Anne Bermingham, a scientific pioneer of radiocarbon dating

Meet the woman who called time on discrimination in the public service to establish Australia’s first radiocarbon dating lab.

Uncovering the stories of pioneering women from the Museums Victoria Archives.

Anne Bermingham led Australia’s first foray into radiocarbon dating, but her successes were hard-won.

She battled gender discrimination from the start of her scientific career and was constantly under pressure to deliver results, despite a lack of funding and resources.

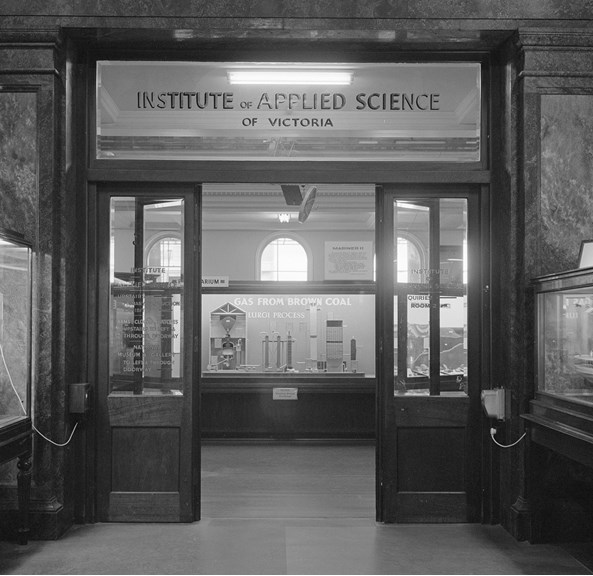

Anne joined the Museum of Applied Science (which later became Museums Victoria) in September 1952, with a degree in chemistry from the University of Melbourne and a decade of industry experience.

The 27-year-old was better qualified than the other candidates, including five men, but her pay didn’t reflect that.

Anne was instead classified at the lower level of ‘Class C1 (Female)’.

‘Although the position was advertised at the higher classification (Class C2) the Board held that this would apply only to a male,’ wrote the museum’s director at the time, Dr CM Focken.

Public service roles were then described by gender—something Anne later took issue with, in a letter to The Age.

‘Sir, - Since the days when I first learned that boy public servants were different to girl public servants, I have searched the State legislation to discover why it should be important in service employment and why it is more important in some areas than others.'Anne Bermingham, The Age, 7 August 1972

Anne successfully argued for a pay rise when she was tasked with establishing Australia’s first Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory.

A new venture

Radiocarbon dating is a method used to date organic material, like charcoal, bones or fossils, by measuring their content of carbon-14—it had been invented by American physical chemist Willard Libby eight years earlier.

Australian material had to be sent overseas to be dated, but the museum wanted to set up a local lab to take advantage of the new technology.

‘There is tremendous pressure here to get the dating service going; this is coming from people with samples, but mainly from the museum’s Trustees, who can’t wait to see the thing working,’ Anne wrote in February 1955.

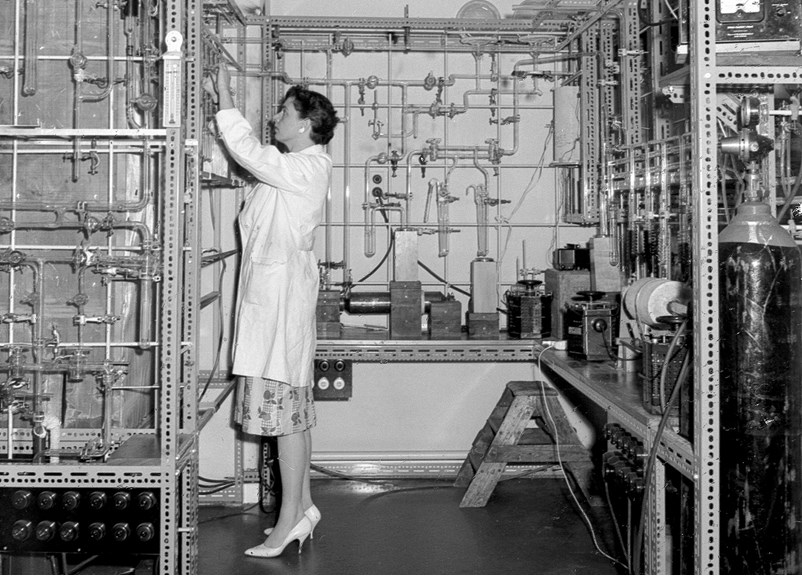

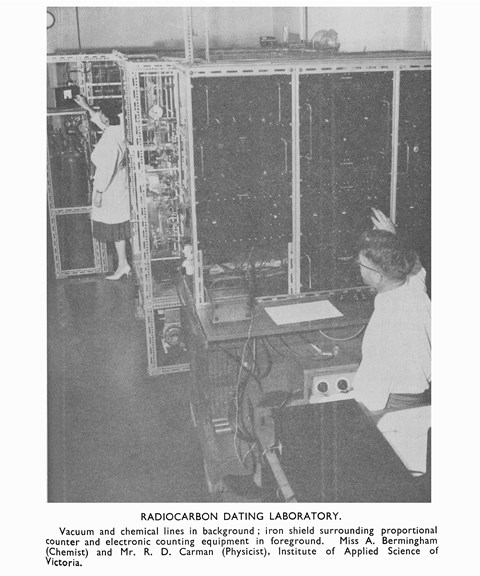

Her job was to set up and run the laboratory, which included designing and constructing equipment, without the assistance of an electronics expert.

A museum report from the time said Anne, ‘Set about this difficult task enthusiastically, and has displayed considerable all-round ability and creditably surmounted the many difficulties that arose in this new application of science’.

In 1956, having secured an English-Speaking Union Travelling Scholarship, Anne embarked on a seven-month tour of dating facilities in the UK, Europe and USA.

‘En route to the United Kingdom and Europe I hope to visit the United States of America, where most of the important radiocarbon dating laboratories are, and where the first world conference on radiocarbon dating will be held from October 1st - 4th, 1956,’ Anne wrote in a memo to the Public Service Board in June.

This was an ideal research opportunity, but the museum was unable to find someone to manage the lab and it had to be closed during her absence.

On her return, Anne relocated the lab to a new home.

‘I now have a much bigger and more convenient laboratory, but it has taken quite some time to construct and furnish the new laboratory, and, of course I have had to rebuild all the apparatus to fit into the new surroundings which has meant repeating such a lot of work. I am very impatient to get going on some samples so the shift has been rather frustrating,’ Anne wrote in December 1958.

‘However, I now have an assistant to look after the electronics side of things, which is a big help. If we do not strike too many problems I will begin dating about the middle of 1959.’

Melbourne’s Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory opened to the public in 1961, but Anne had to periodically suspend dating because of various equipment and electronic faults that cropped up in its first years of operation.

‘Despite all these set-backs, many hundreds of counting runs have been made, but it has been considered advisable to release only eight dates to clients. Consequently, there is a large back-log of samples awaiting determination,’ wrote the museum’s chairman FG Thorpe in May 1964.

Anne persevered, and the lab published its first dates in 1965.

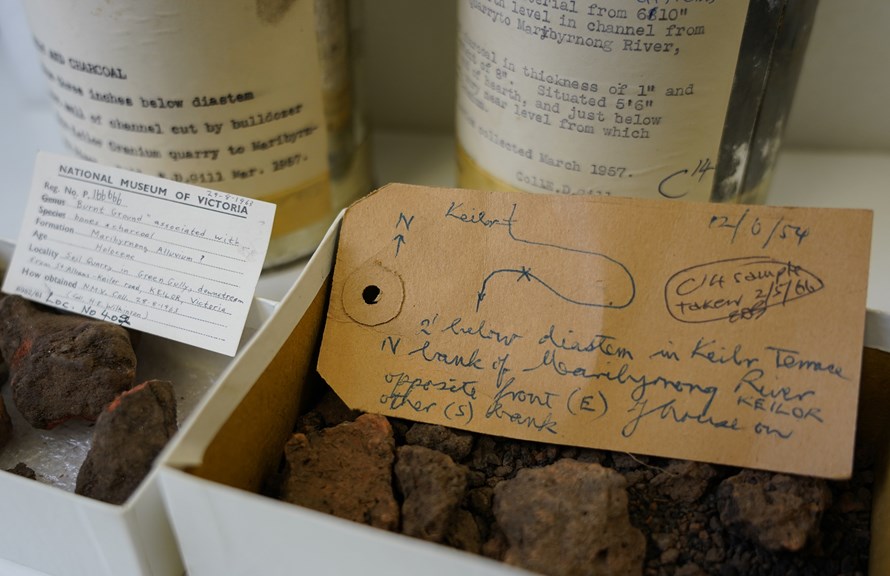

Collecting the past

At the same time, Anne was developing a keen interest in archaeology—so much so, that she was granted an honorary membership in the Archaeological Society in 1965.

It was an achievement that drew the attention of the museum’s chairman of the Trustees.

‘It has become increasingly clear from a succession of Director’s reports that the Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory has been carried through to effective operation, after a series of difficulties and reverses which would have disheartened many scientists in your position.

‘The Trustees are unanimous in expressing their thanks to you for all your devoted and efficient work you have put into the task, and assure you of their wish to give you full support in further developing the laboratory and easing the work load on those concerned,’ the chairman AL Read wrote in a letter to Anne in November 1965.

Anne’s work on archaeological digs was instrumental in establishing a timeline for Aboriginal occupation in Australia, including an expedition at Tasmania’s Rocky Cape in 1967.

It didn't last, though.

End of the road

The Trustees made the decision to close Melbourne’s Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory at the end of 1970.

By this stage much of the lab’s equipment needed to be updated or replaced and it had not turned a profit, as the museum’s Trustees had hoped.

‘It was becoming clear that economic operation was an illusion and could only be a research asset requiring typical research subsidy,’ wrote the museum’s director RH Fowler.

Anne was the only person to see it through its entire 17-year history and was devastated by the news—she even tried to have the decision overturned.

‘The interest in, and demand for, this work is unlimited…there is not and has never been a commercial application for the radiocarbon dating method.’Anne Bermingham

‘Miss Bermingham appeared to become perhaps too dedicated to a project which was necessarily predominantly her own, and to her lasting credit she poured effort and skill into it generously, probably excessively,’ observed Mr Fowler.

Anne stayed on at the museum until her position was made redundant in February 1974, after 21 years of service.

Anne was quickly redeployed to the newly-formed Victorian Arts Ministry, where she became the state’s Scientific Conservation Officer.

Decades later though, Anne’s work at the Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory is still being studied.

Dr Rebekah Kurpiel from the Department of Archaeology at La Trobe University has been working with Aboriginal Victoria to verify radiocarbon dates of artefacts found in Victoria.

‘Although improvements in analytical techniques have been substantial since Anne’s lab was operating, some of the dates from that time are all we have for a number of highly significant Aboriginal places in Victoria, so they still contribute much to our understanding of Victoria’s past,’ she says.