Significant Mi'kmaq regalia crosses oceans and time to return home after 150 years in Melbourne

A unique regalia from Canada has finally returned home, in a major international repatriation from Museums Victoria’s collection.

2023 marked the end of a long road for a unique collection, cared for by Museums Victoria for 144 years.

An ornately embroidered and beaded regalia, created by the Mi’kmaq First Peoples of northeastern Canada, left its home in 1843 in the hands of a public servant.

Over the next decade the collection, including clothing and a pipe, crossed the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, eventually coming to Australia.

And in 1879 it was donated to the museum.

But as the world turned over the next one and a half centuries, the desire to have it returned home to its traditional owners gained momentum.

And now, the regalia—one of only four of its kind known to have survived—has been repatriated to the descendants of those who created it.

‘It’s been a long journey,’ says Heather Stevens, manager of the Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre in Nova Scotia.

‘It has taken so long for someone to come forward, a Mi’kmaw person to push and get this regalia back home.’

A patient campaign

While the repatriation was first requested in 2002, the complexity of the endeavour meant it took more than 20 years to come to fruition.

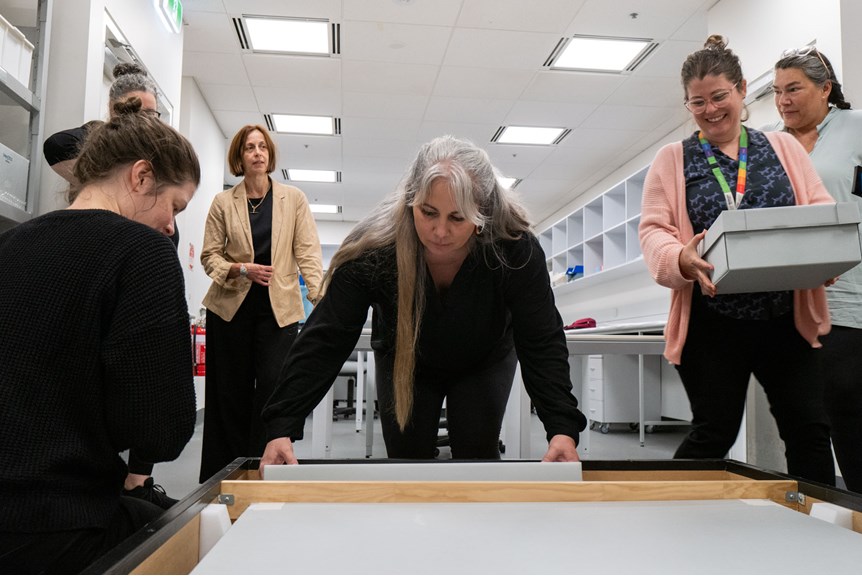

Heather took charge of the effort in 2013, but did not see the regalia in person until making the journey to Melbourne in March 2023.

Gazing upon the coat for the first time at the Melbourne Museum, Heather remarks at the vibrancy of the colours in the fabric and beads that adorn its surface.

‘It was well cared for, there was a lot of thought and love in this,’ she says.

‘It’s so emotional for me because it’s taken so long to see this, and I’m going to bring it home.’

As each of the items is carefully laid out and inspected De-anne Sack, Mi’kmaw pipe carrier and spiritual leader, sings to the garments.

‘Our artisans in Mi'kma'ki, when they work on something like this they put their love, they put their spirits, their good thoughts, good prayers into every stitch, every bead on there,’ says De-anne.

But, as she explains, the oceans between continents have kept those spirits embedded in the regalia and the pipe.

‘So we have that responsibility of bringing all the good spirits back to Mi'kma'ki territory,’ she says.

‘It’s amazing and it is truly and honour, we’re bringing these ancestors home after 160 years.

‘I’m so proud of this, this is literally history for our people,’ De-anne says.

From one side of the world to the other

The Miꞌkmaq are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec, and the northeastern region of Maine.

In 1843 a man named Samuel Douglass Huyghue was employed to survey the line separating New Brunswick, Quebec, and Maine.

It is around this time that he is believed to have either commissioned or purchased the regalia.

‘I know that at the time when this would have been, it was a time when our people were struggling,’ says Heather.

‘Maybe it was something that they had purchased off the women, so the women could feed their family, look after their family.

‘I can’t be angry at that because I don’t know the history as to how it was in his hands and then coming here.’

In 1843 he left Canada, taking the regalia with him, and eventually settled in Australia in 1852.

In December 1854, while a clerk from the Victorian Office of Mines, Huyghue was the first person to document the Eureka uprising on the Ballarat goldfields.

He moved to Melbourne in 1876 and donated his collection, including the Mi’kmaq regalia, to the museum after his retirement.

But it was Huyghue’s notability that placed another hurdle in the repatriation process.

Australian cultural authorities considered Huyghue to be a significant figure in Australian history, so there was a possibility the items were historically significant as they once belonged to him.

Permission to export the regalia finally came through in December 2022.

‘The good thing about our people is that we’re a patient people,’ says De-anne.

Coming home to community

While the original request came from the traditional owners in Canada, the museum also had a desire to repatriate these treasured objects.

‘We’ve been working with Heather to do what was right, actually have them returned back to Country,’ says Dr Shannon Faulkhead, Head of First Peoples Research and Collection at Museums Victoria.

‘Having them here in the collection without the connection, to community, people, country, half its story was missing.’

And she hopes that some of those mysteries, unexplored for most of its history, can be unravelled.

‘Having it back on country they may be able to work out who made it and if they work out who made it maybe they can find the rest of the story,’ she says.

‘Maybe one day we will know if it was gifted or acquired or something different altogether.’

Shannon has led the museum’s efforts to return culturally significant material to traditional owners in Australia and all over the world.

‘Often people talk about collection items in terms of, “It’s ours, we acquired it, it was donated to us”,’ she says.

‘However it got here, if those stories can be uncovered isn’t that going to help people better understand who they are and make the world a little bit better for themselves and their communities?’

And for Heather, this is just the first step.

‘It’s been so dark for our people—not just our people but all first nations people,’ she says.

‘There was so much taken from us and now there is this success where I’m taking it back home people are thinking, “She can do this, maybe I can do it”.

‘This isn’t the last thing that’s going to happen.

‘My ancestors coming with us back home is going to help my people to persevere, to move forward.’

The regalia is now on public display at the Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre in Nova Scotia.