What can I find on the beach?

Victoria’s beaches are wondrous environments. Get to know the biodiversity of your local coast and see if you can find these 10 things on the beach.

Remember—admire and take photos of the amazing things you find on the shore. But once you’re done, leave them where you found them so that they can remain part of this incredible ecosystem.

1. Moon Snail egg mass

This tube of jelly was made by a snail!

While it looks like a jellyfish, this is the egg mass of a Moon Snail. The snail lays tiny eggs in the stiff jelly, which absorbs water and swells into a distinct, curved sausage shape. The egg mass can be up to 25 cm long—three to five times bigger than the snail that laid it!

After a few days, the egg mass will break apart in the water. The tiny snail larvae can then drift into the open water to feed and grow.

2. Port Jackson Shark egg

This brown, leathery corkscrew is an egg from a Port Jackson Shark.

The Port Jackson Shark’s egg is about the size of a human adult’s palm, and the corkscrew shape has an interesting purpose. After laying, the mother shark picks up the egg and forces it into a rocky crevice, its clever corkscrew shape helping it wedge in position at it hardens.

A Port Jackson Shark lays up to 16 eggs. The baby sharks grow inside the eggs for about a year, and most shark eggs that wash up on the beach are already empty.

Shark eggs are sometimes called mermaid purses—can you imagine why?

3. Cuttlefish bone

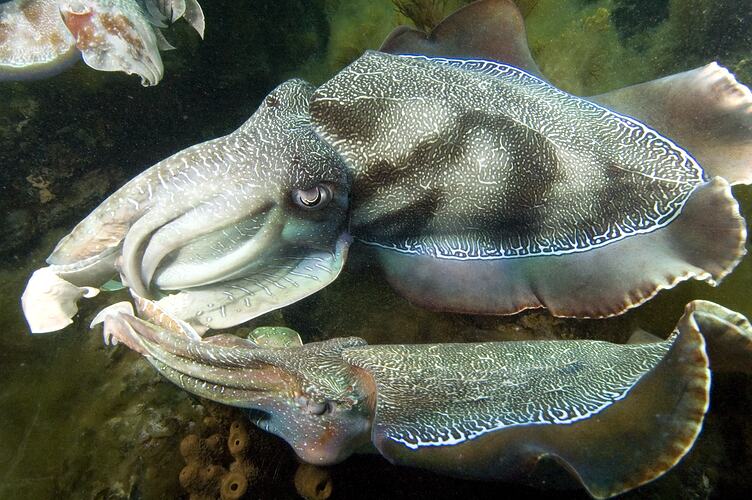

The cuttlefish bone (or cuttlebone) is a shell.

Cuttlefish belong to a group of animals called molluscs, which include creatures like snails and clams. Molluscs usually have squishy bodies with a hard, protective shell.

So where is the cuttlefish’s shell? The shell is inside the body, supporting the animal just like a bone. When the animal dies, this hard shell can wash up on the beach. The shell is what we called the ‘cuttlefish bone.’

The cuttlefish bone pictured above is from a Giant Australian Cuttlefish—the largest cuttlefish in the world!

4. Chitons

This little armoured mollusc is a chiton.

Chitons can be found on rocks and in crevices along the shore. They’re well-camouflaged, but can be spotted if you have a keen eye.

If you find a chiton, notice the eight shell plates on its back, surrounded by a fleshy skirt called a ‘girdle.’ The shell protects the chiton from predators and waves.

A chiton has a rough, rasping tongue called a radula. As it moves using its muscular foot, the chiton uses its radula to scrape delicious algae off the rocks.

5. Cone Shells

Do not pick up this shell.

This is a Cone Shell, and it’s a type of sea snail. These snails are amazing predators that use in-built harpoons to inject toxins into their prey.

Each species has its own toxin, adapted to take down its favourite food, such as fish or other snails. This one, the Anemone Cone, eats worms. It’s one of the few cone shell species in southern Australian waters.

The toxins of a Cone Shell can be very dangerous to humans, causing painful wounds, fainting and semi-paralysis. The venom from some tropical species can be fatal.

However, the snail’s venom may also hold the key to medical breakthroughs.

6. Barnacles

Have you ever looked closely at a barnacle?

Clustered on the rocks, each barnacle is an individual animal. Barnacles are a type of crustacean, just like crabs and shrimp.

As larvae, barnacles drift in the currents until they find a spot to attach, then stay put for the rest of their lives.

Can you see the plates which act as ‘doors’ to close the top of the barnacle? There are actually four plates, but one pair are much larger and easier to see. The second pair of plates is often hidden.

These plates open when the tide submerges the animal. The barnacle then extends its feathery limbs, called cirri, and waves them around in the current to catch tiny pieces of food.

7. Limpets

Limpets look a bit like barnacles, but they are completely different animals.

Limpets are snails! Instead of a spiral shell, they have a tent-like shell that protects them from hungry predators like crabs and birds, and from waves. The thick shell is difficult to grasp and hard to break.

Limpets move around the rocks, scraping off algae. They always return to the same spot on the rock to rest—their ‘home scar’. The limpet’s shell wears down an indentation on the rock where it can nestle in comfortably, trapping a bubble of water beneath its shell so it doesn’t dry out.

The grazing of limpets creates some bare patches and helps to maintain an overall balance in the number of algae growing on the rocks. These bare spaces are important habitat for animals like barnacles.

8. Sea urchin

This is the test of a sea urchin. The test is the hard outer shell that protects the soft insides and creates structure.

When alive, sea urchins are covered in spines. Look at the raised bumps on an urchin test—that’s where the spines have fallen off.

Urchins move around the rocks using sticky, tentacle-like tube feet that extend through tiny holes in the test.

Did you know that sea urchins are related to sea stars? They’re both types of animals called echinoderms, a group which also include brittle stars, feather stars and sea cucumbers.

9. Pheasant Shells

This lovely big shell is from a sea snail called the Pheasant Shell.

Pheasant Shells are smooth and shiny, with a long, pointed spiral. Like many other molluscs, these snails graze on seaweeds and seagrasses.

Habitats like seagrass are incredibly important for animals like the Pheasant Snail.

10. Sand!

Have you ever wondered about the sand between your toes?

The grains of sand come from all sorts of places, and can be different at every beach. Water breaks down rocks far away from the beach, carrying the tiny particles down rivers and into the ocean. Most sand is made from these tiny pieces of rock.

But sand also comes from living things. When you see a shell, whether it be from a snail, a barnacle or an urchin, imagine what might happen as that shell breaks down in the waves. Those tiny pieces of shell become part of the sand.

In tropical areas, sand can also be poop! Parrotfish munch and grind up the hard skeletons of coral. When the parrotfish poops, these ground out pieces of coral skeleton become white sand.

Got a question about something you found on the beach? Ask Us!

Our beaches are one of our planet’s thriving living systems. Experience other incredible connections that unite all life on Earth and visit the Our Wondrous Planet exhibition at Melbourne Museum.