How poo shapes a city (and other scatalogical stories)

What do Melbourne’s laneways, the Spotswood Pumping Station at Scienceworks, and termite mounds all have in common?

Melbourne’s CBD is well known for its network of laneways and alleys, full of street art and hidden bars and restaurants.

But who do we have to thank for these crisscrossing delights?

It turns out that it might be due to something that a lot of us don’t like to think about—toilets.

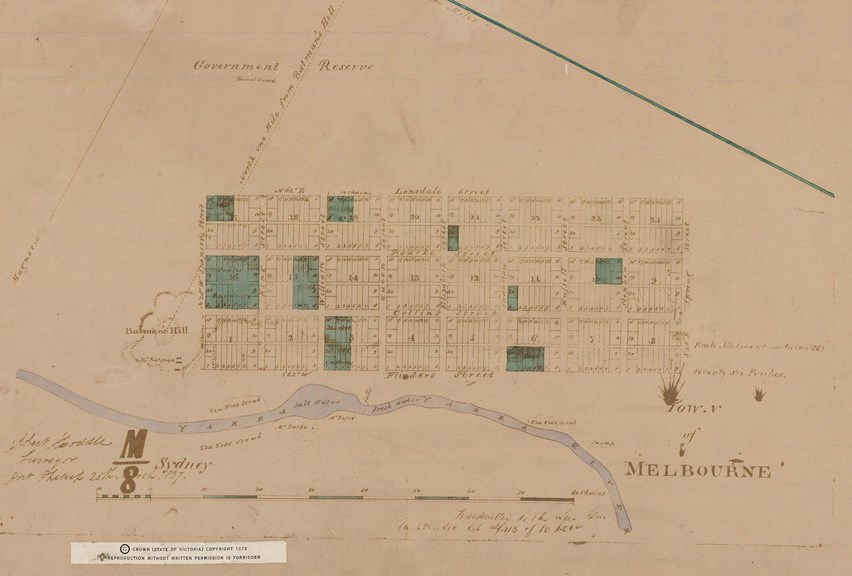

The Melbourne city grid was designed in 1837 by Robert Hoddle, a surveyor who worked under Governor Richard Bourke.

Hoddle designed the grid so that each building sat on a major street but could also be accessed from the rear via another, smaller street or lane.

This was vitally important as the entire city was originally built without a sewerage system.

Initially these lanes were mostly hidden from the public eye and used to access the ‘cesspits’—typically a hole in the ground lined with bricks.

Once these pits were full, it was the responsibility of the resident or business owner to transport the contents to a mass collecting point.

This system left a lot to be desired, as people would often empty their pits directly onto the streets to save the effort of transporting the contents across town.

It also led to the city being labelled ‘Smellbourne’ by visitors.

And it wasn’t just the smell that you had to worry about, the piles of poo everywhere were making people sick with diseases like typhoid and cholera.

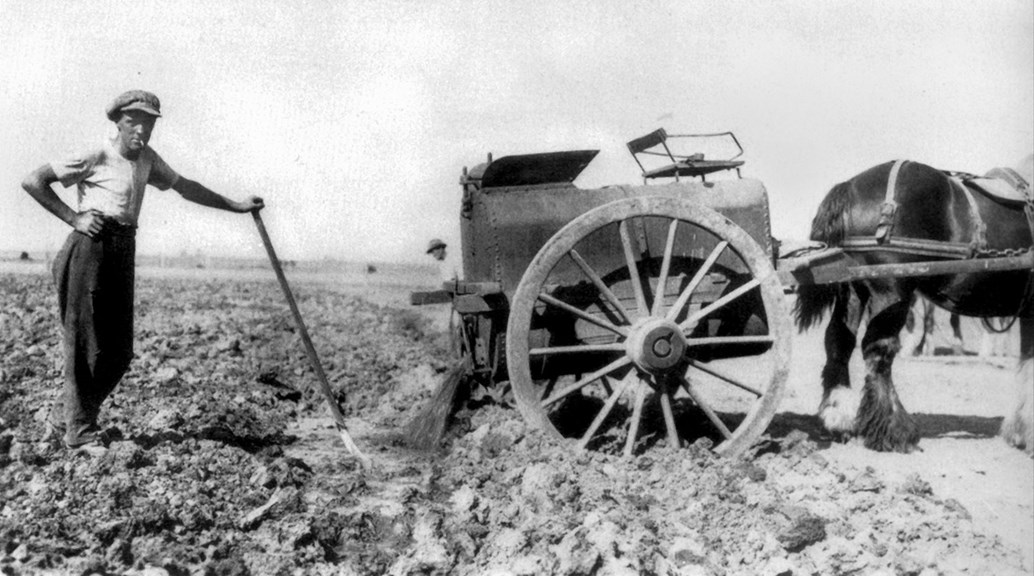

In the 1860s the Melbourne City Council began the process of switching to a cleaner, more organised process.

Residents were instructed to do away with their cesspits, and use sanitary pans.

These pans were much shallower, but more accessible.

The city council employed a team of ‘nightmen’ to collect this waste, or ‘nightsoil’, once a week by traveling up and down the system of alleyways.

While this newer system improved the situation somewhat, human waste was still ending up on the streets and making people sick.

Big changes were needed.

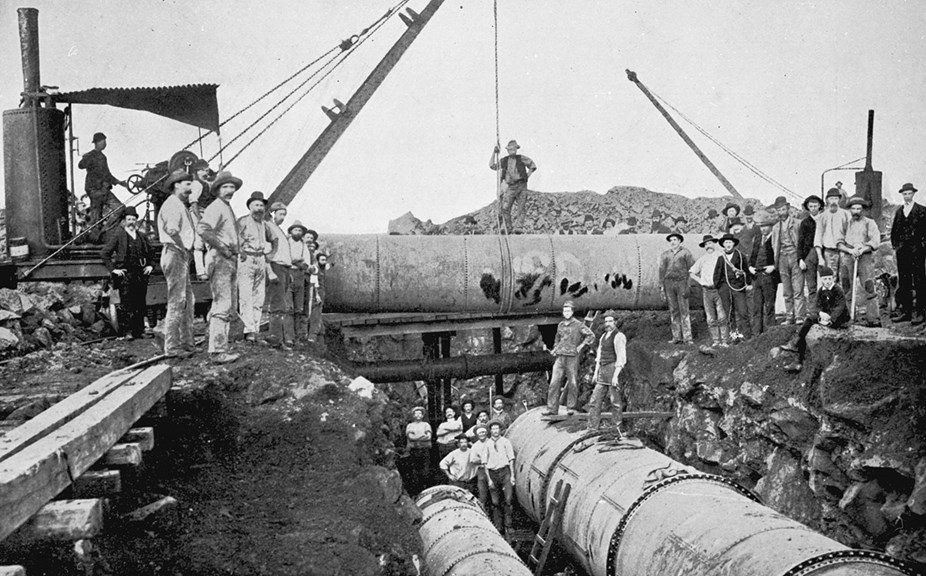

In 1888 a Royal Commission into Public Health recommended the creation of Melbourne’s first sewerage system.

Throughout the 1890s massive works were undertaken to complete the sewerage network, along with the Werribee Treatment Plant and the Spotswood Pumping Station.

With the treatment plant so far away from the city, the pumping station was an important piece of infrastructure that pushed the waste 3.5 kilometres on its uphill journey westward.

In 1897 homes around Melbourne began connecting their toilets to the newly created sewerage system and the need for the city’s network of alleyways began to dwindle.

But these laneways wouldn’t be forgotten.

Over the next 125 years they would be repurposed into shopfronts, arcades and delivery entrances that make up the city as it is today.

Humans aren’t the only animals who build their cities around poo

At Museums Victoria our experts at Ask Us are regularly asked about poo in the animal world.

One Australian insect goes a step further than building a poo-friendly city—it actually uses its own waste to build very large and intricate structures.

There are around 300 species of termite in Australia, and almost all of them build their homes out of ‘carton’, which is a polite name for poo mixed with wood fragments.

Carton sets almost like a plaster and can be incredibly strong.

It is often used by termites to line the inside of tunnels bored through soil and wood to prevent cave-ins.

Without this incredible poo-based building material, termites wouldn’t be able to build the iconic mounds that feature all over the outback landscape.

Many other insects use animals’ poo as an important part of their lives, with various species of flies and beetles feeding exclusively off the waste of other animals.

Larger animals, particularly herbivores, tend to have less efficient digestive systems, meaning that there’s still lots of nutrients left in the waste they excrete.

Some insects like the Dung Beetle take advantage of this inefficiency and build large balls of other animals’ poo, which they then lay their eggs inside.

This ensures that the hatching larvae has a safe and secure food source once it hatches—a sort of poo-nursery.

Not to be outdone by the insect kingdom, some native Australian mammals have been observed using their poo as building blocks on a smaller scale.

Wombats pile their waste into little pyramid structures, which is made easier by the fact that their poo is cube shaped.

These cube shaped poops are made possible by a special biological feature of the wombat.

Two large muscles, one horizontal and one vertical, both contract around the final section of the large intestine, squeezing the contents from top, bottom and the sides.

This doesn’t just achieve perfectly proportioned poo—it also serves to squeeze as much water out of the waste as possible, a valuable trait when you live in a country as dry as Australia.

Keen to know more about how Melbourne was saved from being ‘Smellbourne’? Read on.