Know your bones: what is a ‘real’ fossil?

Fossils are the only means we have to study and display ancient animals, like dinosaurs and Australian megafauna, but why don't museums always display the originals?

Coming face-to-face with a dinosaur is an awe-inspiring experience and many of the Melbourne Museum’s visitors tell us they are blown away by the feeling of being dwarfed by giants like Triceratops and Mamenchisaurus.

So, it’s no surprise that one of the most common questions we get at the museum is, ‘Are the fossils real?’

This seemingly simple question can be quite difficult to answer—so, let's break it down.

What do we mean by ‘fossil’?

Before we can talk about the authenticity of fossils, we need to be clear about what fossils are and how they are formed.

Typically, when palaeontologists say ‘fossil’ they are talking about any evidence of a living thing that is more than 12,000 years old.

This might seem like an arbitrary cut-off date, but it refers to the beginning of the Holocene Epoch—the current geological period that we are living in.

Often the word fossil conjures up an image of towering skeletons left behind by dinosaurs but, in reality, they are a rare and hard-won part of the fossil record.

Dinosaurs are just one distinct group of reptiles and many of the fossilised bones that palaeontologists work with are from mammals, amphibians, and fish.

Additionally, most of the fossils in our collection come from animals that don’t have bones at all—organisms like hard-shelled sea creatures, plants, and even insects.

The majority of fossils we find have gone through a geological process that impregnates them with minerals.

For this to occur the organism has to be covered by sediment soon after death, usually by mud or silt.

Water carrying dissolved minerals seeps into tiny holes and gaps in the organic material.

Once inside, these minerals form crystals and begin to fill the empty space within—something that can take millions of years.

While these processes can vary, the most extreme example is known as replacement.

This is when all of the organic material in a specimen decays and disappears, leaving behind an empty cavity to be filled in by a perfect mineral-based copy—much like a mould.

Known as replacement fossils, these can even be formed by precious minerals.

One step down from this is a more common process known as permineralisation.

‘Permineralised fossils aren’t copies – they still contain part of the original animal,’ says Museums Victoria palaeontologist Tim Ziegler.

‘The process has added minerals from the environment into open space in the bone, and into the bone’s chemical structure.’

Sometimes we find unaltered fossils, or remains that are older than 12,000 years, that haven’t been through any geological changes.

These are typically remains that are preserved by being trapped in tar, frozen earth or, more commonly in Australia, dried out in a cave or a sand dune.

To make things even more complicated, some fossils aren’t even part of an animal but rather something that an animal left behind.

We call these trace fossils and they can include things like eggs, burrows, footprints, and even poo!

So where does this leave us?

The consistent traits that make a fossil ‘real’ are that it is old and the animal, either directly or indirectly, had some part in making it.

While near-complete specimens, like our Triceratops, are amazing spectacles it is not always possible or practical to use real fossils for a public display.

Piecing the past together

Sometimes in a museum setting, our only option is to use casts of fossils.

While replacement fossils are a geologically produced copy, casts are a human-made replica.

We have an entire team at Melbourne Museum who create these hyper-realistic replicas for us.

This team of talented people, known as preparators, also create models of some of our other museum objects and prepare new taxidermy specimens for display.

These replicas can be made of different materials, depending on what they’re being made for.

‘Polyurethane foam is our most common material as it tends to be much lighter, but we also use fibreglass for some smaller dinosaurs,’ says Steven Sparrey, Museums Victoria’s manager of preparation.

No matter the material, Museum Victoria’s preparators work hard to make sure that our fossil replicas look as close as possible to the original by using silicon moulds made from the original fossil.

This means that every crack, every indentation, every bump that’s present on the original fossil is also present on the replica and the two are visually indistinguishable.

So, why would museums use replicas over the original?

Preservation

Permineralised and replacement fossils can take millions and millions of years to form, which means they cannot be replaced if something unfortunate happens to them.

They can also be surprisingly fragile, and very sensitive to temperature and humidity changes.

Sometimes museums will make a copy of the fossil so that visitors can get up close, while keeping the original safe for palaeontologists to study.

This also allows us to take our replica fossils on the road as part of our Outreach Program and show them to people all around Victoria—like we do with our amazing Tarbosaurus.

Research

One fossil can only be studied by one person at a time but if we make 10 copies of the fossil, it can be studied by 10 different palaeontologists at once!

Similarly, it means that the same fossils can be displayed in different museums across the world and enjoyed by as many people as possible.

Many of the fossils found in Melbourne Museum’s Dinosaur Walk are replicas of fossils displayed in other countries, that were loaned to us as part of a touring exhibition in 1980.

‘It was the first time we had that many big dinosaurs of any kind travelling through Australia,’ explains Tim.

‘That exhibition made history in its day, and this is the payoff...we can continue to use them to create this display.’

Modern solutions to ancient problems

Sometimes fossils are so delicate and fragile that they can’t safely be removed from the rocks that they are found in.

In cases like this, palaeontologists sometimes use X-Rays to create a digital 3D model of the fossil.

Preparators can then use this digital model to create replicas of fossils that we’ve never even seen!

In recent years museums have even been able to 3D print fossil replicas, making them cheaper and easier than more traditional casting methods.

It also means that people at home can make their own replicas of fossils held by museums, like our Pleuroceras ammonite.

Practicality

Like a lot of things that we pull out of the ground, fossils are HEAVY—understandably so, given they are mostly made up of rock.

This means that sometimes, they are just too heavy or fragile to put on display while keeping visitors safe.

And it is here where lightweight casts are an advantage over the originals.

In these situations, museums might use a resin replica to hang from a ceiling, like our beautiful Anhanguera.

Flexibility

Like all good scientists, palaeontologists are regularly making new discoveries and updating their knowledge accordingly.

And sometimes these discoveries tell us new information about how dinosaurs probably behaved and moved.

If a museum is using replica fossils, this means they can easily modify the poses of dinosaurs to better match our knowledge about how they lived.

Our palaeontologists at Melbourne Museum recently learned that sauropod dinosaurs walked with their necks held forward at an incline, rather than vertical, and our preparators were able to adjust our Mamenchisaurus accordingly!

Incompleteness

Dinosaur fossils are really, really, hard to find.

Even when we do find one, we very rarely find the whole skeleton.

Some animals might be disturbed by predators before they fossilise, while others might be affected by geological mishaps during the multi-million-year process that is permineralisation.

This means that even when museums do want to display actual fossils, they often have to rely on replica parts, made by preparators, to fill in the gaps.

Even a specimen like the Melbourne Museum’s Triceratops is only 85 per cent there—and that is the most complete one ever found!

Steven says with something like that, his team has to get creative: ‘We actually had to create missing parts of the skeleton from photos of overseas exhibits or estimates from our palaeontologists’.

But as Tim points out the museum has made sure to keep those artificially modelled parts obvious, even to a casual observer.

‘Someone can look at it and think, “wow, that’s the only part that’s not original, that’s the only part that didn’t make it” and I think that’s really telling.’

Just answer the question!

So, what about our original question, are our fossils real?

In the case of casts, no.

These replicas are not part of the fossil record but they are reproduced with such accuracy that they are valuable both for scientific study and display, without risk to the irreplaceable originals.

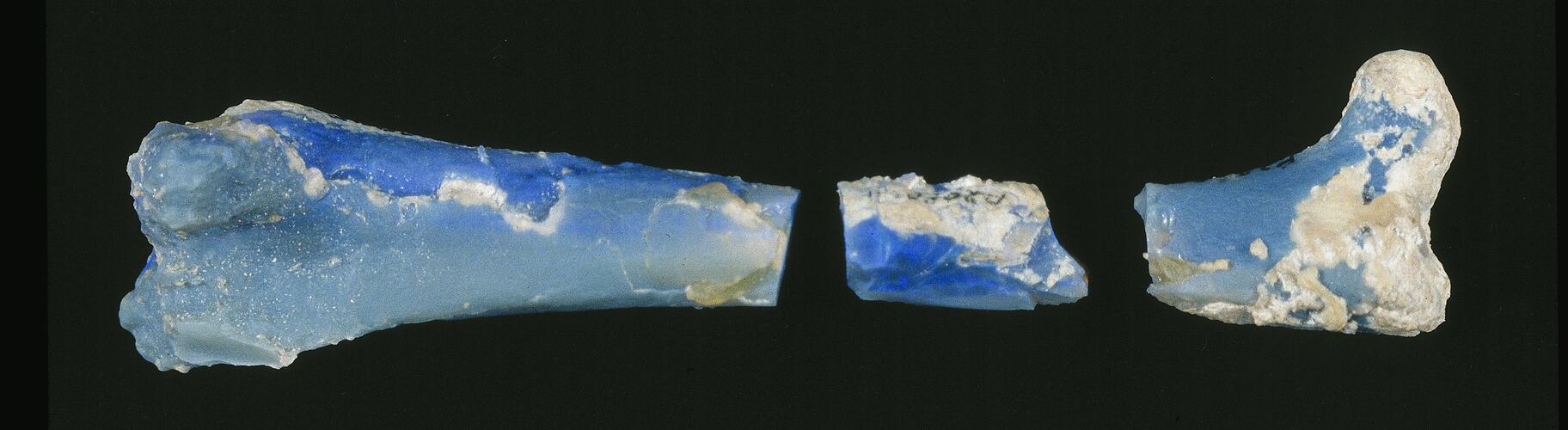

They are as real as a human-made replica can be, as you can see with the Mammalodon jaw above (the original is on top).

As for the authenticity of unaltered bones versus permineralised or replacement fossils—this is probably a better question for a philosopher, rather than a museum.

In fact, the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato even had a thought experiment that summed the question up nicely.

Plato told a story to his students about a ship captained by a very successful hero named Theseus, whose ship was never damaged or destroyed.

But, as it was made of wood the ship did decay—similar to our dinosaur bones.

Over time, each plank of the ship was replaced with new wood as older pieces rotted away and eventually, though the ship remained, not one piece of it was original—it had all been replaced.

As Plato asked his students: is Theseus’ ship the same one he started with, or is it just a copy?

And now we ask you—if some, or all, of the original material within a bone has been replaced with minerals, is it still ‘real’?

Like all good philosophical questions, that’s up to you to decide.