affected.

Bats are also highly mobile, regularly encounter other species, and have relatively long lifespans.

All of this adds up to a perfect storm for zoonoses—diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans.

However, this is not really the fault of the bats.

They aren’t inherently unhygienic (even if they do pass waste while hanging upside), nor do they actively seek out opportunities to co-exist with humans—in fact, they are uniformly shy animals.

It is only when humans create these interactions with bats that real problems arise.

This interaction can be indirect, with livestock and pets, or direct contact with bats themselves.

Deliberate exposure to bat carcasses does seriously compound the risk of disease transmission, too.

Another common fear is that bats will deliberately tangle themselves in people’s hair, but you can rest easy.

They’re a wild animal, and a bat no more wishes to be trapped in human hair than we want them to be there.

That’s not to say bats don’t sometimes become entangled, but it is usually because they’re chasing insects or other, more appetising, targets.

So, it’s best to leave any bat-wrangling to a qualified expert, like a wildlife carer

But their inherent resistance to, and co-existence with, pathogens make bats excellent allies in medical research.

Bats around the world

The Western world’s perception and portrayal of bats as a menace is shared by some cultures but is by no means universal.

In Chinese art and narrative traditions bats are symbols of happiness, longevity, and prosperity.

Sadly, in the English-speaking world, bats often are regarded with suspicion or disgust.

This prejudice dates back to a time when dark caves were considered portals to the underworld, or the land of the dead.

That association was carried over to bats because many species live in dark caves, emerging only at night to feed.

The link between bats and vampires arose from the feeding habits of vampire bats and has developed alongside western vampire mythology.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) reinforced the partnership, which that has continued with the cinematic representation of vampires.

Positive portrayals also tend towards the dark, spooky and transgressive—after all, one of the world’s most popular vigilantes is Batman.

But centuries of negative press is a difficult thing to overcome.

Exaggeration and over-reporting of bats’ negative traits has built fear and distrust, hindering conservation efforts.

Bats are an essential part of the world’s ecosystems, but they are also worth billions of dollars to agriculture—they pollinate trees and crops, while keeping insect populations in check.

So, now that you know more about how important bats are to us and our world—spread the word!

Our own iconic Grey-headed Flying Fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is vulnerable, and under increasing pressure from habitat loss and climate change.

It is vital for us all to put misconceptions about these extraordinary creatures to rest and appreciate them for what they are, before it’s too late.

Still got a question about bats? Ask Us!