Why are there so many whale skeletons in museums?

Whales grace the halls of many a natural history museum, but they are there for more than just show.

Step into any natural history museum around the world and there’s a good chance you’ll find a whale skeleton.

The Melbourne Museum is no exception, giving visitors the opportunity to walk alongside an 18.7-metre-long Blue Whale specimen in the main hallway.

But have you ever wondered why it is almost always whales?

‘The whale skeleton is the icon of the natural history museum, along with the dinosaur,’ says Kate Phillips, senior curator of science exhibitions at Museums Victoria.

If you had to choose a symbol to identify a building as a natural history museum, a whale skeleton is a safe bet.

And there is a good reason for their prevalence—they inspire awe.

‘The fact that Blue Whales are the largest creature alive today is one of the reasons they are so popular.

‘Ours is a Pygmy Blue Whale, so it’s not even as big as they can grow!’

But there is a lot more to whale skeletons than their ability to make our jaws drop.

By popular demand

Whales represent one of the most remarkable parts of the natural world.

Museums Victoria’s senior curator of vertebrate palaeontology, Dr Erich Fitzgerald, has spent much of his career studying them.

‘They represent the superlative in nature as one extreme of what is biological possible,’ he says.

‘These seem almost impossible, mythic animals, yet they are real.’

The majestic mammals feature in The Bible, creation stories—including the Dreamtime story of Buriburi and the Maori tradition of the whale rider—and classic literature, such as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, inspired by the writer’s time as a whaler.

Back in the 1800s, when many modern Western museums were being established, whales were a massive (pardon the pun) drawcard for these institutions.

‘We can’t see them up close except for the very rare encounter when a whale comes in close to a boat or close to shore,’ Kate says.

‘But you can get that sense of scale by visiting a museum.’

And this is perhaps what has captured the imaginations of museum designers across the world.

Whales take pride of place at many of the biggest museums around the world, but two of the most famous whales reside in the natural history museums in London and New York.

The London Natural History Museum’s ‘Hope’ whale skeleton was called a ‘sea monster’ by the villagers who saw it washed up on the shores of Wexford, Ireland in 1891.

The 25-metre-long skeleton is now suspended from the ceiling of the main hall.

The American Museum of Natural History, meanwhile, has taken a different approach to most by displaying a giant 28.6-metre-long model of a Blue Whale.

Its model has taken different incarnations since it first went on display in 1907 (the current version was crafted in 1968 and updated in 2003) and was based on photographs of a female that washed ashore in South America.

It wasn’t until 1970 that the first underwater photos of whales were taken, so models like this one have had to be updated and replaced to make them more anatomically correct.

Evolution in action

‘Whales are poster-children of evolution,’ says Erich.

‘Their skeletons in a museum setting are compelling evidence of evolution by natural selection and how major evolutionary transformations have occurred.

‘Melbourne Museum displays not only the blue whale, but a sequence of fossil whales vividly showcasing the physical evidence for how whales evolved from a seemingly unlikely land mammal ancestor.’

The value of collecting whale specimens is that it allows scientists to glean information about whale populations, their nutrition, size, and identification of different species.

‘Much of what we know about the biology of many species of whales—crucial to their conservation and management—is derived from their skeletons preserved and studied in museum collections.

‘The museum’s whale specimens are most often used in comparisons with fossil whale skeletons, to help uncover the evolutionary relationships of living and extinct whales, and to understand the anatomy and function of whales’ adaptations to life in the water,’ says Erich, referring to work he and his team are actively investigating.

Almost driven to extinction in the 1800s due to overhunting for their oil for lamps and soap and bones for corsetry, many whale populations rebounded thanks to the 1986 moratorium on whaling.

However, thanks to climate change, pollution and ocean traffic, whales are in danger once again.

‘Whales are the sentinel, or the canary in the coal mine if you like,’ explains Kate.

‘They tell us about the big processes that are happening now and have the potential to radically alter and disrupt our diverse marine ecosystems.’

Close to home

The Melbourne Museum’s Pygmy Blue Whale became stranded in Cathedral Rock, near Lorne, in 1992.

Whales become beached for all kinds of reasons, however research undertaken on this specimen indicates that it wasn’t feeding well at the time.

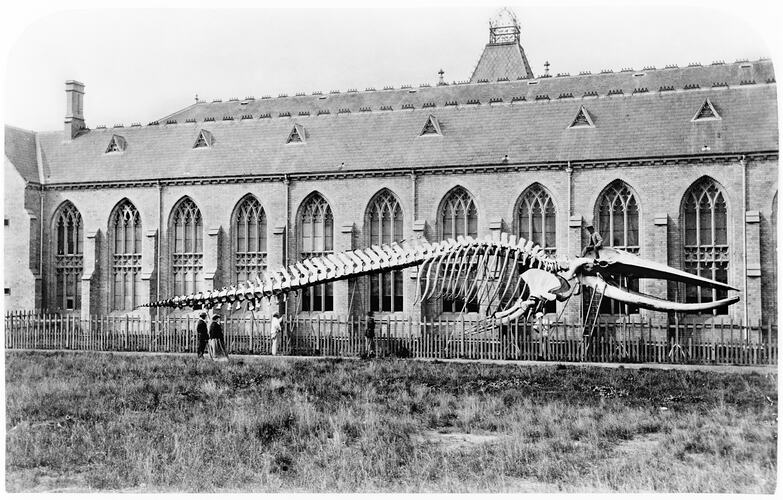

The display of a whale skeleton at Melbourne’s natural history museum also goes right back to its beginnings, decades before London or New York.

The largest articulated whale skeleton in the Southern Hemisphere was collected from Jan Juc, south west of Melbourne, and displayed outside—literally—Museums Victoria’s previous home at the University of Melbourne in 1867.

Given its exposure to the elements, the specimen quickly deteriorated.

All that remains of the skeleton today is some baleen (hair-like plates whales use to filter their food from water), but even these small remnants are still being studied more than 150 years later.

Needless to say, we are much more cautious about displaying, preserving and researching whale skeletons now.

Reflections

Whales are a lot like us, even though it might not be immediately apparent.

They are mammals, sharing traits like hair, bones, and genes.

Some species possess spindle neurons—previously only thought to be possessed by humans and great apes—which allow them to express empathy and form speech.

Add to that their matriarchal social groups and the fact that the mothers suckle their young, many of whom stay close by after maturity, and it’s no surprise that we have such an affinity with whales.

‘In all the four billion years of life on Earth, our species just so happens to co-exist, in this geologic blink-of-an-eye, with the Blue Whale—the largest animal ever to have lived,’ says Erich.

‘Consider how extraordinarily unlikely this coincidence is; how lucky we are to share our blue marble with this animal; and the responsibility we all share to ensure that it and its habitat survives.’

Something to ponder the next time you see one in the wild or, more likely, in a museum.