Celebrating 170 years of Museums Victoria

As we celebrate our 170th anniversary, explore some of our favourite collections and objects from the Museums Victoria State Collection.

170 years ago, what is now Australia’s largest public museum organisation began in a small office in Melbourne.

Since 1854, the State Collection has grown to 15 million objects that represent the story of life on planet Earth.

It is a collection that continues to inspire and entertain visitors from across the world, so what better way to celebrate such a significant milestone than highlighting some of these collection objects from the last 17 decades.

1850s: The first specimen donated to the collection

When the museum was first getting started out of the Government Assay Office in La Trobe Street in 1854, its founding director Sir Frederick McCoy was keen to build up a collection of natural specimens.

And this taxidermy mount of a Little Pied Cormorant (seen on the left), presented by Drew Esq, was noted by The Argus as, ‘the first donation to the museum.’

It is also mounted alongside another Little Pied Cormorant from William Blandowski’s expedition to the Murray in 1857, which provided invaluable specimens to the museum’s fledgling collection.

Another find from this expedition—an Australian native mouse, named after the famed naturalist John Gould—was the last record of the animal before genetic analysis in 2021 revealed the species had survived on a remote island in Western Australia.

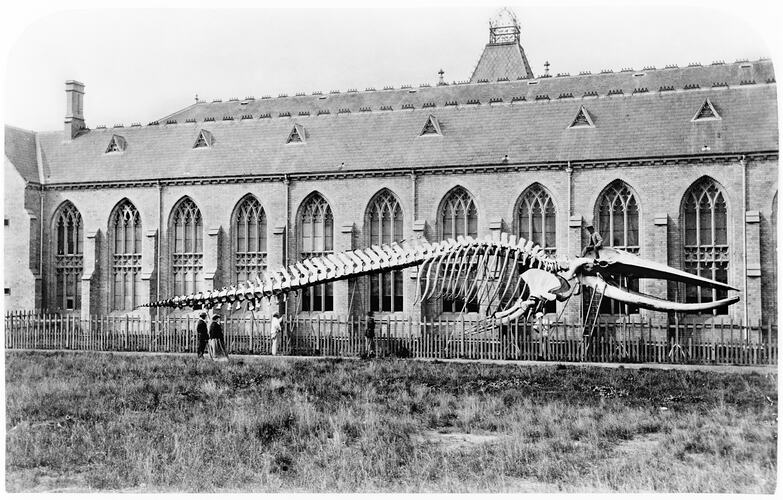

1860s: Our first whale skeleton

After outgrowing the Assay Office, the museum’s second home was at the University of Melbourne campus where it first displayed a whale skeleton.

This skeleton probably belonged to a Blue Whale—the largest species of these oceanic giants.

In 1867 Frederick McCoy originally described this skeleton as a new species, Physalus grayi.

But this name was preceded by earlier scientific names given to the same species of whale, so the name is not used today.

Unfortunately, because the skeleton was displayed outside and subject to the elements all that remains of this specimen today is some baleen.

But you can still see a skeleton of a Blue Whale in the foyer of Melbourne Museum today.

1870s: The Prodromus Collection

This is the most scientifically significant art collection from 19th century Victoria.

The Prodromus Collection was an ambitious project started by McCoy, who sought to describe all Victorian native animals—except for birds which had already been covered by John Gould.

Published between 1878 and 1890, it was such a large undertaking that McCoy didn’t live to see its completion.

The collection contains descriptions of 447 species and includes more than 1000 individual illustrations which captured the creatures and their environments—many of which are now lost—in such detail they are still relevant today.

And you can view every page on the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

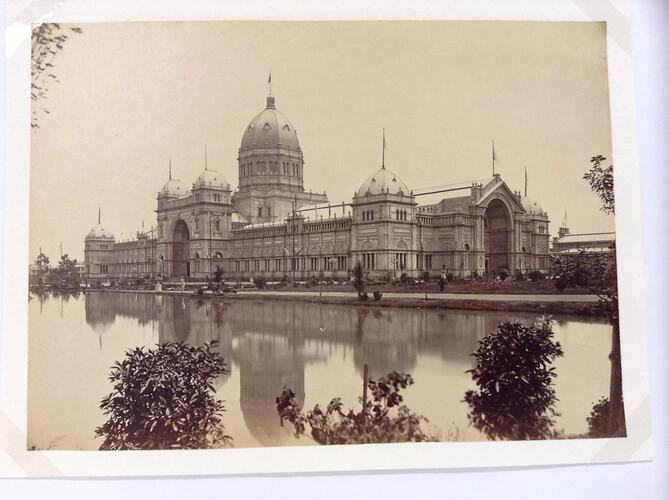

1880s: Our biggest thing

Technically the Royal Exhibition Building is not an object in the State Collection, but it is the biggest item under Museums Victoria’s care, so it is hard to overlook.

In the late 19th century Melbourne was still basking in its riches from the gold rush, and this building is a product of that prosperity.

Designed by Joseph Reed and completed in time for the 1880 International Exhibition, this building is the only surviving Great Hall from a major industrial exhibition of the time.

It has also served a multitude of purposes over the years, including as a barracks, migrant reception centre, federal parliament and vaccination hub.

2024 also marks the 20th anniversary of the Royal Exhibition Building’s entry to UNESCO’s World Heritage list.

1890s: Registration number 00001

Because the State Collection covers such a wide remit, from scientific samples to historically significant objects, you’ll find several different designations depending on the type of item or material.

In this case ST00001 is the first specimen registered in the science and technology collection.

The silkworms which made these cocoons were reared in the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn, using imported eggs from India.

The cocoons were donated to the museum in 1895.

This was also the decade that the collections were moved from the Melbourne University site to join those of the Industrial and Technological Museum on Swanston Street, at the rear of the State Library of Victoria.

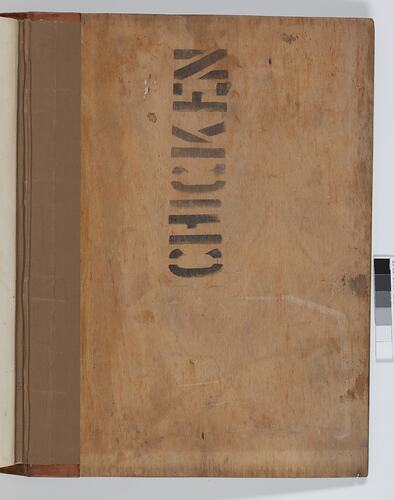

1900s: First Antarctic publishing

By the 1900s most continents already had established printing operations, but this is the first book ever published in Antarctica.

And it only happened because members of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition borrowed a printing press to take with them.

The Aurora Australis is a collection of prose and poetry written by the crew, with a preface by Shackleton who also edited the volume.

Published between 1908 and 1909, there were only about 100 copies ever produced and they all vary slightly due to the difficult conditions and inexperience of the printers.

Ours still carries the ‘chicken’ label from the original food packing case that was used to bind the book.

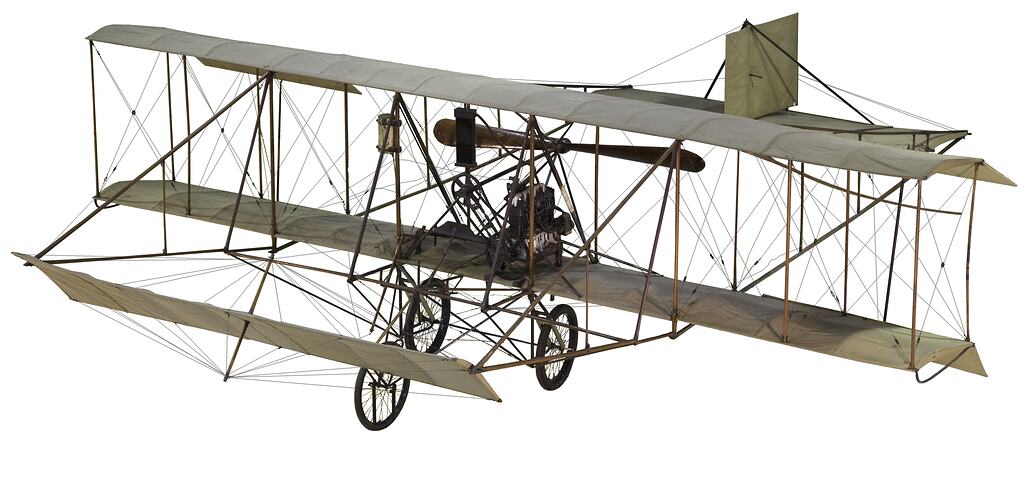

1910s: Australia’s first aeroplane

This was the first Australian designed and built aeroplane to achieve controlled, powered flight.

A 28-year-old John Duigan designed and constructed the aircraft with his brother Reginald at their family farm at Mia Mia, in country Victoria.

What’s remarkable is that Duigan had never seen or flown an aircraft before.

His first design was a glider based on a postcard photograph of the Wright Brothers’ Flyer, which he ‘flew’ in strong winds by tethering it to the ground with 110 metres of fencing wire.

The biplane followed and made its first flight in 1910.

1920s: A giant of early whale evolution

In 1921, a palaeontologist named Francis Cudmore was walking along the banks of the Murray River, in South Australia, when he noticed a fossil protruding from the sandstone.

He collected as much as he could and gave the fossils to the museum, where they sat for more than 100 years before anyone realised their significance.

The fossils belonged to a nine metre long baleen whale, that lived 19 million years ago—a giant whale for its time.

In 2023, researchers used these fossils to overturn the previous understanding of whale evolution, by proving they first got big in the southern hemisphere.

1930s: Phar Lap

Still one of the museum’s most popular attractions, Phar Lap is Australia’s most famous racehorse.

Born in 1926, Phar Lap was moulded into a champion by Sydney trainer Harry Telford and won 37 races from 51 starts.

He won almost every major Australian race, many of them twice.

But as much as Phar Lap is revered for his performance on the track, he is just as well known for the mystery surrounding his death in America in 1932—which was later found to be from arsenic poisoning.

And while the museum is known as Phar Lap’s home, we only have his taxidermy mount in the collection.

Phar Lap’s heart resides in the National Museum of Australia, in Canberra; his skeleton is in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the country of his birth.

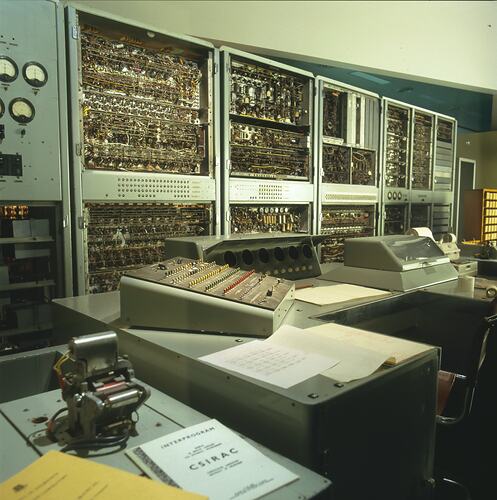

1940s: The first computer in Australia

CSIRAC was the first stored-memory electronic computer in Australia, just the fourth in the world, and the first one to generate music.

Designed in 1947, the computer ran its first program two years later and was in full operation by 1951.

While computing has evolved considerably since, in its day CSIRAC was able to operate more than 1000 times faster than the best mechanical calculators.

It made a pioneering contribution to software development and computer training.

It was donated to the Institute of Applied Science of Victoria (now part of Museums Victoria) in 1965 and is today the world's only complete surviving first-generation digital electronic stored-memory computer.

You’ll find it on display at Scienceworks.

1950s: A remnant of Australia’s nuclear tests

This glass is a remnant of the nuclear bombs tested in Australia.

The United States tested and used the first nuclear weapons in the 1940s during World War II, and other countries were keen to develop their own.

The British Government detonated nine nuclear bombs during tests in outback South Australia, starting in the 1950s.

Most of those were at Maralinga, which is where this sample of atomic glass in the museum’s collection comes from.

Nuclear bomb tests all around the world exposed the people and the environment to dangerous levels of radiation.

But while this glass was created by these explosions, it remains only mildly radioactive today.

1960s: Understanding the origins of the universe

This meteorite burst into the atmosphere above Murchison, in northern Victoria, on 28 September, 1969.

And, as we later discovered, it contains some truly astounding discoveries.

It is seven billion years old, and contains pre-solar grains that formed in supernovas long before our own sun appeared.

Fragments of this meteorite have enabled us to learn about how our own, and other, solar systems formed.

Fragments were found across an area of 35km² and ended up all over the world—including the Field Museum in Chicago, which has nearly 52kg of it.

The museum has about 3.5kg, some of which is on display in Dynamic Earth at Melbourne Museum.

[lecture video https://youtube.com/live/korU7i71bmc]

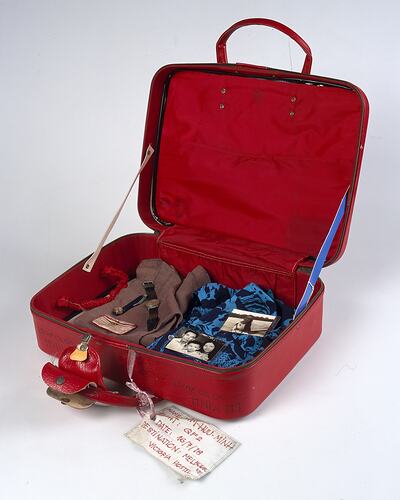

1970s: Finding refuge

This red suitcase from the collection was used by Vietnamese refugee Cuc Lam on her journey to Melbourne in 1978.

Cuc and her husband, Minh, escaped from Vietnam in a river boat, which was picked up in international waters by a Malaysian ship eight days after their escape.

What little possessions they were able to take with them, were in this case.

They spent five weeks in a refugee camp in Malaysia before being accepted as refugees by Australia.

The suitcase was donated to the museum by Cuc herself in 2001, along with several other personal objects.

The collection is a rare glimpse into the refugee experience and represents a pivotal time of change in Australia’s multicultural policies.

1980s: An electric van

While electric vehicles are commonplace these days, serious efforts to make them mainstream began decades ago.

This Lucas Bedford electric van is one of those attempts, spurred on by the 1970s oil crisis.

Four of these vehicles came to Australia, where they were trialled on public roads and used in major events like the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games.

Limited range and speed meant they never took off, but this van remains in the collection as an important step in the evolution of electric vehicles.

This was also a pivotal decade for the museum itself, as several of the state’s separate museums were merged to form the Museum of Victoria, creating Australia's largest and most diverse scientific and cultural organisation.

1990s: An iconic statement

This is the St Kilda Football Club jumper worn by Nicky Winmar, during his celebrated stand against racism in sport on April 17, 1993.

Winmar was subjected to a tirade of racial abuse by the Collingwood Cheer Squad, particularly during victory celebrations.

His reaction was to lift his jumper, and point at his skin, uttering ‘I’m black and I'm proud.’

After being stored in a cupboard, as a personal souvenir of a memorable day, Winmar traded the jumper in 1994 with American basketball player Tim O'Brien.

O'Brien took the jumper back to his home city of Texas and hung it on the wall, along with numerous other sporting uniform pieces from around the world, obtained through similar exchanges.

He offered the jumper to the museum in 2012, where it is now on display at the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre.

2000s: Melbourne’s biggest family album

The museum has embarked on several community collection projects over the decades, but this is among our favourites as it is so close to home.

Melbourne's Biggest Family Album project began in 2006, encouraging former and current Melburnians to submit their favourite photographs that document life in the city.

The result was more than 1000 photos, some of which date back to the late 19th century, which offer a previously unseen perspective of Melbourne’s history.

You’ll find some of these images on display in The Melbourne Story.

Melbourne’s Biggest Family Album was based on another innovative project, The Biggest Family Album in Australia, undertaken by the museum in the 1980s and 1990s.

2010s: Biobank beginnings

The tissue and DNA collection, overseen by our Senior Manager of Genetic Resources, Dr Joanna Sumner, is one of the largest and most diverse in Australia and is a central research facility for the work of the Museums Victoria Research Institute.

The museum started collecting and freezing genetic material for research purposes in the 1980s, but with the 2016 opening of the Ian Potter Australian Wildlife Biobank at Melbourne Museum, it was able to greatly expand the collection capacity and scope.

This state-of-the-art facility stores genetic material from close to 50,000 samples including over 2600 species, in liquid nitrogen at -185°C, preserving them indefinitely.

This facility is now growing and preserving living cells, such as sperm and primary cell lines, from native wildlife, unlocking further possibilities for the preservation of endangered native animals, like the Smoky Mouse and the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon.

2020s: A Triceratops comes to town

Last, but by no means least, is our Triceratops which arrived at Melbourne Museum in 2021.

Triceratops horridus is an icon of the dinosaur age and lived about 67 million years ago.

What is remarkable about this fossil is that is one of the most complete Triceratops skeletons in the world—about 85 per cent complete.

It was discovered in Montana in 2014 when part of the pelvis was spotted protruding from the surrounding sandstone.

Since arriving at the museum Horridus has been visited by more than a million people.

So, there you have it—170 years of the museum.

Happy anniversary Museums Victoria, and who knows what wonders will be added to the collections over the next 170 years?