The 700

Hour after hour and day after day, they sit or stand together and meticulously break up rocks.

What they are doing is carrying out the final step in the search for, and the collection of, the fossils of dinosaurs and the other animals that lived with them in polar south-eastern Australia during the Early Cretaceous, between 105 and 130 million years ago.

Who are these people? Exactly what are they doing? And what brings them to do it?

There are more than 700 individuals whose combined efforts, starting in 1984, have brought to light these fossils in what has been dubbed by one of them “The Dinosaur Dreaming Project”.

When a rock is broken in two, both freshly exposed surfaces are carefully examined for any trace of a fossil bone or tooth. Of necessity searched for in this way, bones are commonly split in two. In that case, the fossil is exposed on both sides and the two pieces must be kept together to reassemble it in its entirety. It is either removed from the surrounding rock or an image made of it when still embodied within the rock by employing various scanning techniques. No trace of a fossil being found in the initial split - by far the most common outcome - the process is repeated. This goes on until either a fossil is found or the many fragments of the original rock are reduced to the size of sugar cubes.

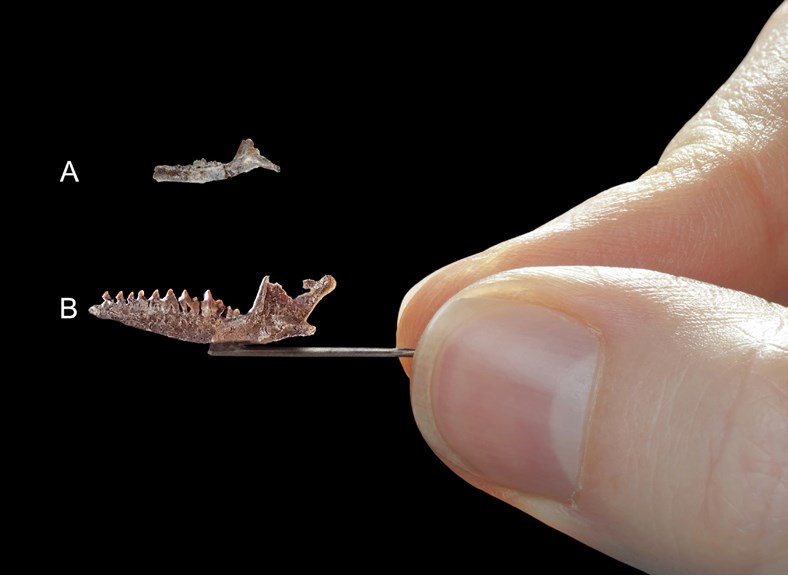

This size is the cut off because one of the most significant components of the fossil assemblages are the remains of tiny mammals that rival living shrews in size. In addition, many of the pieces of dinosaur bones that are found are only slightly larger than the mammals.

Beginning in 1978, fossil-bearing rock has been collected from the narrow shore platforms facing the Southern Ocean on the south coast of the State of Victoria. Three principal sites have been worked for more than a decade each. Extracting the hard, fossiliferous rock in the first place has been done by these same people in a variety of ways, depending on the circumstances of each site.

No doubt it was the word “dinosaur” that initially attracted the majority of The 700 to the project. Almost none had ever participated in a fossil dig of any kind in their previous lives, much less one focused on dinosaurs. To have the opportunity to do so was an alluring prospect.

Had there been a choice, where the initial dinosaur dig was carried out was the last place of the three locations, where major efforts have been made, that would have been chosen. Located in a small inlet from the Southern Ocean that was appropriately named Dinosaur Cove, the logistics of recovering fossils from there was so daunting that it was not the ideal place for only four experienced palaeontologists to train 68 volunteers, aged 7 to 77, in the rudiments of fossil collecting. But no other site of equal potential was known at that time. Although experienced myself, I had never been involved in cutting an underground adit in hard rock, or in anything else for that matter. Initially, except for a volunteer mine manager and his assistant, no one on the crew was experienced with the air powered jack hammers and drills provided by Atlas Copco.

But learn on the job we did. Working around the clock for most of the 16 maddest days of my life, an area about as large as two pay telephone booths was literally chipped out of the rock face. Night excavation ceased when a combination of high seas washing into the excavation site plus an electrical power failure forced the digging crew to climb out of Dinosaur Cove in darkness. That they did so when they did was fortunate because the next morning it was found that most of the tools had been washed toward the head of Dinosaur Cove by high waves. Others were lost at sea never to be seen again.

Out of that small area excavated came 85 fossil bones, of which a number were clearly those of dinosaurs. That experience demonstrated that dinosaurs could be found at Dinosaur Cove if an effort was made. Having at the time nowhere else to go in Victoria to collect polar dinosaurs and the other animals that had once lived with them, a full decade would follow with excavations at Dinosaur Cove every year but one.

Most of those who participated in the initial 1984 dig never returned. But out of that initial group, a few came back year after year. With their experience and devotion to the project, they formed the initial nucleus of a cadre of such people without whom the ‘Dinosaur Dreaming Project’, as it came to be known, could not have happened.

The cadre was never a formal group. In fact, the members of it would probably blush if ever referred to in that way. Rather, they were an informal family of people, who returned to successive digs year after year and became close friends. Those friendships, based on a common purpose that united them, were the glue which held them, and thus the project, together. For many, participation in a dig each year was something that they simply had to do. When a year came when a dig was not possible, many felt there was a hole in their annual calendar.

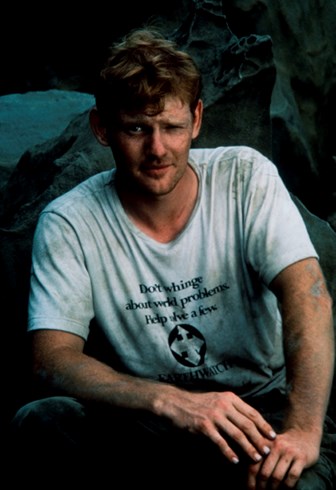

Fig. 5. (left) Lesley Kool. There at the beginning. Participation in the first dig at Dinosaur Cove whetted Lesley’s appetite so much that she volunteered to prepare the resulting fossils, that is, to extract them from the surrounding rock. Searching for new fossil sites with Mike Cleeland and others, she jointly found the second principal Victorian Cretaceous dinosaur locality, Flat Rocks, in 1991. Beginning in 1994, she supervised and organised excavations there for 21 field seasons. (Photograph by ©Peter Menzel/menzelphoto.com.)

Fig. 6. (middle) Mike Cleeland. Another “discovery” at Dinosaur Cove, Mike soon realised that his forte was not patiently excavating fossils at a known site. Rather it was searching for new ones. Persistence in this over more than a quarter of a century has led to the recognition of more than 30 sites along the Victorian coast, where many of the Cretaceous dinosaurs occur. Most significant of these was the third major Victorian locality, Eric the Red West, in addition to Flat Rocks, which he found with Lesley and others. An isolated find by Mike, which honours both Lesley and him, is a crocodilian-like amphibian, Koolasuchus cleelandi. (Photograph by Lesley Kool.)

Fig. 7. (right) Koolasuchus cleelandi. A restoration. This labyrinthodont amphibian is the last of its kind. When found, it was thought that the temnospondals, the amphibian group to which K. cleelandi belongs, had become extinct in the Early Jurassic. Extending the range into the late Early Cretaceous meant that Mike had increased the known duration of this group by 80 million years. (Art by Peter Trusler.)

For some, the commitment to the Dinosaur Dreaming Project was not only for the time when the dig was on. Rather, it became a year around commitment. The cadre was typified by people who saw a need and proceeded on their own initiative to fill it. Very rarely did I have to ask anyone to do something that needed to be done to make the project work. And even then, a casual suggestion of a need was enough to get one or more people to step forward and see that the need was filled.

When they needed something that extended beyond the time limits of an actual dig, there were those who took those tasks on as well. Sometimes, I was not even aware that a need had arisen and had been filled by one or more people.

Fig. 8.(left) John Wilson and Corrie Williams. Drillers! Here, these two long term volunteers are drilling a series of holes for explosives in a tunnel at Dinosaur Cove. Corrie’s job was to hold the drill steady when John began each hole so the tip remained in the same spot on the irregular rock face. Neither of them had done anything like this previously. One of the many examples of participants learning new skills on the job for the project to succeed. (Photograph by ©Peter Menzel/ menzelphoto.com.)

Fig. 9.(middle) Wendy White (left) and Mary Walters (right) sitting in depressions made by the feet of sauropod dinosaurs 95 million years ago near Winton, western Queensland.

Wendy is the year around organiser of the Dinosaur Dreaming project. Beginning with the initial dig at Dinosaur Cove in 1984, there has always been a summary report produced. This has evolved into the Dinosaur Dreaming Field Reports. Under Wendy’s guidance and editorship, it has become far more elaborate and informative. In addition to participating in each dig, she does much to keep all of the rest of us informed about what is going on relevant to the project as a whole.

Mary is an “almost ace fossil mammal finder”, as she has discovered four of the tiny Cretaceous mammals that are the central goal of the Dinosaur Dreaming Project (to me!), despite its name. She jointly discovered a fifth such mammal. This is why she considers that she has found four and a half of the sought-after mammals, not five, which would make her an ace. Having once proof read the entire Melbourne telephone directory (as a job), Mary lends a hand to Wendy while she is putting the finishing touches on the Dinosaur Dreaming Field Reports. (Photograph by Lisa Nink.)

Fig. 10.(right) The late David Pickering. Dave was, like Lesley, a master preparator of the tiny mammal jaws that were found from time to time. He also organised and ran all but

the most recent excavation at the Eric the Red West site, the final one of the three principal Victorian dinosaur sites to be found. (Photograph by Lisa Nink.)

Initially, I was involved directly with all aspects of the Dinosaur Dreaming Project. But the situation has evolved to the point where my role is to identify the objective, provide the logistical support necessary to carry out the objective, and finally to either carry out the resulting scientific analysis of the discovered fossils myself or organise for someone else to do it. The cadre now do all the intermediate steps, from systematically searching for and documenting potential fossil sites of interest, to preparing the fossils for study, to carrying out the fossil excavations with all the organising of people and equipment that it entails. Finally, an annual report is produced by the group intended both for the people who carry out the digs and the Friends of Dinosaur Dreaming, a support group for the project.

Fig. 11.(left) Nicola Sanderson nee Barton holding the walnut sized rock she had just found containing a fossil mammal jaw, which had been my goal for the 23 years since joining the staff of Museums Victoria. Besides being an important discovery to me, because of her discovery, Nicole returned to Australia from her home in the UK a number of additional times. In doing so, she met her future husband, Dale. (Photograph by Lesley Kool.)

Fig. 12.(right) Holotype of the fossil that Nicola found, Ausktribosphenos nyktos, after it had been removed from the walnut-sized rock.

If one person were to have put in all this volunteer effort that The 700 have done, it would have taken them at least 50 years of effort, seven days a week, all year round. So, what has made them do it? Yes, the word “dinosaur” got them started but surely it could not alone have kept them all going for all that time? To me, it seems that it was a combination of the associations and friendships with like-minded people, and the thrill of finding a significant fossil when you realise that, not only are you the first person to lay eyes on it, but that without your effort, it would be undiscovered.

Fig. 13. (left) Nicole Evered who rightfully takes great pride in having discovered the dinosaur Qantassaurus intrepidus. (Photograph by Wendy White.)

Fig. 14. (right) Restoration of the head of Nicole’s dinosaur. Qantassaurus intrepidus had an unusually short deep skull for an ornithopod dinosaur. It was the “bulldog” of the group. (Art by Peter Trusler.)

Had funds been available to hire all this human effort, it seems highly unlikely that all the enthusiasm, persistence and personal initiative, without which the project could not have succeeded, could have been purchased with mere money. Could a more meaningful honour be bestowed on anyone than to have others deeply desire to help them voluntarily in a myriad of ways to achieve their life’s most sought-after goal? The ultimate irony is that my primary goal was not to learn about polar dinosaurs, but rather the mammals that lived alongside them, the closest we can know about what our ancestors looked like all those millions of years ago. Despite having learned that this is actually the central objective, the cadre still continues to help achieve that goal.

Further reading

Rich, T.H. & Vickers-Rich, P. in press. Dinosaurs of Darkness. 2nd edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Vickers-Rich, P. & Rich, T.H. 2014. Dinosaurs of Polar Australia. Pp. 46-53 in Dinosaurs! Scientific American Books. New York.

About this article

This article was written by Dr Thomas H. Rich and first appeared in Deposits Magazine Issue 58 (2019).