Burlesque dancing and basket weaving: the incredible life of Aunty Veronica Barnett

Snake charming and bikini-clad fire dancing are probably far from most people’s minds when they meet Aunty Veronica Barnett—one of the Melbourne Museum's public faces.

Aunty Veronica is a respected Indigenous Elder who has been a mainstay of the Melbourne Museum, since it opened more than 20 years ago, but her day job is a world away from her past as a burlesque performer.

‘I just love dancing,’ she says with a smile.

It was a love affair that began in her formative years growing up on Bungalow reserve, near Cairns, in northern Queensland.

‘My sister used to play the ukulele wherever she went, she took it everywhere.

‘We entertained ourselves, the whole family did it, except I couldn’t play the ukulele but I loved dancing.

‘Granny Ware used to teach us kids the island dance,’ she says, referencing a community Elder who lived nearby to Veronica and her siblings.

‘My mother was a Torres Strait Islander, but I didn’t know her because she passed away when I was about three years old,’ she says.

Aunty Veronica’s family was evacuated from Thursday Island in 1942, during World War II, and had resettled on the mainland by the time she was born two years later.

Veronica grew up surrounded by a large extended family.

‘Dad was a pearl diver, and a great cook.

‘I was always by the river or the sea and in the rainforest up north.

‘I lived a traditional life until I was 20 years old, when I moved down south,’ she says.

That journey took her first to Sydney, and then to Melbourne.

‘When I came to Melbourne I met Jenny Boyle, a ballet dancer, and a student of Robert Helpmann.

‘She said, “Why don’t you come and do a bit more?”.’

It was that ‘bit more’ that set Veronica on a path to burlesque performing.

‘We made our own costumes and went out and did nightclubs,’ she says.

‘She and I did a number together, a calypso dance, and we would out-dance each other.

‘She was white and I was black, but it was a good combination and we were friends.

‘And this one particular time she started dancing and I took a step forward ready to do my bit and I stood on her skirt, and her skirt came off,’ laughs Veronica.

‘The look on her face, we couldn’t help but laugh.

‘The (nightclub) owner goes, “I like that bit”, and I said “That was an accident!”.

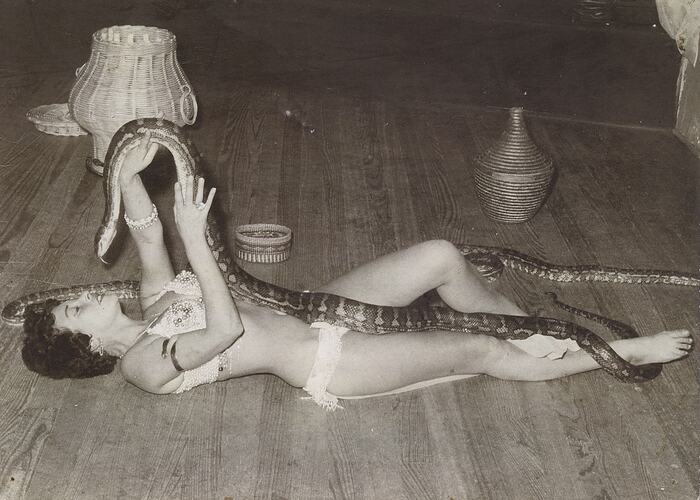

‘So I started there and then worked on a routine of my own, dancing with snake and fire.

‘I’d dance with the snake first, put the snake down then light the fire up,’ she says.

Aunty Veronica would run two burning sticks along her arms, belly and legs as she danced, and end the performance with a thrilling display of fire eating.

‘I have a scar on my leg as proof,’ she says.

Veronica had been exposed to reptile handling as a child and sought out Brian Barnett, a herpetologist in Melbourne.

‘When I met him I bought a carpet snake and an amethystine (scrub python)…and he just sort of hung around,’ she says.

Not everyone was impressed by Veronica’s snake routine though.

‘Bernice Kopple, she was Scottish…she had a snake too,’ says Veronica.

‘She didn’t like it because I was competition…but I explained, “Your dance is completely different to mine, you’re an Egyptian belly dancer, but I’m using fire and snake”.’

‘We became best of friends.

‘I got married and she went her own way…but her bra is up in the collection.’

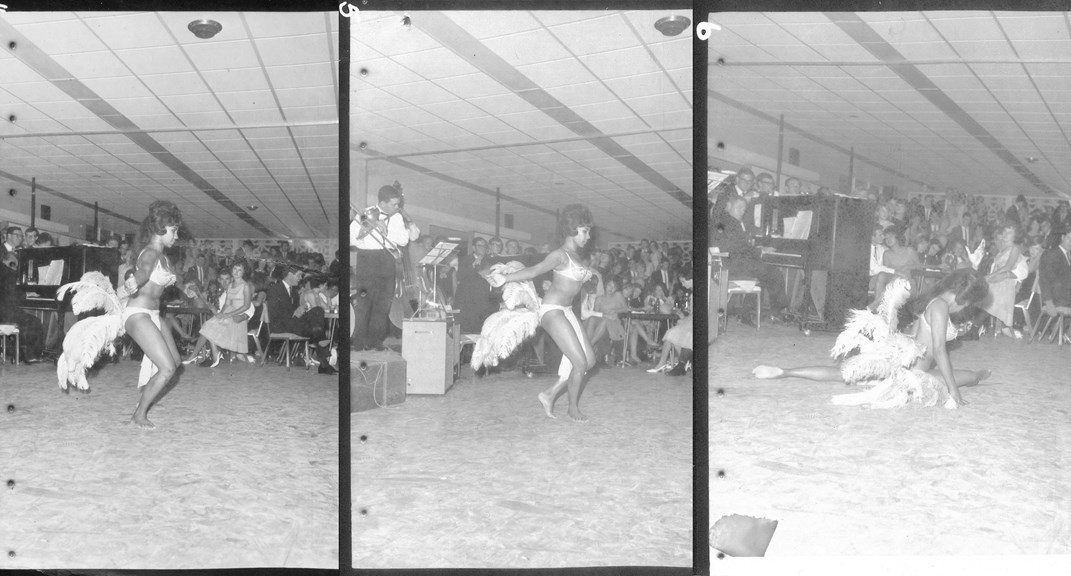

Veronica wowed crowds in nightclubs, hotels, RSL clubs and universities in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne during the 1960s.

She was the opening act for Johnny Devlin and the Strangers in Brisbane: ‘One of them told me, “You’re a hard act to follow”,’ recalls Veronica.

On a trip back up north for a holiday in Mossman, Veronica was asked to perform for a charity event one windy night.

‘I got out there and they had fish nets strung up as the background and I said, “You got a fire extinguisher, just in case?”.

‘Time came I started dancing with the snake and the fire and as I swung, a bit of fire caught the net.

‘They though it was part of the act and I’m dancing around and as I got close enough I said, “Put the fire out!”,’ she laughs.

‘They did in the end, but they enjoyed it—it was something different.’

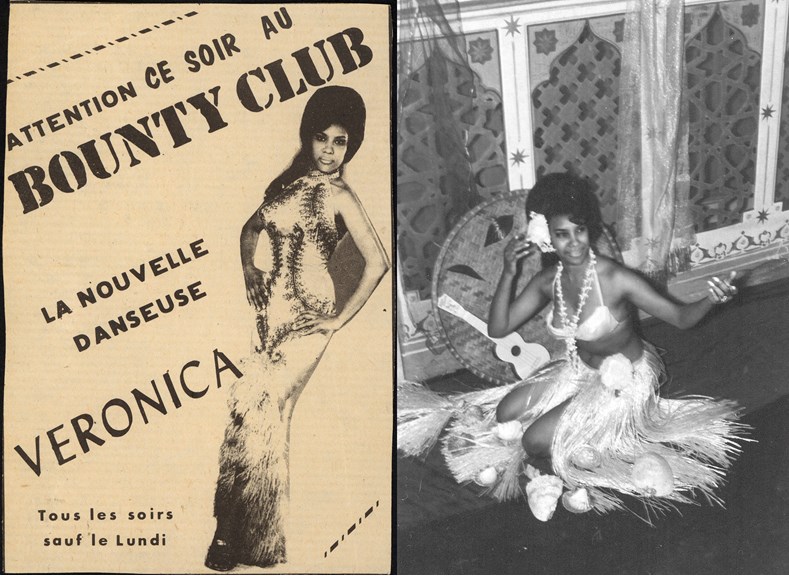

Veronica’s dancing also took her to Tahiti.

‘I went over there for two weeks to dance at Le Bounty Club and ended up staying there six weeks—they liked my act so much that they asked me to stay on.

‘I came back, ended up getting married to Brian,’ she says.

‘A few years after I got married, when I had my first son…I just stopped dancing.’

Aunty Veronica stepped away from the limelight to raise her two children and started exploring new pursuits.

Veronica helped her husband set up the Victorian Herpetological Society, and they took reptiles to public exhibitions and shows across Melbourne.

Aunty Veronica joined the Melbourne Museum as a customer service officer, ahead of its opening in October 2000.

Since then, she has guided countless visitors through the Milarri Garden at the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre and Forest Gallery, teaching them about sustainability, plants and animals.

‘When you take from mother earth you must give back, so the next generation doesn’t miss out.’

Part of that knowledge is Aunty Veronica’s skill in weaving, which she has generously shared with staff and museum visitors alike.

‘My dad taught me to weave up north but I didn’t take much notice when I was a kid, until I came down here and I thought I can do that—that’s how it all started.

‘I’ve got something here that I can pass onto the next generation, regardless of who you are,’ says Veronica.

‘Sharing Indigenous knowledge is important to me—I feel the need to pass on knowledge, so it’s never lost.’