The hidden history of Aboriginal stockwoman

As told by a Koa stockwoman, mother and doctor of philosophy.

Tauri Simone was 30-something and hitching her way back home from Darwin when she stopped in at pub in a dusty little town in western Queensland in the land of her ancestors, the Koa people.

She didn’t know it at the time, but that pit stop was the start of a journey which would see her become a stockwoman, mother and doctor of philosophy.

‘It kind of just happened,’ she says, 15-years later.

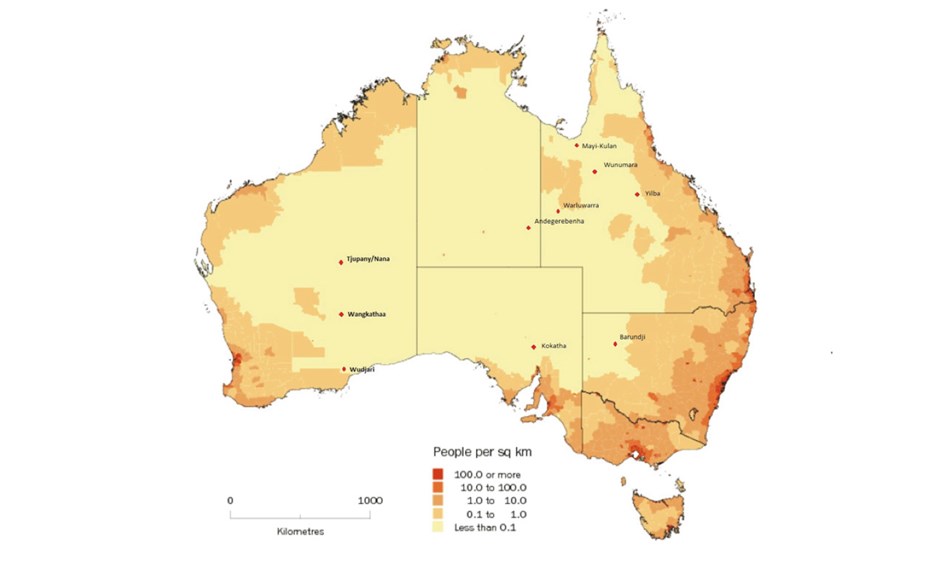

Over the next decade-and-a-half, she would work at 10 different cattle stations from Western Australia through South Australia and the Northern Territory to Queensland and NSW.

She’d take a boat through floodwaters to attend university and she’d raise a daughter.

But, through her research and first-hand experiences, Tauri would learn that her story was far from unique.

Tauri, or Dr Simone as she is today, would uncover a rich vein of stories. Stories that had been forgotten and suppressed.

She would learn that, as an Indigenous stockwoman, she was continuing a history that stretched back to around the 1860s.

Uncover the stories of women who overcame gender barriers by binding their chests and cutting their hair short to pass as men.

Women who kept isolated stations fed and watered with their knowledge of bushtucker and gnamma holes.

Women who mustered, rode boundaries and kept frontiersmen safe in their pioneering journeys.

‘The men couldn’t have done it without Aboriginal women,’ Dr Simone says.

Here are their stories, as told by Dr Tauri Simone.

My name is Tauri Simone and my connections to Country come from Winton, so all my family is from the Winton Channel Country, which is Lai Lai Dreaming, which connects us all to Kati Thanda, Lake Eyre. But I grew up around North Brisbane, the Glasshouse Mountains, Bribie Island.

Basically anywhere on that whole coastline was my backyard, because it was easy to just drive down to the Gold Coast or the Hinterland, or up the coast somewhere for a few hours. The outdoors were just a big playground really, and we did a lot of camping and playing in the bush.

My journey into becoming a stockwoman wasn’t something I planned. I had participated in some horse riding and competitions with Droving Australia as a teenager, but it wasn’t until my early 30’s that I found myself getting involved in the pastoral industry. It kind of just happened. I was travelling in a truck on the way back from Darwin one day and stopped at a little pub called the Blue Heeler Hotel in a little town in Queensland.

I ended up getting a job there, and chatting to all the stationers and workers from surrounding stations who travelled hundreds of kilometres to their local watering hole. I was fascinated by their stories. So a few months later I went out to a station myself, just north of Julia Creek, and started cooking for a couple of workers there. And that was the start of the journey that has now seen me on 10 different stations and 14 moves over the last 15 years! Working and living on stations just became my life.

As someone who grew up on the coast and lived at the beach, cattle station life was far removed from my familiar comforts. However, I know that my ease of adjustment to the industry comes from my spiritual connection to Country and the Ancestors in being able to navigate my way on the frontier. It is the spiritual connection that aids me in being able to work within the industry, and I believe it is important for Aboriginal people to have that connection to Country, as it can help heal trauma from the past and present. Connection to Country is everything to me. I think that is why the industry has been an important part in helping me to find myself. If you look after Country it will look after you.

My first real role as a stockwoman was on a station 100 kilometres into the Territory from Queensland. This station was the closest one I had experienced in using cattle strategies that were used by early pastoralists, due to the lack of modern conveniences. Fresh food was a luxury and tin food and salted meat were the main food source. There was only generator power which ran for three hours in the morning and three hours at night from 6pm to 9pm, however, there was solar electricity which was used for keeping the cool room running during the day.

Accommodation was a donga and not of great standard, but at the end of the day all you want is a bed to lie in. The days were long, hot, humid, and dusty and there was the constant pestering of flies, which one soon became accustomed to. Some days it would be well after dark before I would return to the head station. Trips to town which were approximately a six hour drive down a dirt road to Alice Springs would be done roughly once a month. I would normally spend about three to five days in town before returning to the station.

I feel people think that when you live on a cattle station that you are working with cattle constantly, which is far from the truth. There are so many more jobs that need to be done from yard building and maintenance to fixing, cleaning and building new water systems. Mending fences is a constant battle, and then there is road maintenance too. On some stations I’ve worked on a constant job at certain times was the eradication of weeds. Obviously, a major part for a stockwoman is working with cattle and this can be anything from mustering, trapping, processing of cattle to working with weaners to educate them.

I started going to University around the same time I started working on stations. When I went to Uni people would be amazed that I lived on a cattle station, but I mean hundreds of people live on cattle stations. It can be a tough industry though, and you have to love it to stick with it. I’ve been stuck in three floods, I’ve caught a boat to University, I’ve caught a helicopter, I’ve caught a bus! And I had a daughter in that time too, so balancing the whole three – work, Uni, motherhood.

I’d been working as a stockwoman for four years when I decided to start my Honours degree. By this stage I’d been on stations connecting to Country and talking with family and community a lot, especially the older generations who would tell me all kinds of stories about their experiences. That’s what you’ve got to keep in mind – there is probably not an Indigenous family in Australia that has not been either directly or indirectly impacted by the cattle industry in some way or another. So there’s a lot of stories to be told.

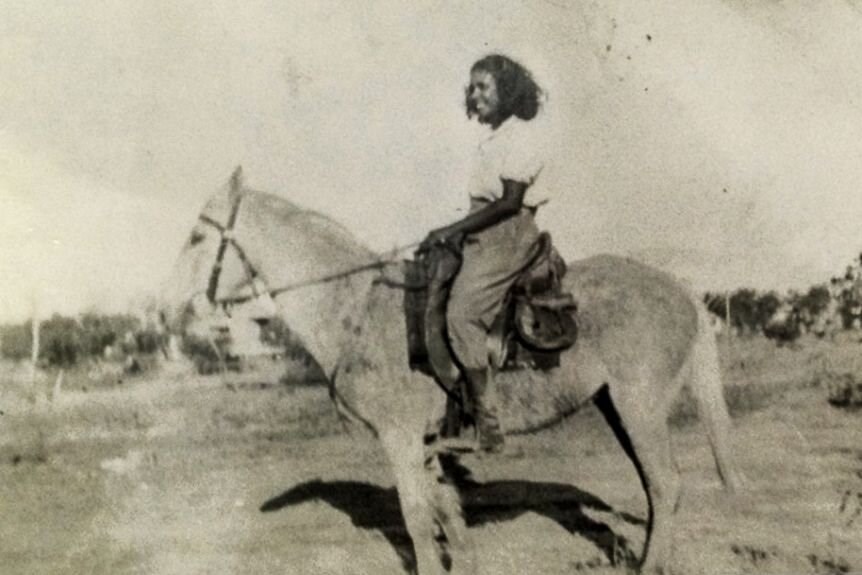

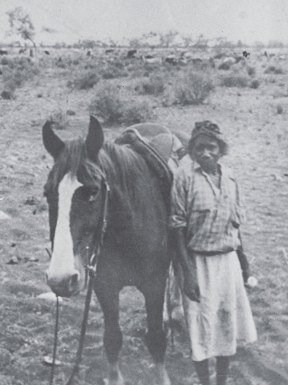

When I started my honours research I came across multiple sources of information about Aboriginal men who had participated and had played significant roles within the pastoral industry, but only negative research on Aboriginal women and their role. This inspired me to research and discover, although difficult and traumatic at times, the significant role that Aboriginal women played in the industry as stockwomen. I discovered some Aboriginal women from around the 1860s who had worked as stockwomen, and my interest just sort of grew from there.

I ended up writing a PhD, which was titled, “Aboriginal Stockwomen: Their Legacy in the Australian Pastoral Industry”. This research investigated the role that Aboriginal women played in the establishment and continuation of the Australian pastoral industry, and how Intellectual Cultural Knowledge was able to be continued. The research challenged existing beliefs and accounts that Aboriginal women were merely servants or sexualised objects, highlighting their importance in the industry through their lived experiences.

Aboriginal women completed a wide range of jobs in the establishment and continuation of the pastoral industry, such as yard building, fence building and or repairs, road building and homestead building. Once built, there was continual maintenance, tending of gardens, the care and welfare of animals such as goats, chickens or pigs, the killing of goats or on some occasions cattle for food and the tanning of the skins. Aboriginal women would participate in all aspects of station life. They would even be left to care for non-Aboriginal children. This was just the general station work.

Aboriginal women also made a significant contribution as stockwomen, from mustering, to yard work from drafting to the processing of cattle, boundary riders, becoming drovers and accompanying frontiersmen across the country, and in some instances ensuring their safety. A major find for myself was uncovering historical sources of women from the late 1880’s who had become Head Stockwomen, a position of high regard. These women’s knowledge of the environment, the seasons, the food sources available at various times of the year, how to find water or water sources and further to this, their understanding of animal behaviour. The men couldn’t have done it without Aboriginal women.

Thinking back to the late 1800s and 1900s across remote outback stations, can you imagine the difficulties accessing food when the nearest shop was 500km away by horseback? It could have been months before they accessed flour or tea or basic necessities. So Aboriginal women were supplementing station’s food sources with bush tucker, and knowing at different times where to find water, knowing about gnamma holes and trees that you could find water in. This all would have aided the pastoral industry greatly.

In early days Aboriginal women would have their babies and hop right back up on a horse and continue to work. The children would learn Intellectual Cultural knowledge but also all aspects of life on a cattle station. This knowledge was passed through generations. For myself and my daughter it has been a great journey of not only learning how to live on Country, but the cultural aspects of having connection to Country. If I was out mustering or in the yards, my daughter was always right there with me. It was more a matter of fitting her education requirements into the life, which with the help of School of the Air, was made possible. Formal education was not something women of the past had to contend with.

Overall I feel the most significant aspect of my research was to be able to give a voice to the women who were not given a voice, and who have been under-recognised, and under-acknowledged in regards to the significant role they have played. All of the women I’ve come across in my research were strong, resilient women at a time of adversity, tyranny and overwhelming racism and oppression. It’s important to remember the context – that a lot of Aboriginal women back in the 1800s and right up to the 1970s were forced into the industry and didn’t have a choice to enter it like I did. Missions came and went. Ration stations. Native police. All that really sad and terrible stuff. The biggest barriers for women in the earlier years was the violence against them from frontiersmen and the native police. Political policies also played a major role in barriers for women, as women were not supposed to be employed as stock workers. However, they would bind their chests and cut their hair short so they would look like men. They also had to contend with the government taking their children as they were born from relationships with non-Indigenous men.

I think one of the significant barriers for women of the past – and the present – is the patriarchal dominance of the industry by men. In cases where Aboriginal women work within an Aboriginal-owned station the barriers are more based on cultural aspects of what women should and should not do. This patriarchal dominance has led to an invisibility of women’s work. I often ask people the question, “what do you envision when you think of a cattle station”, and there is definitely still that stereotype of the white bloke in an Akubra hat, jeans and belt. That stereotype is so far from the truth. There are so many women, non-Indigenous and Indigenous, who have significant roles within the industry, and are making real impacts on the industry.

The truth needs to be told, and stereotypes need to be broken. My research was about bringing back some balance to history. Because of a lot of Australian history is forgotten. It’s not written about. Or it’s not recorded in the first place. For example, because Aboriginal women weren’t officially allowed to be stockworkers in those days, they were often hidden in official documents as men. In my research I could have been reading old government documents about women, but they were called “men” in the document, so it’s very difficult to uncover the truth.

It is also difficult to uncover truth when history has been written from a colonial perspective, telling only one version of a story. It is only through the decolonisation of non-Indigenous research of Aboriginal historical perspectives that the battle with colonial ideologies can end in a victory for the Indigenous – if we first make the colonial framework visible, then set about dismantling it and reconstruct epistemology, methodology and knowledge in our own image and our own terms. My research confirms through recognising and acknowledging the various roles of Aboriginal women’s experiences within the industry that they were significant participants as stockwomen. I feel honoured to be able to be the instrument in transcribing the oral knowledge to the written word and giving a voice to those who have been silenced.

Sometimes in my research I cried and cried, and then I got angry. It was a really emotionally challenging thing to research. This is why I tried to keep my research positive-based. I know some of the women’s experiences of course weren’t always positive, but they survived, and they were strong. They were resilient. I think that empowers our young to see that positive side to the story. They might be able to say “oh my grandmother was a stockwoman and I’m so proud of her.” I wanted to let them know that they come from a long line of strong, powerful women. And I wanted to provide a positive knowledge base for the children of the future to feel proud about where they have come from, to give a sense of hope of what their Ancestors may and did endure, and know that in tough times, they too can prevail.

Want to know more?

This story is based on interviews with Dr Tauri Simone conducted by Museums Victoria curator Catherine Forge in May 2020 as part of the Invisible Farmer Project.

Read Dr Tauri Simone’s PhD thesis here: http://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30092519/simone-aboriginalstockwomen-2017A.pdf