Discovery of 24 dinosaur tracks reveal polar dinosaurs once roamed

Polar dinosaur footprints leave new clues to life in Early Cretaceous

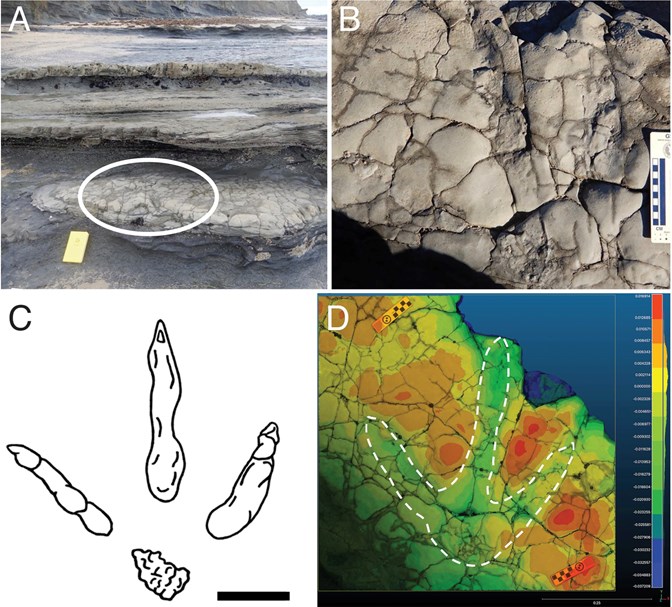

Researchers have discovered 24 dinosaur tracks on Boonwurrung Country on the Bass Coast of Victoria, dating back to the Early Cretaceous when Australia was still connected to Antarctica.

Published today in the Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, the discovery indicates that large theropod dinosaurs thrived in this polar environment, prowling the river floodplains when the ice thawed during the summers.

Found in the Wonthaggi Formation and made between 120 and 128 million years ago, the tracks include 18 theropod tracks and four tracks made by ornithopods – small, herbivorous dinosaurs that may have been prey for the theropods.

Dr Anthony Martin, a geologist and palaeontologist from Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia) spearheaded the international team of researchers including Dr Thomas Rich, senior curator of vertebrate palaeontology at Museums Victoria Research Institute, and Dr Patricia Vickers-Rich, Professor Emerita of palaeontology at Monash University.

‘The discovery of numerous theropod tracks in the Cretaceous rocks of Victoria is the best evidence to date that these former polar environments supported a variety of dinosaurs, including large carnivores that most likely preyed on smaller dinosaurs, fish and turtles,’ says Dr Rich.

‘Dinosaurs are more common at the site than we previously realised. The tracks are preserved in floodplains next to channel sandstones, suggesting that dinosaurs travelled through the landscape during polar summers, following flooding after the spring thaw,’ notes Professor Vickers-Rich.

Of the 24 tracks reported in the paper, two are of uncertain origin and 18 are theropod tracks ranging in length from 18 centimetres to 47 centimetres. They are distinguished by relatively thin toes tipped with sharp claws. Four tracks were made by ornithopods – the first reported from the Wonthaggi Formation – and range in size from 10 centimetres to 18 centimetres.

The range in sizes of the tracks suggests a mix of juvenile and adult ornithopods and theropods. ‘That indicates that these dinosaurs may have nested and raised their young in the polar environment,’ Professor Martin notes.

Dr Thomas Rich and Dr Patricia Vickers-Rich have led a major effort since the 1970s to uncover fossils in Victoria, known as the Dinosaur Dreaming Project.

Co-author and local Dinosaur Dreaming volunteer fossil hunter Melissa Lowery played a pivotal role in the latest discovery. Known for her incredible eye that allows her to pick out distinctive patterns from surrounding materials, Lowery is known as ‘the doyenne of dinosaur discovery’ for her hundreds of finds. The tracks she discovered for the current paper were likely made when the dinosaurs were walking on wet sand or mud in the floodplain.

Victoria’s rocky coastal strata mark where the ancient supercontinent Gondwana began to break up around 100 million years ago, separating Australia from Antarctica. The Wonthaggi Formation offers a glimpse into the polar environment at that time, with a rift valley and braided rivers. Although the mean annual air temperature was higher during the Cretaceous than today, during the polar winters the ecosystems experienced deep freezing temperatures and months of darkness.

Today the Wonthaggi Formation is a fossil-rich site yielding one of the best assemblages of polar dinosaur body fossils in the Southern Hemisphere.

‘Were the dinosaurs living in this environment during the winter? We don’t know,’ Martin says. ‘It would have been frozen over and dinosaurs walking on ice don’t leave tracks.’

John Broomfield, manager of photography and imaging at Museums Victoria, produced 3D digital images of the tracks to further help with data analyses.

Peter Swinkels, former preparator at Museums Victoria Research Institute, preserved the track specimens by going into the field to make moldings and casts.

Doris Seegets-Villiers, a paleontologist at Swinburne University of Technology in Victoria, helped with data collection and mapping of the tracks in the field.

The current paper follows on the heels of the authors’ 2023 findings of 27 bird tracks from the Early Cretaceous found at the same site — the oldest-known evidence for birds so far south.

Read more about the research on the Museum Victoria website