Aunty Jennine’s Gift Giving

During Melbourne’s first COVID-19 lockdown, proud Willum Warrain Elder and Yaran woman Aunty Jennine Armistead (Aunty Jen) brightened the day of people in her neighbourhood by offering cuttings from her garden and handwoven baskets outside her Frankston home.

‘I used to stand out the front doing the garden and you’d see people walking past while we were all closed down,’ Aunty Jen recalls. ‘And the sad look on their faces. Even though you can see a person’s eyes, can see a person smiling … you know that person’s not happy. And I thought, what can I do?’

Aunty Jen placed an old bookcase beneath her letterbox with a sign saying: FREE. Something to bring a smile to your face in such trying times. Every night she would pile it with plants.

‘We have whatever I could dig out of my garden,’ she says. ‘Irises, spider plants, succulents—whatever had a root on it came out.’

The venture was an instant success. Only one or two cuttings would be left when Aunty Jen checked later that afternoon. Soon other people started contributing, leaving new plants in the place of old ones. In a matter of weeks, a revolving neighbourhood nursery was in full flourish outside Aunty Jen’s house. The enthusiasm was a welcome response. When Aunty Jen moved to Victoria from the Northern Territory in the 1980s, she found Victorians mostly kept to themselves.

'I come from desert country up there, Tennant Creek and Darwin. And it’s a different sort of lifestyle […] So coming down here to Victoria was a big learning curve because neighbours don’t speak to neighbours. […] Where I come from, you know the person who lives five miles out of town, you know everybody…'Aunty Jen

Encouraged by the positive response to the plant cuttings, Aunty Jen came up with another idea to reach out to neighbours during COVID-19.

‘I had a lot of weaved baskets,’ she says. ‘And I thought, well, I might give them away. So, I put a table out and they all went!’

Aunty Jen is a talented and prolific basket-weaver. Many of her creations were woven at the Women’s Group meetings at Willum Warrain Aboriginal Association in Hastings and are made from common reed.

‘But I call it emu grass because the feathers look like emu feathers.’ Aunty Jen indicates the fringing on some of the baskets. ‘That’s just decoration, but the plain ones underneath, they have uses – you can make ones to catch yabbies in, you make fish baskets, and they’re all different shapes and sizes.’

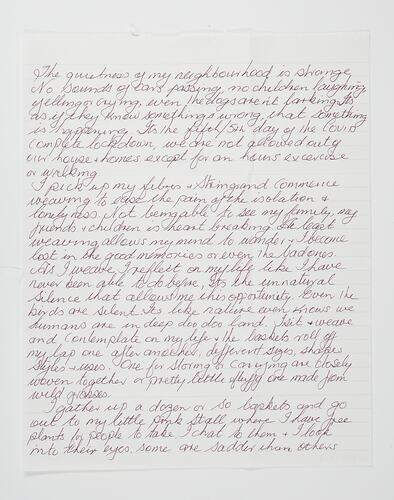

For Aunty Jen, giving away her handwoven baskets became an important way to channel her own thoughts and connect with her community. In a diary entry on Day 5 of Victoria’s second lockdown in August 2020, she reflected: ‘I pick up my fibres and strings and commence weaving to ease the pain of the solitude. Not being able to see my family, my friends and children is heart breaking. At least weaving allows my mind to wander and I become lost in good memories, or even the bad ones. As I weave I reflect on my life like I have never been able to do before, it's the unnatural silence that allows me this opportunity.

I gather up my dozen or so baskets and go out to my little stall where I have free plants for people to take. I chat to them and I look into their eyes, and some are sadder than others – they say they are almost at breaking point. I offer them a hug and give them a basket that I have made especially for them.

Every stitch is a memory of my youth and old age, every stitch is a memory of happiness or pain that makes up my story.’

It’s hard not to be awed by Aunty Jen’s generosity. But for her, sharing with others is not something that merely emerged from the pandemic; it is deeply embedded in her upbringing and values:

'In our culture, sharing is very important. It’s not, That’s mine, you’re getting nothing. In the Indigenous culture, you share. And you must share.'Aunty Jen

The acts of sharing and giving, of communities uniting to support one another, are undoubtedly some of the benefits to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet for the Aboriginal community of Willum Warrain, this is what they have always done. Aunty Jen is a respected Elder there, and joining Willum Warrain was a turning point.

‘I’d been lost for a long time, not belonging anywhere, having been taken out of the desert and brought down here,’ she remembers. ‘And walking in through Willum Warrain gates, it was like, Thank god I'm home. I automatically had a sense of belonging.’

Willum Warrain, which translates to “home by the sea” in the Boon Wurrung language by Westernport, is an Aboriginal Community-controlled organisation that provides a safe cultural space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the Mornington Peninsula. It officially opened in 2014 but had been in the works under various other names and operations since the late eighties.

Anne Benton – Aunty Jen’s friend and fellow member of Willum Warrain – is non-Indigenous, but is connected to the association through kinship ties and is also a prolific basket weaver. ‘I'm grateful to Anne because Anne told me about Willum’, reflects Aunty Jen. ‘She knew I was a lost soul, and suggested that perhaps it would do me the world of good to go out there. For that I will be forever grateful.’

Anne’s husband, Uncle Peter Aldenhoven, is a Willum Warrain Elder and the Executive Officer of Men’s Business.

‘I've sort of been in the background,’ Anne says. ‘Keeping the home fires burning while [Peter has] been developing Willum Warrain […] Initially it was an idea, and then a committee, and then a group of people working together. And it’s grown from there.’

As Uncle Peter emphasises, echoing Aunty Jen’s sentiments, Willum Warrain has a huge ‘significance to mob down on the Mornington Peninsula’.

‘What’s unusual about where we live is that there’s very few local people, Bunurong or Boon Wurrung people residing on the Peninsula,’ he says. ‘And probably half of the people there are Koorie, from elsewhere in Victoria, or Aboriginal Diaspora from all over Australia.’

'When you’re away from Country and kin, they’re the twin anchors of being an Aboriginal person, and you are lost. You really feel that disconnect, and so that’s one aspect, I think, to Willum Warrain and its importance for Aboriginal people down our way, but also as a place of hope and healing.'Uncle Peter

Uncle Peter is, in Aunty Jen’s words, ‘the Elder’s Elder out at Willum’. He is a proud descendent of the Quandamooka peoples—more particularly, the Nughi clan from Moorgumpin (Moreton Island) in Queensland. Growing up away from his Aboriginal family, he appreciates how vital it is for Aboriginal people to have access to community and culture.

‘I was adopted out at birth and didn’t reconnect with my Aboriginal mother until the age of 34,’ he says. ‘I'm 63 now. It’s a big journey of identity. For a lot of mob who don’t grow up Aboriginal, you know, that deep existential question is always there. We just try and help people when they come to Willum Warrain, and we just welcome them. We just say, Come in.’

Willum Warrain, which has over 450 Aboriginal members, is gaining more and more traction. Its growth in past years has given it the resources to provide a range of programs for its Aboriginal community members, including a Women’s Group, a Men’s Group, a Deadly Kids Group, a Bush Play Group (for younger kids and toddlers) and a Gardening Group (open to non-Indigenous members as well). Another beautiful tradition, led by Bunurong Elders, is the Welcome to Country ceremony for babies, where children are painted in ochre and given an Aboriginal name.

The programs foster ‘a sense of belonging and a sense of community’, says Aunty Jen. ‘And we work as a community to help each other. If I hear of someone that’s in trouble, or something, I talk to the Women’s Group and we see how we can help. If Peter hears something, a kid of someone’s needing help, the Men’s Group become involved.’

For Taneisha Webster, proud Wathaurong woman and the Executive Officer of Women’s Business, having a space exclusively for Aboriginal women is essential. As she comments in Mornington Peninsula magazine, ‘Willum Warrain’s sacred space for women and children to gather safely not only builds female-to-female bonds, but also offers a place for all women to sit in their Aboriginal identity.’

This is especially important, Taneisha continues, so that they can experience ‘a cultural engagement which Aboriginal women may not be getting anywhere else.’

Feeling culturally strong and forming positive cultural memories also contributes considerably to the mental and physical health of Willum Warrain women. But of course, due to COVID-19 restrictions, the group meetings and programs could no longer go ahead, and Willum Warrain Gathering Place had to close.

‘Which was pretty devastating for mob,’ adds Uncle Peter. ‘Covid has been incredibly impactful for all of society, but for Aboriginal people with that need for being together and to engage in cultural practice, to be in the bush, to be on Country, I think it’s brought a set of particular challenges.’

Although their doors were closed, the Willum Warrain staff continued to work tirelessly throughout Victoria’s lockdowns to support community.

‘We were very concerned that our Elders, many of them are quite socially isolated and have complex health challenges,’ Uncle Peter says. ‘We wanted to provide them with a meal each week, a cooked meal, but also basic groceries to reduce their need to go out.’

During lockdown, Willum Warrain were able to employ some extra staff through the Working for Victoria scheme to help with food deliveries and drop offs for Elders and vulnerable community members. With Aboriginal people aged over sixty-five being particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, Willum Warrain made a concerted effort to frequently reach out.

‘Covid could have cut an absolute swathe through Aboriginal mobs,’ remarks Uncle Peter. ‘It would just be horrific. And even in Victoria, hardly any Aboriginal people got Covid, and that’s because we took care of each other and we really listened to the messaging.’

‘I was always being rung up,’ says Aunty Jen. ‘Have you got anything, do you need anything? […] And I did the same for my neighbours, even though they’re not Indigenous.’

And as Uncle Peter points out, it is not a new experience for Aboriginal people to be affected by disease brought from other countries:

'Us Aboriginal mob, we were devastated by smallpox when the First Fleet arrived. Some ethnologists believe that two thirds of Aboriginal people on the eastern seaboard died before they saw a white person. So, we've faced serious catastrophic pandemics and survived them and I've got a real pride in what our local community’s done…'Uncle Peter

Despite the difficulties of not being able to gather together, the strength and resilience of the Willum Warrain community shines through in how they bound together to respond to COVID-19.

And for Aunty Jen, offering up a little bit of her garden, of her home soil, was something simple she could do to cheer people up.

‘I do like messing around in the soil a lot,’ she laughs. ‘I like getting my feet and my hands dirty, and I like touching soil.’

So strong is her connection to Willum Warrain that Aunty Jen has taken to carrying a tube of Willum Warrain soil with her whenever she travels. This tradition has since been integrated into the Welcome Baby to Country and naming ceremonies at Willum Warrain—to gift kids the soil of their Country.

‘So that no matter where you go in Australia or in the world, you have got your Country in your hands,’ says Aunty Jen. ‘And that means a hell of a lot. And if you get really lonely, you take the cork out and you just rub it between your fingers and you’d be surprised how soothing that is, to have your Country with you.’

For many people, lockdown living brought a shared resentment of being “stuck” at home and unable to travel. Yet Aunty Jen’s perspective is a humbling reminder of just how comforting, how strengthening the concept of home can be. The connection to home and culture is something Elders wish to impart to new generations of Aboriginal kids at Willum Warrain.

‘A lot of the parents say [Willum Warrain] is a high, high priority for us because we want our kids growing up strong in culture like we never did. Some of them drive 20, 30 kms to Willum Warrain on a Thursday just so their kids can get that exposure to culture.’

'Our kids are our future, and if we don’t teach our kids, we’re lost'Aunty Jen

‘Colonisation, invasion has disrupted the transmission of knowledge,’ says Uncle Peter. ‘And what we’re trying to do at Willum Warrain is to retrieve or reanimate that knowledge. […] So having Aunty Jen giving that beautiful gift of a piece of Country from Willum Warrain […] to these kids, and a Bunurong Elder bestowing a Country name on them, we feel that they’re going to have that core identity in place right from the start.’

Certainly Aunty Jen’s presence at Willum Warrain is invaluable to many.

‘I know a lot of women derive considerable strength from you, Aunty,’ Uncle Peter says to Aunty Jen. ‘And, you know, the traditional structures around leadership aren’t there, so we’re sort of creating it as we go. But part of your finding your way home or belonging was in a leadership role for our women, children and families.’

And luckily for both the Willum Warrain community and the broader one on the Mornington Peninsula, Aunty Jen isn’t going anywhere.

‘Having been out to Willum, I now feel at home,’ she affirms. ‘So whatever happens, I will stay here. […] It’s my Country. You know, my home base. I may not be a woman from here, but my spirit and my soul are from here.’

This story is based on an oral history interview that was conducted between Aunty Jennine Armistead, Uncle Peter Aldenhoven, Anne Benton and Museums Victoria Curator Catherine Forge on 2nd December 2020. With the support of the Office for Suburban Development, this interview and accompanying photographs have been acquired into Museum Victoria’s State Collection for posterity. In February 2021, Aunty Jennine also generously donated two weaved baskets to Museums Victoria’s State Collection. A Willum Warrain T-Shirt was also acquired. These baskets, photographs, T-Shirt and oral history interview will provide a lasting reminder of the community support activities of Willum Warrain members during COVID-19, as well as the importance of place, connection to Country and the vital role of First Peoples cultural knowledge and customs during the pandemic, and always.