Lunar New Year

This Lunar New Year, come for a tour of the Chinese Zodiac through the Museums Victoria collection.

Each of the 12 years of the Lunar Calendar is represented by an iconic animal.

According to the ancient legend, their order was determined by a race across a river to reach the Jade Emperor, who had invited animals from around the world to his palace.

In the Museums Victoria collection you’ll find a variety of these animals, each with their own story.

So, let’s take a tour through the Chinese Zodiac—with a twist.

Rat

As the tale goes, the rat is first in the zodiac because it won the race by riding on the back of an ox.

It’s a similar story for the first rats coming to Australia but, rather than relying on cattle, they rode on floating vegetation to make the crossing from Asia to Sulawesi, New Guinea, then Australia.

Just to be clear this does not include black or brown rats, which hitched a ride with Europeans; Australian native rats have been here for millions of years.

One of the most specialised, and largest, is the Common Water Rat, Rakali.

This species is well adapted to its semi-aquatic lifestyle—with partially webbed hind feet, and water-repelling fur.

A Rakali specimen in the museum’s collection was even used to sequence the species’ genome for the first time in 2017.

Not sure how to tell your native rats from introduced species? Here is a handy guide.

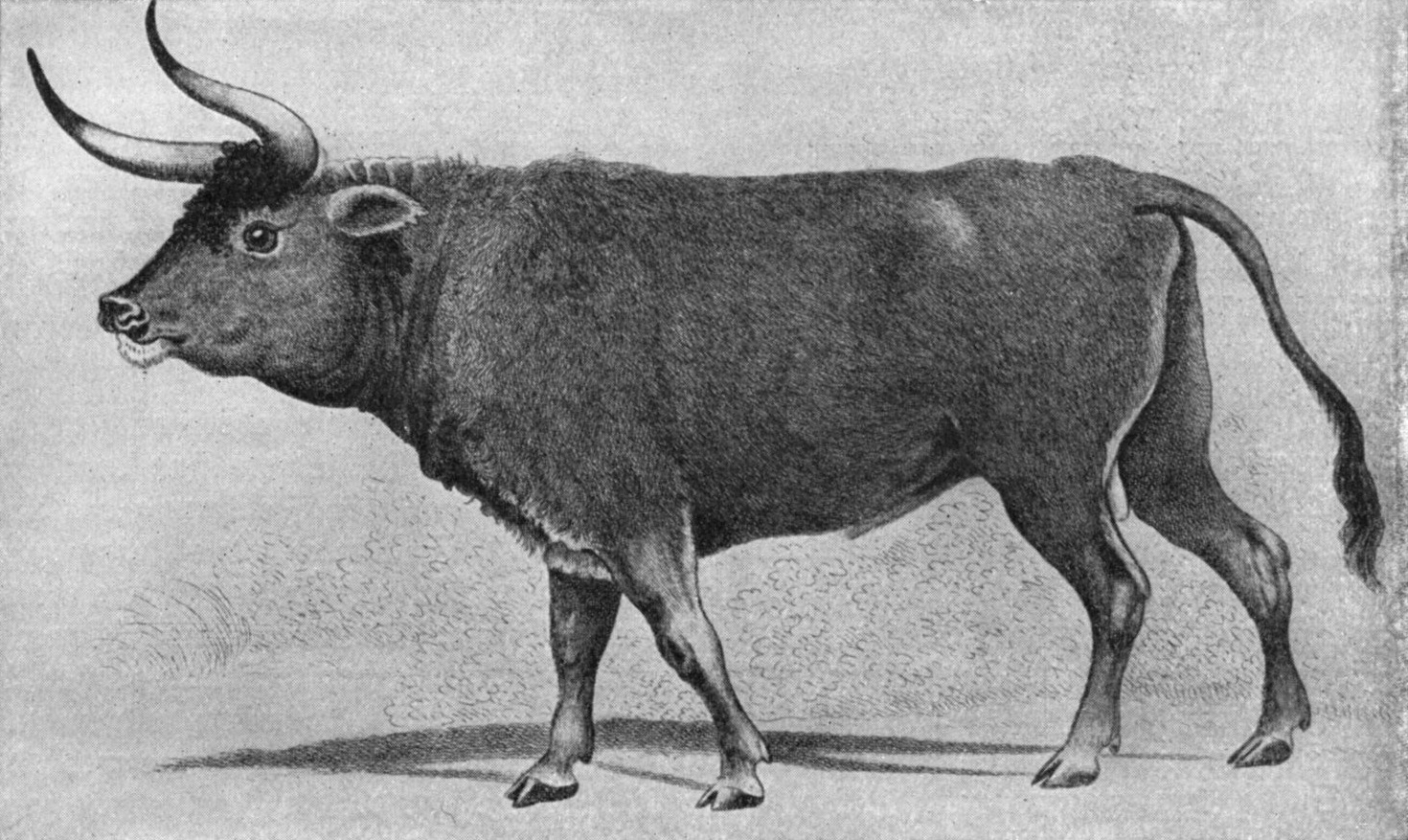

Ox

Australia is all too familiar with the ox—the name given to cattle that have been trained for work.

The ancestor of modern cattle though, the Aurochs, was so big that Roman emperor Julius Caesar called them ‘a little below the elephant in size’.

This bovine megafauna once roamed across the Asian, African, and European continents but the last of the species died in Poland in 1627.

Aurochs are well represented throughout human history—from cave paintings, to fossilised specimens in museum collections, like ours.

However, scientists in Europe are attempting to bring them back by selectively breeding domestic cattle that display the traits of their ancient ancestor.

Tiger

Australia has its own list of creatures that carry the tiger moniker, but in this instance we’ll stick with the Tasmanian Tiger.

While the museum has several specimens of this iconic, extinct species, there are a two notable examples.

One is a visitor favourite that has been in the museum’s collection since 1869.

In those more than 150 years, it has made an appearance at nearly every home of Melbourne’s natural history museum since.

Another notable Tasmanian Tiger in the collection is a quite rare—a pouch young, preserved in ethanol.

It is one of four young to be recovered from a female Tasmanian Tiger, that came to the museum in 1909.

This specimen has allowed scientists to learn much about Tasmanian tigers since their extinction, including sequencing the species’ genome.

Scientists are hoping to recreate the Tasmanian Tiger, using some of the knowledge gained from these specimens.

Rabbit

Unfortunately, the story of rabbits in Australia is not a happy one.

European rabbits have been introduced to Australia dozens of times, beginning with the First Fleet in 1788.

But it would take just one man and 24 rabbits to ensure their complete invasion of Australia.

In 1859 a wealthy settler named Thomas Austin imported the animals from England so he could hunt them for sport at his Barwon Park estate, near Geelong.

Austin was a member of the Victorian Acclimatisation Society—a group with the sole aim of introducing species to the Australian colony.

‘The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting,’ he wrote.

How wrong he was.

It took just 50 years for the rabbits to spread across the entire continent in the fastest invasion of its kind, anywhere in the world.

Despite many attempts to eradicate them, the descendants of Austin’s rabbits still plague the country to this day—a few examples of which you can find in the collection.

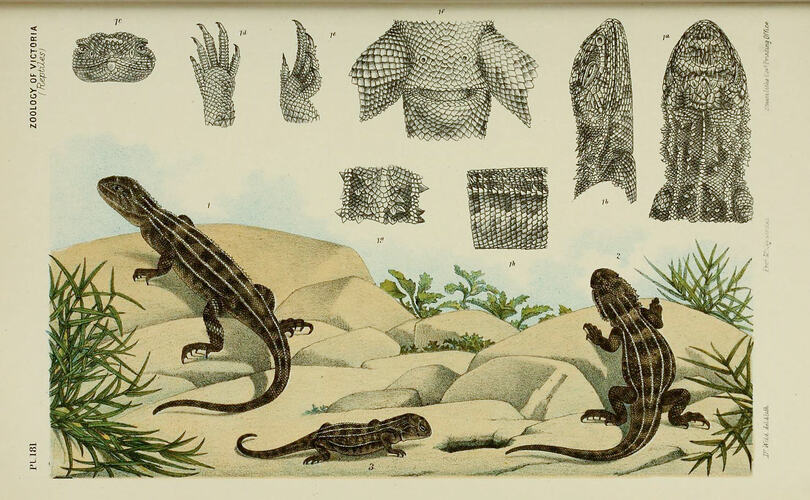

Dragon

Australia is home to many ‘dragon’ species, but perhaps the most elusive of these is the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon.

The most recent specimen was entered into the museum’s collection in 1967, but the last confirmed sighting of this species was just two years later, in Geelong.

Despite half a century’s absence, Museums Victoria Research Institute scientists are hopeful of finding the little dragon.

If not, this could be the Australian mainland’s first recorded extinction of a reptile.

Snake

Human relationships with snakes are complicated, and none more so than this Coastal Taipan from the collection.

It is the first taipan to be milked for venom, and the resulting antivenom subsequently saved many lives.

To the man who found it though, this snake brought tragedy.

In 1950 there was no antidote for the deadly venoms produced by the species, and scientists were intent on studying live taipans to produce it.

19-year-old herpetologist Kevin Budden found a large taipan in a Queensland garbage dump but as he was trying to transfer it to a bag, the snake bit him on his hand.

Kevin insisted the snake be kept safe and sent to Melbourne, before succumbing to his injury the following day.

Researchers in Melbourne milked the snake six times, after which it was preserved in the museum’s collection.

Commonwealth Serum Laboratories produced an antivenom by 1955, and it was first used to save the life of a 10-year-old boy later that year.

Horse

We couldn’t talk about horses without mentioning Phar Lap, whose name means ‘lightning’ in Zhuang and Thai languages.

Born in New Zealand in October 1926, Phar Lap was picked up at auction when he was 15 months old by Australian trainer Harry Telford.

Despite a slow start to his racing career, by 1930 Phar Lap was a household name in Australia—cemented by his victory in the Melbourne Cup that year.

Between September 1929 and March 1932, Phar Lap won 36 out of the 41 races he competed in.

But on 5 April 1932, having just beat the world’s best in North America’s Agua Caliente Handicap, it all came crashing down.

Phar Lap died of arsenic poisoning, and such was his fame that Australian institutions were intent on securing his remains.

After being prepared by the Jonas Brothers in New York, Phar Lap’s heart went to Canberra, his skeleton to New Zealand, and his mounted hide to Melbourne.

To this day Phar Lap remains one of the Melbourne Museum’s most popular exhibits.

Goat

Rather than focus on another introduced animal, let’s look at a native Australian that shares its name.

Goatfish are so-called for their distinctive chin barbels, which they use to probe the seafloor to smell or taste for food.

Individual fish are also able to rapidly change their colour patterns in response to threats.

Aside from in the museum’s collection, you’ll find the Bluestriped Goatfish along the southeastern coast of Australia.

There are also more than 25 other species of Goatfish elsewhere in Australian waters.

Monkey

Like rats, monkeys are thought to have crossed large bodies of water on floating vegetation to reach new continents.

Monkeys, however, never made it to Australia—the content had already drifted too far by the time primates evolved some 55 million years ago.

The Indonesian Island of Sulawesi was about as close as they got, which is where you’ll still find seven species of macaques.

The southernmost of these is the Moor Macaque, which is represented by this taxidermy mount in the museum's collection.

On the northernmost end of the island is the Celebes Crested Macaque, which famously took a ‘selfie’ on a wildlife photographer’s camera, triggering a copyright dispute in 2011.

Rooster

The chicken is the domesticated form of the Red Junglefowl, originating in mainland southeast Asia.

This specimen was collected in India by John Gould—the English ornithologist perhaps best known for his work on Australian bird life.

From the 1850s, the National Museum of Victoria’s first director, Sir Frederick McCoy, was keen to build up an extensive natural history collection.

Gould travelled the world collecting animal specimens and in 1857 McCoy wrote to him asking for, ‘as complete a set of good bird skins as can be obtained’.

Gould sent thousands of specimens to the museum over a decade, and this rooster is one of the early deliveries—registered in the collection in 1859.

As with many bird species, roosters, being the adult male, are significantly larger than females and display brightly coloured, decorative feathers.

Dog

Antarctic exploration wouldn’t have been nearly as successful without dogs like Ursa and Morrie.

Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink was the first to use dogs to haul loads in his voyages to the continent in the 1890s.

Huskies became the breed of choice after his compatriot Roald Amundsen used them to great effect in reaching the South Pole in 1911.

Australia brought a team of huskies to its first base at Mawson Station in 1954 and continued to breed them for use in Antarctica.

Ursa and Morrie were born in the same litter in 1985 and were inseparable—once the pair even escaped the station together and were seen jumping over snow drifts in unison.

They worked in Antarctica for six years until Australia signed the Madrid Protocol in 1991, that banned dogs to protect the environment.

Morrie was the last Australian husky to step off the continent when the final dogs left Antarctica in December 1993.

The pair came to Melbourne where they made public appearances to raise awareness of the role dogs played in Antarctica.

After they passed away, both dogs were brought into the museum’s collection in recognition of the role they played in Australia’s Antarctic history.

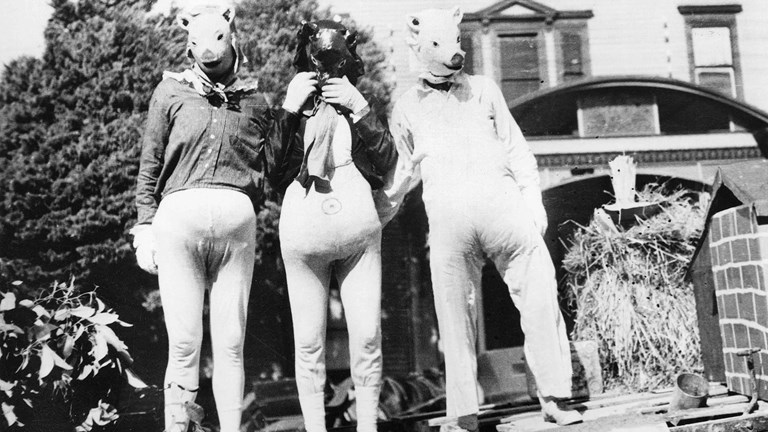

Pig

A pig in name only, this is evidence of another animal found in the museum’s collection that was here long before people.

It may just be a small portion of shell, but it belonged to a species of pig-nosed turtle that lived near Melbourne five million years ago.

At the time southern Australia had a warmer climate and was also home to animals like monk seals and tiger sharks.

But a rapid cooling and drying of the continent 3 million years ago changed all that.

Today, the only remaining species of pig-nosed turtle is found in more tropical regions in the Northern Territory and Papua New Guinea.

This fragment of the ancient pig-nosed turtle’s shell was collected at Beaumaris, a beach southeast of Melbourne, in the early 1900s.

It sat waiting in the museum’s collection until researchers realised what it was in 2021.

Happy Lunar New Year!