These pieces of atomic glass are the remnants of the first nuclear bombs

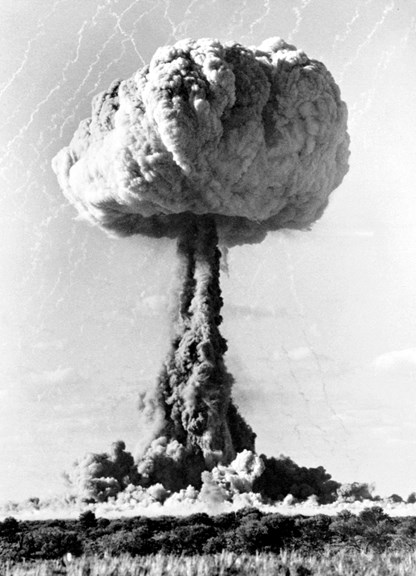

Forged in the fury of nuclear explosions, like Oppenheimer’s Trinity test and British bombs at Maralinga, atomic glass is more than a curio in museum collections.

The first nuclear bomb detonation on 16 July 1945 forever changed the world.

Not only did the test, overseen by J Robert Oppenheimer, impart humanity with the knowledge that we now had the means to destroy ourselves, but it also left us with an unintended new material—atomic glass.

When a sphere of detonated TNT compressed the plutonium core, it was simultaneously bombarded with neutrons that split some of its atoms, sparking a nuclear chain reaction that resulted in a colossal explosion.

The blast melted the bomb’s support structure and wiring, and sand and debris from the surrounding area.

And, after the fury of the explosion had died away, the desert floor became littered with a strange green glass.

This material was named trinitite, after the Trinity site where the first bomb was detonated in the state of New Mexico in the USA.

‘It is very slightly radioactive,’ says Oskar Lindenmayer, who manages Museums Victoria’s geosciences collection.

‘It’s only just above background radiation,’ says Oskar, referring to the ordinary levels of ionising radiation in the environment.

‘In fact, compared to some of the other materials that I work with in the collection it’s really not that radioactive.’

Nevertheless, Oskar still wears rubber gloves while handling the trinitite samples from the museum’s collection.

‘One of the main radiation types is alpha radiation—that’s the most damaging kind of radiation—but it’s not going to penetrate these gloves.’

While it is now illegal to take the atomic glass from the Trinity site, it has become a sought-after souvenir for collectors.

‘It’s like having a piece of history…it’s an object that draws you to a time and place,’ says Oskar.

‘You’ve got a physical object that can’t be replicated, no copy is going to give you the same feeling as having a piece of glass that was at the first nuclear bomb test that was a defining moment in human history.

‘It really marks a fundamental change in the way we were interacting with the world around us—having a greater mastery over it but also exposing ourselves to the risks that go along with that.

‘These are hugely powerful forces that humans have been able to meddle with,’ he says.

The Trinity test paved the way for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended World War II.

But once the technology was let loose on the world, other nations were quick to set up their own nuclear weapons programs.

Australian nuclear tests

The British Government detonated nine nuclear bombs during tests in outback South Australia, starting in the 1950s.

Most of those were at Maralinga, which is where another sample of atomic glass in the museum’s collection comes from.

‘If you look at this piece of glass from the Maralinga test site, it looks glassy and shiny, it’s got a frothy layer at the top full of gas bubbles that would have been trapped when that glass solidified.

‘On the bottom it’s got a sandy layer which will have been bits of sand in the area that have adhered to the bottom of this glass.’

Like trinitite, the glass from Maralinga has a green tinge to its surface—a colour that most likely comes from iron.

‘What’s going on when you’ve got these nuclear bomb test happening is you’re reaching potentially millions of degrees Celsius and that’s well and truly more than enough to produce glass—we produce it at less than 2,500 degrees industrially,’ explains Oskar.

‘Glass, geologically, forms when you’ve got molten material that is cooling so quickly that crystals don’t have time to form.

‘That results in the atoms that make up the glass being arranged in a random order, and you get a material that is actually fairly unstable.’

Atomic glass may be a by-product of these explosions, but it is also a record of a controversial time in world history.

Nuclear bomb tests all around the world exposed the people and the environment to dangerous levels of radiation, and not just those in the immediate area.

Even those thousands of kilometres away could be affected by radioactive particles, that had been blown into the upper atmosphere, falling back to earth.

The United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union agreed to ‘put an end to the contamination of man's environment by radioactive substances,’ by banning nuclear weapons testing in 1963.

‘We have this material link to these historical events,’ says Oskar.

‘It’s by having items like this in the collection that we can better understand the history and also have a lens through which to tell people about the history.’