Marvellous Melbourne

By world standards, Melbourne is a young city but it has layers of history.

Bluestone and concrete, paint and neon, Victorian-ornate and sheet-glass — all cram into the cross-hatched canyons that are Melbourne's streets and lanes. Here you can discover how each era shaped the city we see today.

European settlement in Melbourne

Melbourne started as an illegal settlement. Despite opposition from the government in Sydney, sheep farmers from Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) crossed Bass Strait in search of new pastures.

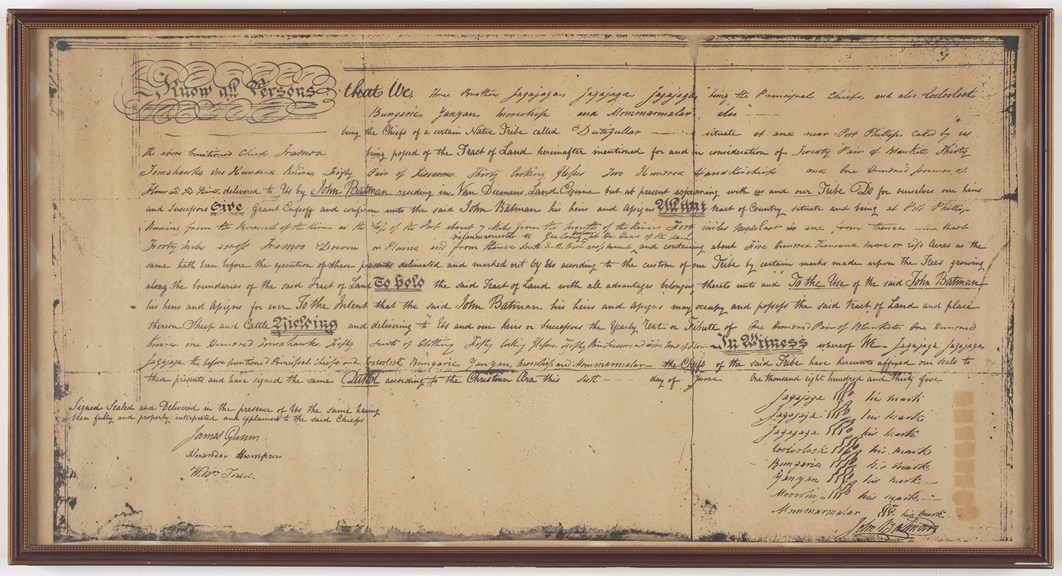

In May 1835, a syndicate led by John Batman explored Port Phillip Bay, looking for suitable sites for a settlement. Batman claimed to have signed a 'treaty' with Indigenous leaders, giving him ownership of almost 250,000 hectares of land in exchange for 20 blankets, 30 tomahawks, 100 knives, 50 pairs of scissors, 30 looking glasses, 200 handkerchiefs, 100 pounds of flour and six shirts. This treaty is the only known land use agreement that attempted to recognise land rights prior to European settlement in Australia.2

What Batman understood to be a transaction of land ownership was actually intended as permission to pass through but not remain. This treaty was refused by the colonial government as it would question the legality of the claim of Australia as Terra Nullius. Three months after the treaty was signed, another syndicate of farmers, led by John Pascoe Fawkner, entered the Yarra River aboard the sailing ship Enterprize, establishing the first permanent settlement.

New South Wales Governor Richard Bourke declared Batman's treaty illegal and the settlers to be trespassers, but within two years, more than 350 people and 55,000 sheep had landed, and the squatters were establishing large wool-growing properties in the district. Bourke was forced to accept the rapidly growing township. In 1837 he sent troopers from Sydney to establish order in the new township. Interaction between settlers and First Peoples was officially discouraged. Corroborees, which often attracted many white onlookers, were outlawed. Mounted troopers patrolled the edge of town.

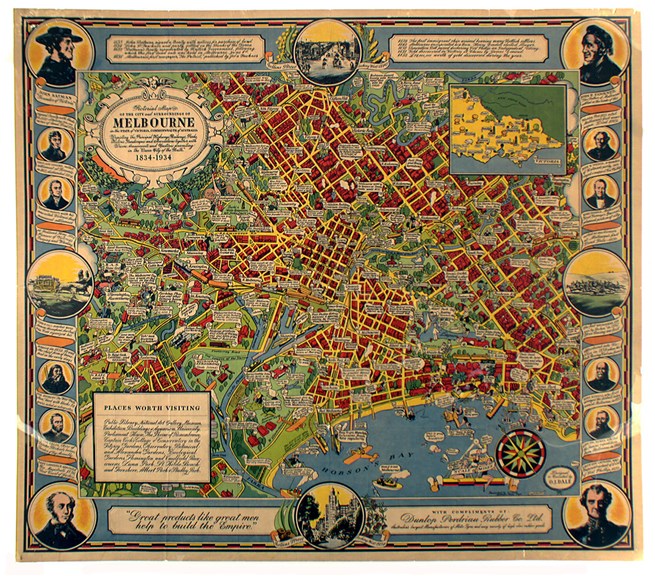

In 1837, Bourke selected Robert Hoddle, the senior surveyor from Sydney, to take up the chain and circumferenter (surveyor's compass) for the government. On 4 March, Hoddle and Bourke rode over the area on horseback and traced the general outline of the township. On 7 March, Bourke directed that the town be laid out, and on the 9 March the governor named the settlement 'Melbourne' after the British prime minister of the day. By the end of April, Hoddle's plan of Melbourne was lodged at the government survey office in Sydney.3

Not all have agreed that the plan of Melbourne is actually the work of Robert Hoddle. Governor Bourke, Robert Russell and William Lonsdale have also been credited with Melbourne's grid design. Whatever the verdict, the 1837 grid of wide and narrow streets remains Melbourne's dominating historic memento of European settlement.

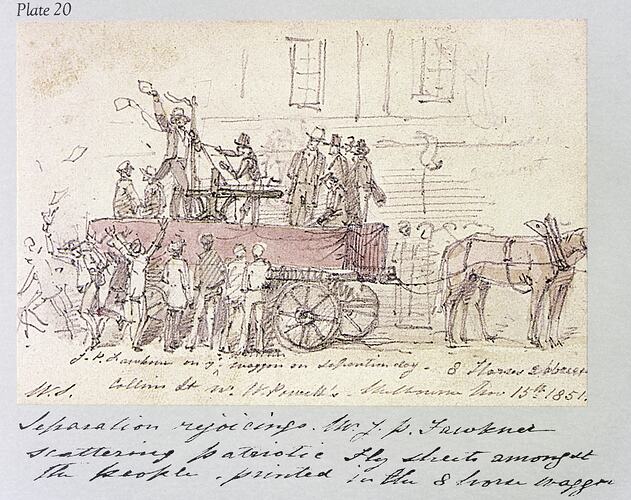

The colony of Port Phillip petitions to separate from New South Wales

A Separation Association formed in 1840 and drafted the first petition to separate Port Phillip from New South Wales in the same year. Six years later, although the movement had been gaining popularity, there was no formal change until Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe wrote a letter to the English government, arguing for representation in parliament. A Separation Bill was passed by British Parliament and signed by Queen Victoria in 1850, but the news took 14 weeks to reach Australia. The Bill was finally enacted in New South Wales Legislative Council in 1851.4

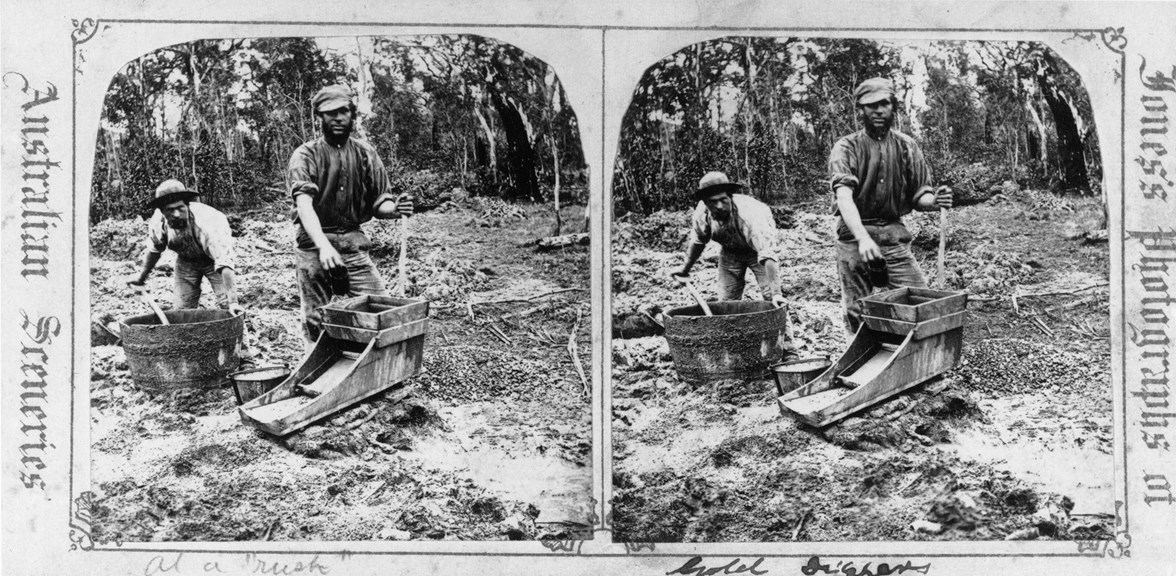

Gold discovered in Victoria

Immigrants leaving Britain in 1852 bought more tickets to Melbourne than to any other destination in the world. The new arrivals chased a single dream — gold. After the discovery of gold near Clunes in 1851, thousands arrived daily. Lodging houses and hotels were packed to bursting point and makeshift houses of iron, timber and canvas sprang up on the city's edge. Sudden wealth transformed a small port town into a frantic world centre: the wharves were constantly jammed with shipping, cargo and migrants disembarking.

The combination of Melbourne’s exponentially increasing population and the loss of police force to the diggings created chaos. The authorities hastily recruited a police force, recruiting young gentlemen as officer cadets as well as 53 London bobbies. Mounted on horseback and armed with sabres and carbines, they patrolled the city day and night.

Society went wild with its new wealth. Diggers drank champagne from buckets and Irish maids paraded in silks and diamonds. Stories circulated of successful diggers lighting cigars with banknotes. One hotel maid was rumoured to have made a fortune by collecting gold sweepings off the carpets. Although most would return from the goldfields penniless and exhausted, fantastic stories continued to offer hope of fortune.

The sudden and extreme human interference with the environment caused rains to turn dirt roads into knee-deep mud and main streets to raging rivers. In summer, hot winds whipped up dust storms. People tied veils around their heads to protect their eyes and nostrils. Water carts dampened the streets to keep down the dust.

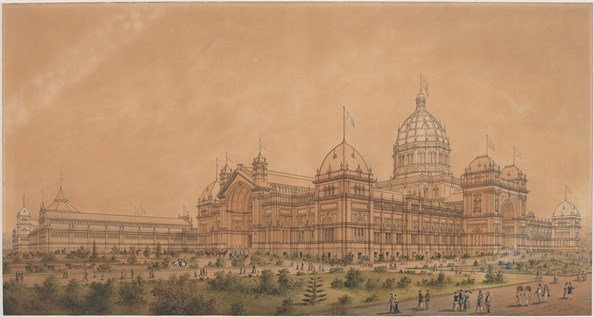

Archibald Michie remembered the Melbourne of 1852 as little more than 'a very inferior English town'. Only eight years later, he was astounded by Melbourne's transformation into 'a great city, as comfortable, as elegant, as luxurious as any place'. The gold rush saw Melbourne transform from a muddy frontier town to a solid city of spires and domes.

Local architects, such as JJ Clark, Joseph Reed, Leonard Terry and Lloyd Tayler, showed the same devotion to Italian classicism as their contemporaries in Britain. Banks, offices and clubs were reinterpretations of villas, temples and palaces. New civic buildings — the Customs House, Post Office, Treasury and Parliament — publicly displayed state power. The wealth from the gold rush also contributed to the construction of many schools, churches, galleries, the State Library, and Flinders Street Station (the first railway station in Australia).

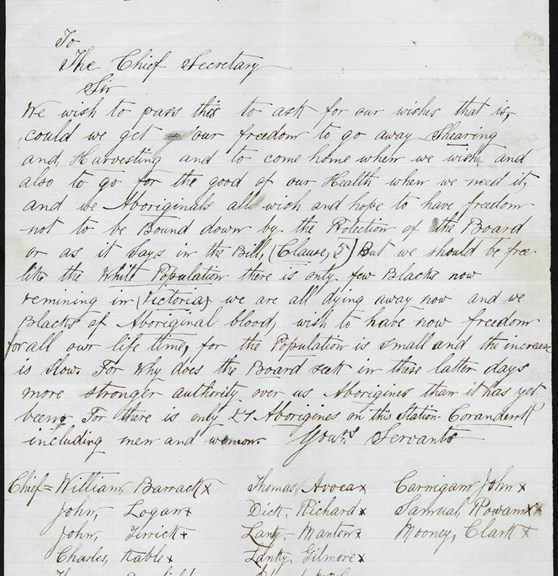

Coranderrk

After decades of being forced off their own land, and the loss of food sources as a result of farming, the Wurundjeri people, led by William Barak petitioned the government for their own land. Coranderrk Reserve was created by Protector William Thomas in 1863 on the land of the Wurundjeri-balluk clan, covering 4850 acres between the Yarra River, Badger Creek, Watts River, and Mount Riddell.

It took only a decade for Coranderrk Mission to become a self-sufficient village. In 1886 a government Act forced any individual of "mixed descent" under the age of 35 to move out of Coranderrk, thus ageing the population significantly. This, and the termination of government funding resulted in the closure of Coranderrk in 1924. Most of the residents were moved to Lake Tyers Mission.5

The changing course of the Yarra

Melbourne's Yarra river flows from Mt Baw Baw for 242 kilometers, and is called Birrarung (river of mists and shadows) by the Wurundjeri people. The Yarra gets its name from a misinterpretation of the Wurundjeri phrase Yarro Yarro meaning 'it flows', heard when John Wedge asked the locals about the falls at the lower end of the river. Clear at the time of European settlement, the water has muddied due to land clearing, and easily eroded clay soils but although the water looks muddy, it is one of the cleanest capital city rivers in the world.6

Frequent flooding was common in the Yarra; the first recorded flood was in 1839, and the most severe in 1891 caused the river to rise 14 meters higher than normal. Starting in 1879, the Yarra River’s course was altered to mitigate the frequent flooding and to straighten it to become parallel with Melbourne’s city grid. The Falls (Yarro Yarro), which separated salt and fresh water was also removed. To reduce travel time, the Coode Canal was dredged, in the process creating Victoria Harbour and Victoria Dock.7

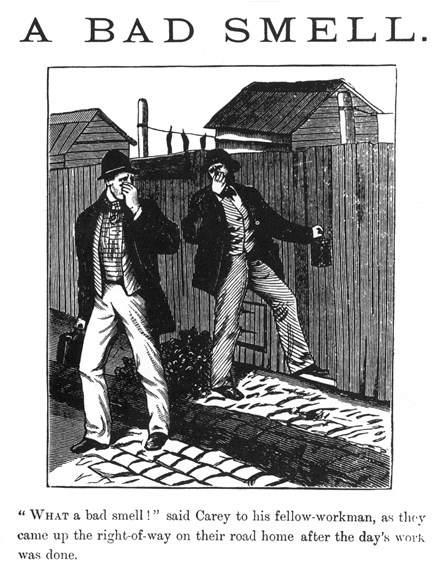

"Smellbourne"

In the 1880s, Melbourne had as much stench as style. Scraps, slops, urine and faeces flowed through the streets in open gutters. Diseases such as diphtheria and typhoid flourished.

Believing that bad air from low-lying areas would make them ill, wealthier residents built on higher ground and took to using smelling salts. Following a public outcry and numerous government inquiries, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works was formed in 1891 to build an underground sewerage system.

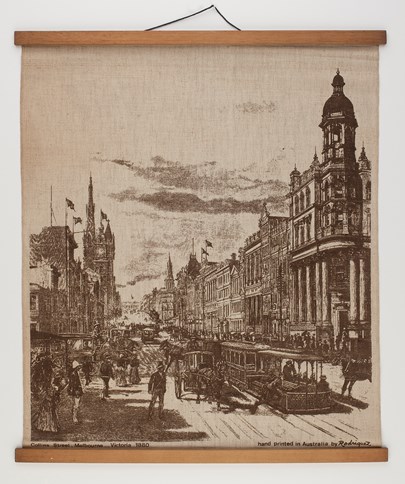

Melbourne's population reaches half a million

The city's facilities simply couldn't cope with the rapid rise in population. Visitors to Melbourne in the 1880s were amazed. Here in the Southern Hemisphere was a city larger than most European capitals. In just a decade the population had doubled, racing to half-a-million. Citizens strutted the streets, bursting with pride as their city boomed.

While Sydney was seen as slow and steady, Melbourne was fast and reckless. Ornate office buildings up to 12 storeys high rivalled those of New York, London and Chicago. Money was poured into lavishly decorated banks, hotels and coffee palaces. Towers, spires, domes and turrets reached to the skies.

Melbourne's iconic cast iron lace

Melbourne has more decorative cast iron than any other city in the world. By the 1880s it symbolised the city's brash image. Virtually every new balcony and verandah was draped in an 'iron petticoat'.

John Ruskin, a noted English architecture critic, derided cast iron as 'cheap and vulgar'. Melbourne could not have cared less. Over 40 local foundries were kept busy, melting and casting pig-iron bars that arrived as ship's ballast. By 1900, the foundries had registered 161 different designs.

The telephone

In 1880, Melbourne became host to the first telephone exchange in Australia. When it began, the subscribers filled only one page, but by 1887 a dozen women were answering a total of 8000 calls every day. The earliest subscribers were mostly wealthy – banks, solicitors, insurance companies, auctioneers, printers, importers, brokers, and merchants.

The new invention was to have far-reaching implications for the shape of the city. Taller buildings appeared, made possible by easy communication between floors. Most striking was the forest of poles and wires that spread along the city streets. But the army of errand boys and letter carriers who had scurried between city offices disappeared — rendered obsolete by the new invention.

Trams

The first cable tram in Victoria operated along Flinders Street to Richmond in 1885. Within five years, trams were ferrying people between the city and inner suburbs along 65 kilometres of tram tracks. The driving power for the underground cables came from engine-houses positioned at intervals along each route.

By 1916, these trams were carrying more than one hundred million passengers a year to and from the inner and middle suburbs, at speeds averaging 15 kilometres an hour, including stops. Major shopping strips such as Sydney Road, Puckle Street, Glenferrie Road and Chapel Street boomed.

The first electric tramway opened in 1906, and the gradual electrification of the entire tram system occurred during the 1920s and 1930s. The last cable tram — running along Bourke Street to Clifton Hill — ceased operation in 1940.

While many cities in the world, including most Australian capitals, were scrapping their tram systems from the 1950s, Melbourne not only retained its trams but continued to update the fleet. Melbourne's tracks and tramcars were in good order and the city is well-suited to trams, being relatively flat with wide streets. That no-one in authority ever made the order to get rid of them was one of the better non-decisions ever made by bureaucrats.

Trams are here to stay — although the familiar sound of 'Tickets please' disappeared with conductors in 1998.

Depression in Melbourne

By 1891 the high times were coming to an end. Banks closed their doors, companies went bankrupt, and a speculative boom in property led to a banking crisis in 1893. Melbourne was the world epicentre of the bust.More than a third of bread-winners were unemployed, one in ten houses was repossessed, and without poor laws many became destitute. It was a dramatic fall, and a far more sober and cautious Melbourne faced the new century.

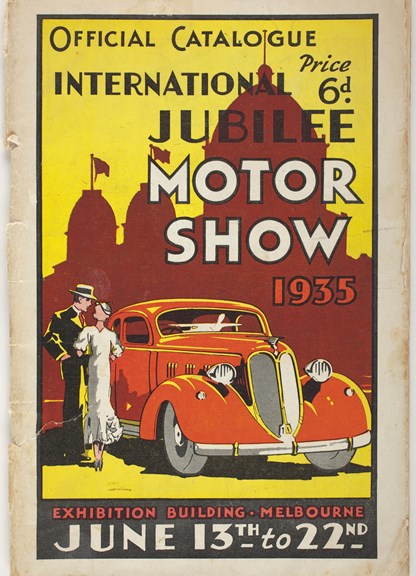

The coming of the motor car

Motorised vehicles made their first appearance in Melbourne about 1900. At first they were praised for being faster and cleaner than horses. However, their noise, speed and fumes frightened horses and left pedestrians ducking for cover. People complained of 'road hogs' who recklessly sped through the streets endangering all in their path.

To control the motorised horde, in 1916 Melbourne City Council imposed new restrictions. Vehicles had to travel on the left-hand side of the road in not more than two lanes. When stopping, a hand or a whip had to be raised. In the following years hand signals for turning were imposed, along with time restrictions on parking.

Initially considered a toy for the wealthy, the ownership of motor vehicles increased most markedly after World War I. Registrations of motor cars, trucks and cycles doubled between 1917 and 1922, when 44,750 were registered.

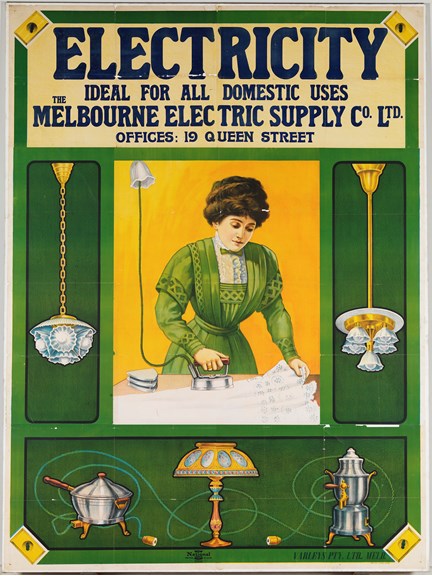

Powered city

Melbourne had become a wired city by 1910. Networks of pipes and cables coursed underground, drooped across streets and snaked up buildings. Increasingly the city was seen as a machine, tended by its engineers.

The new systems changed the way the city worked. Stockbrokers and lawyers could telephone their clients and clerks were elevated to their offices in lifts — Melbourne already had over 1000 by 1907.

Under the clocks

For more than a century the grand Edwardian baroque building of Flinders Street Station has dominated Melbourne's southern boundary. Trains had been arriving at the site since 1854, but the red brick and golden cream stucco design was selected by an architectural competition held in 1902, and constructed between 1905 and 1910. Longer than a city block, it boasts grand archways and an expansive ballroom. The clocks above the entrance to this Edwardian baroque masterpiece acted as pacesetters for the tens of thousands of people who passed beneath daily. Meeting 'under the clocks' is a Melbourne habit, and the building arguably remains the city's principal landmark.

As well as work, entertainment drew people to the city. About ten cinemas were operating by 1913, mostly in Bourke Street, and Melburnians had long enjoyed the footlights of its east end theatre district.

Australia's seat of government moves to Canberra

Melbourne was the seat of government for the Commonwealth of Australia from 1901 to 1927. As a result, Melbourne retained many national institutions in to the twentieth century.

Department stores – a new luxury

Department stores in the 1920s turned shopping into a popular leisure activity for women. Passers-by were enticed by tantalising window displays. Shoppers browsed among arrays of merchandise. Cafeteria dining completed the 'day out'.

Bourke Street was the department store hub. Coles, Myer, Buckley and Nunn, Foy & Gibson, Paynes Bon Marche and Hicks, Atkinson and Sons were all within a short distance of each other.

1923 Police Strike

On the eve of Melbourne's Spring Racing Carnival in November 1923, half the police force went on strike due to suspected government spying. Riots, looting and mayhem followed as race crowds piled into a lawless city. Thousands of volunteer 'special constables' were sworn in to restore order. Many were veterans of World War I. They were identified by badges and armbands. Although the strike was ultimately successful (Victoria Police received a pay increase and pension scheme), about a third of the Victorian police force was dismissed in the course of the strike.

Depression: a city of contrasts

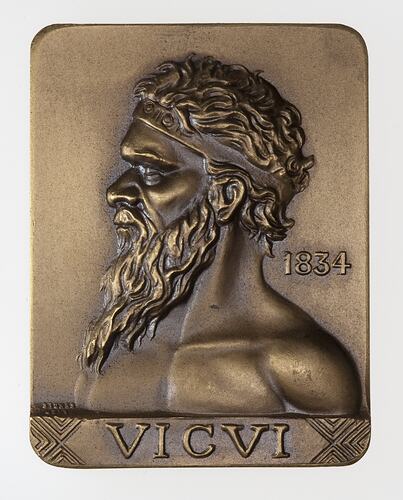

As Melbourne neared its centenary year in 1934, idyllic views across the Yarra River presented a city of 'unrivalled loveliness' in postcards, posters and even rugs. This tranquil image belied what was actually happening in the streets of central Melbourne. The Great Depression had hit hard. One-third of the workforce lost their jobs, and there was little social security. Destitute people wandered the streets, surviving on soup kitchens and the support of fund-starved charities.

The crisis sharpened the divide between the right and the left of politics, and violence frequently followed demonstrations. The rich made the poor angry; the poor frightened the rich. Amidst these tensions, Melbourne endured.

With many rickety buildings deemed a fire hazard and demolished, the city took on a more uniform and permanent appearance. Beside the new buildings, public buildings and churches looked smaller and older.

In 1934, as Melbourne planned to celebrate the centenary of European settlement, it seemed to some that there was little to celebrate.

Perhaps because of such troubles, the organisers of the centenary celebrations tried doubly hard to be positive. The themes of the celebrations were conservative, reflecting the desire of some Melburnians for security in troubled times. The widely promoted image of the 'Garden City' and 'Queen City of the South' emphasised the idea of Melbourne as a very British city, and the transplantation of 'Captain Cook’s Cottage' from Yorkshire to Melbourne underlined the narrative of discovery and triumph. A visit by the Duke of Gloucester, son of the ageing King George V provided a reassuring strengthening of Melbourne's imperial connections.

This imagining of Melbourne's history saw the elevation of John Batman to heroic status, reinvented as a courageous pioneer whose life exemplified the rewards of self-improvement. This ignored Batman's dubious 'treaty' with the Wurundjeri people and the less savoury details of his personal life. This narrative of Melbourne's triumphant past intentionally excluded the living story of the Indigenous peoples' of the Kulin nation.

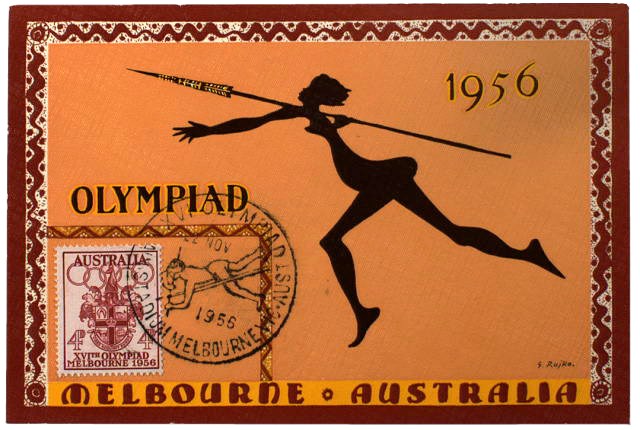

1956 Summer Olympics

The staging of the Olympic Games in Melbourne in 1956 is often viewed as a turning point in the social, cultural and architectural development of the city. Olympic fever enveloped Melbourne and Australia, leaving countless collective memories and arguably a more mature, sophisticated nation. The Olympics was an event of such magnitude in Melbourne that homes became family archives for the ephemera of Olympic experiences and memories.

'Olympomania' spread like wildfire, flooding the market with souvenirs. In their desire to present a uniquely Australian imagery to the international public, designers appropriated Indigenous motifs into both modern and more traditional graphic styles. This practice has resulted in culturally sensitive or secret material being used publically and offensive culturally for the Indigenous peoples that owned these images.

Melbourne was transformed in the years that followed. Buildings grew taller, traffic got thicker, and new immigrants brought new ideas and ways of living. Many old buildings, with their stone gargoyles and cast-iron lacework, tumbled under the wrecker's ball. The central city rang with the din of jackhammers. Glass and steel skyscrapers reached into the air — symbols of enterprise.

Counter-Culture

Melbourne's thriving creative atmosphere has fostered many counter cultures. Pre-cursors to punk, 'sharpies' could be seen around suburbs like Fitzroy in the 70s, and were identified by their haircuts (very short on the top and sides, and long at the back), high-waisted pants, platform shoes, and tight polo shirts or cardigans. Many sharpies were the children of Greek, Yugoslav, Italian, and Maltese migrants and sometimes associated with 'skinheads'. Like skinheads, they were often disaffected youth, and could be violent towards rival groups.

The punk scene that followed was highly creative. The community in this counter culture was welcoming and intellectually stimulating. Many people involved in the punk scene describe its spirit of looking after one another. Melbourne was the thriving hub of punk in Australia, before it grew to other capital cities.

The creativity of the era saw a remarkable boom in the local music industry. Every night of the week corner pubs and hotels shook with the sound of drums and electric guitars, in a time before poker machines became ubiquitous.

Other changes were also taking place in Melbourne’s social life. The 1990s brought in new, relaxed liquor laws that meant that alcohol could be served without food. Melbourne's laneway cafes embraced this change, creating the laneway bar culture that Melburnians now know and love.

References

1 https://aboriginalhistoryofyarra.com.au/

2 https://aboriginalhistoryofyarra.com.au/4-treaty/

3 https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/6775

4 http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/colonial-melbourne/everyday-life/port-phillips-separation

5 https://aboriginalhistoryofyarra.com.au/7-the-protectorate/