The mighty Muirfield Seamount

By Dr Tim O'Hara

From ship slayer to protected wonderland, the Muirfield Seamount has a long history of surprising seafarers, including scientists aboard the latest voyage by Museums Victoria Research Institute.

The deep sea is still largely unexplored and unmapped.

Why? Because it is huge.

Approximately 50 per cent of our planet is covered in deep oceans, greater than four kilometres deep.

To address this gap, Museums Victoria has led a team of marine biologists from institutions around Australia on a 35 day, 11,000 km, voyage of discovery to Australia’s Indian Ocean Territories on CSIRO national research vessel (RV) Investigator.

We have been mapping sea-mountains and surveying the seafloor animals of these remote places.

The most impressive of all the seamounts is Muirfield.

In fact, it is one of Australia’s greatest mountains but you are unlikely to have heard about it.

It lies totally under the sea, 130 kilometres south-west of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, almost halfway between the Australian mainland and Sri Lanka.

It is a mighty sea-mountain, over 65 km across at its base—rising from a 4000 m deep seafloor to just 16 m below sea-level (by contrast Australia’s tallest on land, Mount Kosciusko, is just 2,228m).

That 16 m of depth is all important, because the summit is just deep enough to be invisible to passing ships.

This sea-mountain lurked undetected until 1973 when a large British cargo ship, the MV Muirfield of the Denholm Line, rammed the summit with its keel.

Nautical charts of the time indicated the ship was safely in 5000 m of water, but the MV Muirfield sustained enough damage to divert it to a dry dock in Singapore for repairs.

In 1987, the seamount was officially named after ship.

This incident has been used in the Mariner’s Handbook to illustrate the perils of relying too heavily on inexact maps.

That issue was addressed in 1983 by an Australian Naval Survey Ship, the HMAS Morseby, which located the seamount’s position for future nautical maps.

The Morseby was fresh from a mission to observe the Soviet recovery operation of an unmanned space shuttle prototype, 300 km south of Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

The Morseby used its small Bell helicopter to fly over obstructive soviet warships, dodging flares, to photograph the spacecraft being pulled from the water.

Finding Muirfield Seamount wasn’t quite as eventful, but at least ships could be sure of where it lay below.

Today, we have global maps of ocean depths from satellite measurements (that you can see if you use the satellite layer on smartphone map apps).

But this satellite data is far from perfect.

It lacks detail and its accuracy can vary with the density of rock, or nature of sand and mud on the seafloor.

For Muirfield Seamount, this satellite data ‘muddied the water’ as it didn’t show the summit in its correct position.

The summit was finally located with precision by an Australian Navy Laser Airborne Depth Sounder operation in 2012.

And so here we are, almost 50 years after MV Muirfield’s collision, mapping and surveying this seamount in all its glory.

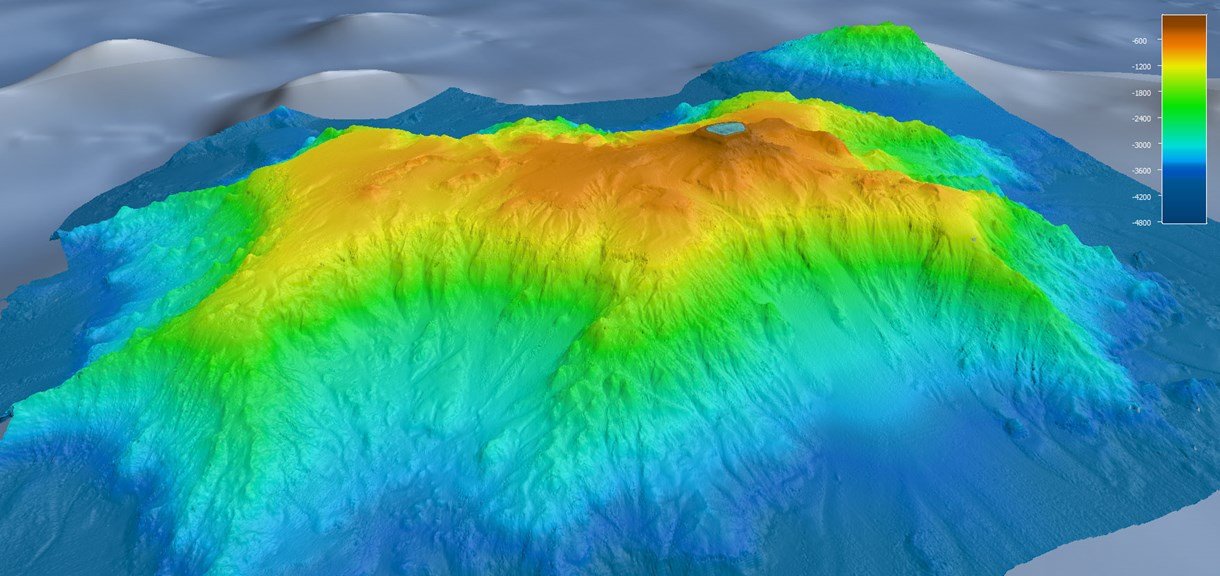

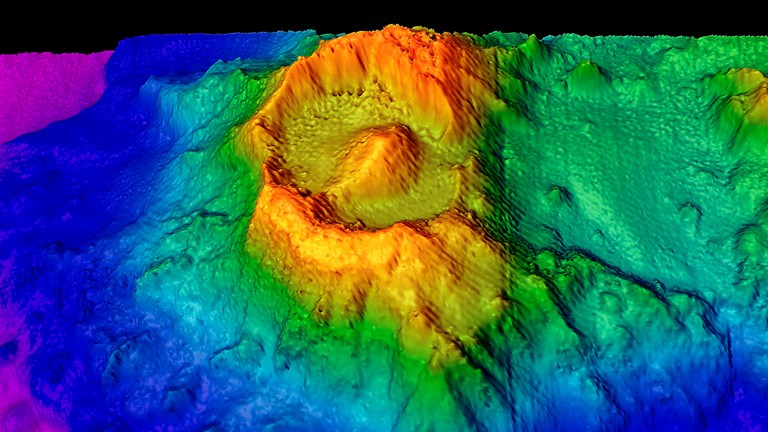

We can now reveal it in stunning detail from RV Investigator’s multibeam sonar, revealing a harsh landscape of ancient underwater lava flows, intersected with canyons, ridges and sand plains.

Many of the canyons have been created by great avalanches of sand and debris (possibly from earthquakes) that lie in piles at the seamount base.

The rim around the summit is covered in a coral reef, and fossilised coral rock is plentiful on the surrounding seafloor.

It appears that the top of Muirfield Seamount is a drowned atoll, where the corals could not grow at a fast enough rate to keep pace with the rise in sea-levels that have occurred since the last ice-age.

Biologists on the only previous scientific expedition to the Muirfield Seamount rather depressingly described it as ‘depauperate’ (scientific jargon for life having limited variety).

This is not our experience.

RV Investigator’s echo-sounders lit up from detecting schools of fish swimming around the seamount’s upper flanks.

Our deep-towed video showed gorgonian fans, colourful reef fish, crabs, seastars, and many other marine invertebrates.

Sharks patrolled the seafloor.

Further down we collected the oddly-shaped (but superbly adapted) deep-sea fish fauna, including the long-tailed snipe eel, fanged lizard fish, hatchet-fish with rows of bioluminescent lights along their bellies, and tripod fish that await prey by ‘sitting’ on three needle-shaped fins.

What amazes me, considering its remote location, is the diversity of life that actually lives here.

Every species has had to ‘accidentally’ arrive as larvae or adults, drifting or swimming from distant lands such as Indonesia, before settling and thriving here.

And marine species are highly adapted to distinct depth ranges—species that live at 500 m deep in Indonesia also now live at 500 m on Muirfield Seamount.

Imagine a series of horizontal highways of life extending through the oceans, connecting isolated specks of land.

Now Muirfield Seamount is entering a new phase in its history, as one of the standout features of one of Australia’s most recent protected area, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Marine Park.

This, and the Christmas Island Marine Park, co-designed with locals from both islands, were proclaimed in March 2022.

Together they cover almost as much area as the state of New South Wales, a vast new addition to Australia’s protected ecosystems.

Our maps and data will assist Parks Australia to manage the marine park into the future.

This research was supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.