Jurassic relict: a new family of Brittle Stars

By Dr Tim O'Hara

Long-armed and bristling with teeth, this Brittle Star is a marine relict from the Jurassic era discovered on a remote seamount.

Let me introduce you to Ophiojura, a new species of Brittle Star.

My colleagues and I have described this new deep-sea creature in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

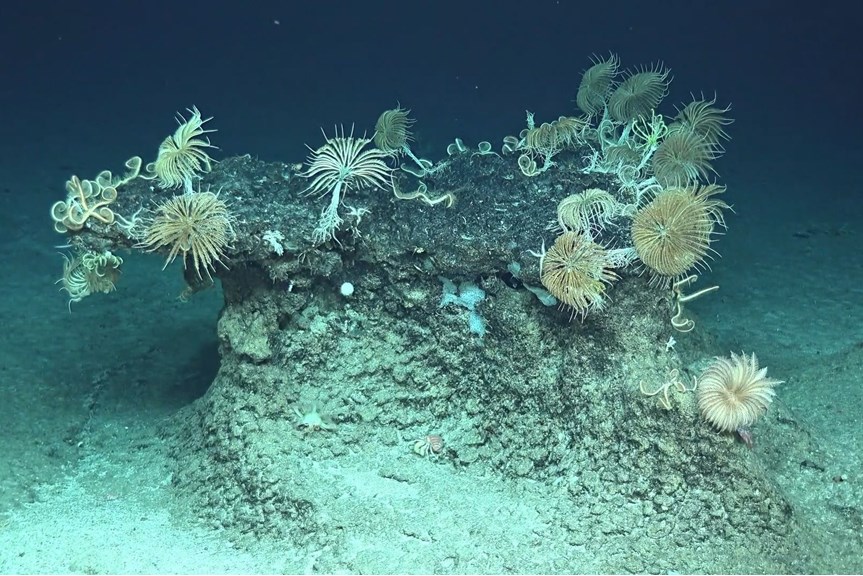

Scientists from the French natural history museum found it 500 metres below the ocean’s surface on the summit of a secluded seamount called Banc Durand, 200 km east of New Caledonia.

Brittle Stars are a group of unfamiliar animals with radiating arms, remotely related to starfish, which occur on seafloors around the globe.

Being an expert in deep-sea animals, I knew at a glance that this one was special.

The eight long arms armed with rows of hooks and spines — and the teeth!

A micro CT-scan revealed bristling rows of sharp teeth lining every jaw, which I reckon are used to snare and shred its prey.

It is one of a kind.

The last species of an ancient lineage, like the Coelacanth fish (Coelacanthiformes) or the Tuatara (Sphenodon).

DNA evidence shows that Ophiojura evolved from nearest living relatives approximately 180 million years ago.

This is way back in the Triassic to early Jurassic, when dinosaurs were just getting going.

What is amazing is that we have found small fossil bones that look similar to our new species in Jurassic rocks from northern France.

Scientists used to call animals like Ophiojura ‘living fossils’ but this isn’t quite right because life doesn’t become fossilised like that.

The ancestors of Ophiojura would have continued to evolve in subtle ways over the last 180 million years.

We now call them palaeo-endemics — meaning a formerly widespread branch of life that is now restricted to a few small areas.

For seafloor life, the centre of palaeo-endemism is on continental margins and seamounts in tropical waters between 200 and 1000 metres deep.

This is where the relicts of ancient marine life are to be found.

Like ‘rainforests of the sea’, the tropics support the most diverse marine habitats on the planet.

Seamounts, like the one Ophiojura was found on, are usually submerged volcanos that were born millions of years ago.

Lava oozes or belches from vents in the seafloor, continually adding layers of basalt rock to the volcano summit like layers of icing on a cake.

The volcano can eventually rise above the sea surface, forming an island volcano like in Hawaii.

Coral reefs can form around the island shoreline.

But eventually the volcano dies, the rock chills, and the heavy basalt causes the seamount to sink into the relatively soft oceanic crust.

Given enough time, the seamount will subside hundreds or even thousands of metres below sea-level and gradually become covered again in a deep-sea fauna.

Its sunlit past is remembered in rock as a layer of fossilised reef animals around the summit.

While our new species is from the southwest Pacific, seamounts occur worldwide and we are just beginning to explore those in other oceans.

In July-August 2021, I will lead a 45-day voyage of exploration on Australia’s oceanic research vessel, the RV Investigator, to seamounts around Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the eastern Indian Ocean.

These seamounts are ancient — up to 100 million years old — and are almost totally unexplored.

We are truly excited at what we may find.

Seamounts are special places in the deep-sea world.

Currents swirl around them, bringing nutrients from the depths or trapping plankton from above, which feeds the growth of spectacular fan corals, sea whips, and glass sponges.

These in turn host numerous other deep-sea animals.

But these seamount communities are vulnerable to human activities like deep-sea trawling and mining for precious minerals.

The Australian government has recently announced a process to create massive new marine parks in the Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) regions.

Our voyage will provide the critical data required to manage these parks into the future.

The New Caledonian Government has also created a huge marine park in offshore areas around their islands, including the Durand seamount.

These marine parks are beacons of progress in the global drive for better environmental stewardship of our oceans.

This article was first published on The Conversation.