How do deep-sea creatures survive in the crushing dark?

Meet some of the weird and wonderful animals that have adapted to life in the deep sea.

The deep sea can seem like a strange place—often portrayed as a vast expanse of pitch-black ocean sparsely populated by alien creatures.

But thousands of metres below the ocean’s surface are thriving ecosystems.

Research expeditions provide a window into this world where massive underwater mountains harbour an incredible variety of marine life.

These deep-sea creatures may seem weird to us land-dwellers, but it is only because they have specifically adapted to these extreme environments that are so different from our own.

Let’s meet a few found aboard Australia’s marine research vessel, the RV Investigator.

The twilight zone: 200 to 1,000 metres below sea level

Most of the ocean’s life is found within 200 metres of the surface (known as the Epipelagic or sunlight zone) but beyond that most of the available light is gone, along with all the animals that rely on photosynthesis to survive.

It is for this reason that you find many creatures in the twilight (or Mesopelagic) zone that make their own light, using bioluminescence.

One such animal is the Cookiecutter Shark, so named for its habit of cutting small circular chunks out of much larger prey—including other sharks, whales, and even submarines (yes, really).

This small shark employs a tactic known as counterillumination—by using an array of light-emitting organs on its underbelly it can offset any light from above, effectively camouflaging it from predators.

Cookiecutter Sharks also take part in the greatest migration phenomenon on earth—diel, or daily vertical, migration—heading to the surface to feed at night but diving back down to the deep sea during the day.

A sound strategy for most creatures, unless there is something waiting for you.

Dragonfish hang in the water column, waiting for their vertically migrating prey to swim past.

Their own counterillumination ensures they won’t be seen until it is too late.

Another trick some dragonfish have up their sleeves is they can see, and emit, red light—a rarity in the deep.

Red light has the longest wavelength, so it’s the first to be filtered out by the water at about 100 metres below the surface.

Many deep-sea creatures are red for this reason as it makes them effectively invisible.

Except to dragonfish, which use bioluminescence to expose their prey.

Unfair, sure, but that’s life in the deep—you take whatever advantage you can get.

The midnight zone: 1,000 to 4,000 metres below sea level

Down here (also known as the Bathypelagic zone) there is no light from the surface, so any animals must be well adapted to life in the dark.

It’s cold too—about four degrees Celsius, or the same temperature as your fridge—and only gets colder the deeper you go.

Whales and some seals may occasionally venture this deep, but this isn’t exactly a friendly place for air-breathing mammals.

Most animals this far down are relatively small because food is scarce.

One of the biggest specimens found on a recent voyage near Christmas Island was a one-metre-long Brunswig’s Cusk that came up from about 1,500 metres.

Squat lobsters (also confusingly not a lobster; more related to a hermit crab), only grow to be a few centimetres but their claws can make up nearly half their total length.

They are found anywhere from thousands of metres below the surface to shallow tropical reefs.

In the midnight zone, it’s common to find them attached to bamboo coral.

From this position they can hang on with their legs, leaving their pincers free to grab any food that floats by.

The open ocean is a dangerous place unless you are at the top of the food chain.

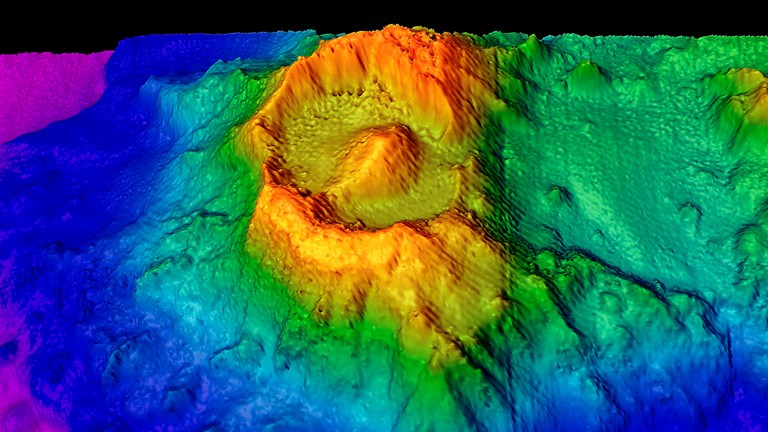

Seamounts provide shelter for many creatures and serve as focal points where currents swirl, bringing nutrients from above and below.

Like a whale carcass sinking to the sea floor, seamounts can be the foundations for entire ecosystems.

Barnacles, corals, glass sponges and urchins can be found clinging to the side of seamounts at this depth.

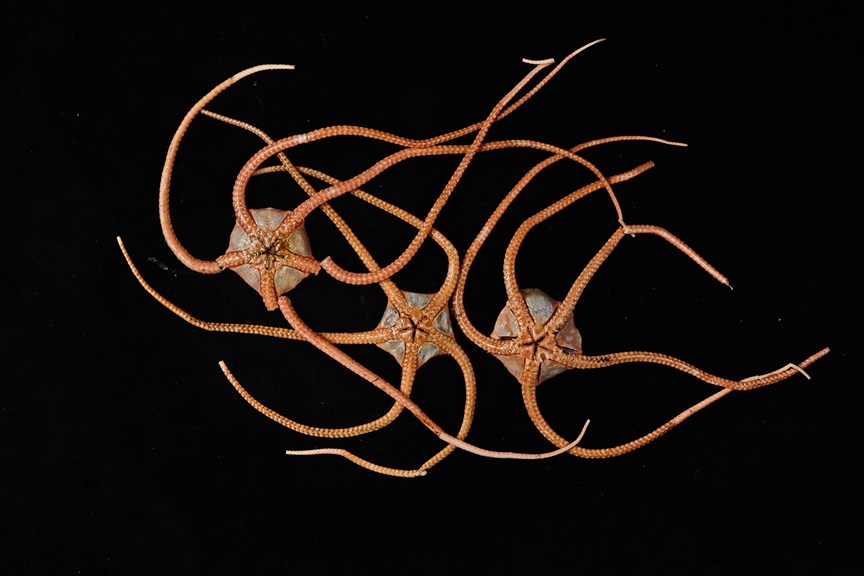

One of the most abundant creatures, though, are brittle stars—the crew of the Investigator found 46 species just around Christmas Island.

They can be found all around the world and at almost at any depth.

Brittle stars, or ophiuroids, come in all shapes and sizes but part of the reason for their success is they aren’t picky eaters.

They use their tube arms to grab floating organisms and organic matter and direct it to five jaws on the underside of their central body disk.

But what if you’re small and don’t have arms?

You need some serious teeth to make sure your food doesn’t get away.

Meet the fangtooth—an appropriately named fish that has massive fangs, relative to its body size.

It needs special sheaths in its upper jaw to make sure it doesn’t stab itself in the brain.

What if you’re still small but don’t have arms or big teeth?

Anglerfish are renowned for using bioluminescence to lure in prey, but not all of them are terrifying; some can be quite cute, like the boggle-eyed batfish (also known as the Lesser Handfish).

This batfish uses modified fins to ‘walk’ along the sea floor, using a lure near its mouth to attract food.

It is also covered in slender spines, giving it a velvety appearance.

The abyss: 4,000 to 6,000 metres below sea level

Only the deepest known areas of the ocean, the trenches, are past this mark.

It is cold (about one degree), dark, lonely, and the pressure is enormous—it’s enough to crush a polystyrene cup to about one third its normal size.

Big muscles and dense bone may be preferable on land but that doesn’t work well down here; most creatures are soft and gelatinous.

They don’t come much squishier than a sea cucumber.

Sea cucumbers (also known as holothuroids) are an incredibly varied group of animals.

While some species are swimmers, they are typically found on the ocean floor hoovering up the detritus.

‘Marine snow’, as it is known, is made up of the decaying remains of animals that have died above and slowly drifted down to the bottom.

This provides the nutrients needed to sustain life down here and sea cucumbers are an essential part of putting those nutrients back into the food chain.

You may think of octopuses as tropical animals, but they are down here too.

However, unlike their shallow-water relatives, the cirrate octopods have fins off their bodies.

The resemblance to a certain flying elephant has led to some members of this group being known as dumbo octopuses.

They even flap these ‘ears’ while they swim.

Possibly because it is so dark and there aren’t many large predators, cirrate octopods are able to survive in the depths without the usual inky defense mechanism found in other cephalopods (squid, cuttlefish, and the like).

So, there are some benefits to life in almost total isolation—does make it difficult to find something to eat though.

While there may not be giant toothed monsters down this far there are fish that have some special adaptations to life in the deep.

The Bony-eared Assfish has a tapered flabby body, small eyes, and the unique claim-to-fame of having the smallest brain-to-body ratio of any vertebrate.

It takes a lot of energy to grow eyes and they are not much use when there is no light to see with.

Animals like the Shortarse Feelerfish (yes, that is its real name) and other tripod fish have all but done away with eyes (but you can still see them if you look closely).

Tripod fish make up for their poor vision by using extended pectoral fins that reach outwards to detect vibrations of approaching danger.

It also takes a lot of energy to swim, so tripod fish have come up with a way to avoid it.

They prop themselves up on their pelvic and tail fins and point into the current, allowing it to bring food to their open mouths.

The research has been made possible through a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.