The timeless and living art of possum skin cloaks

The First Peoples of south-eastern Australia have been making possum skin cloaks since time immemorial—today the practice is flourishing.

Fishing, birdwatching, parenthood, commutes—these are among the stories told by two new objects in a Melbourne museum which continue a custom practiced in south-eastern Australia since time immemorial.

For tens of thousands of years, possum skin cloaks protected First Peoples from cold and rain, mapped Country, told, and held, stories.

They still do—possum skin cloak making has undergone a revival. Today, the practice is flourishing. And while it is a tradition which connects them to their Ancestors, 21st century community tell stories both timeless and contemporary through their designs.

So, in mid-2019, when one of just a few historic cloaks in the world was placed into storage, the Gunditjmara community of south-western Victoria set about creating two new cloaks to tell their stories.

Historic cloaks are exceedingly rare

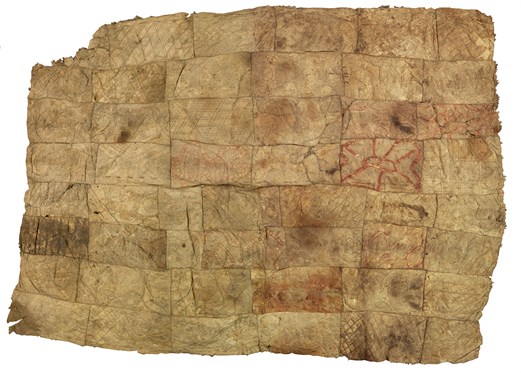

Melbourne Museum is the custodian of two cloaks from the 19th century.

Southeastern Australia Aboriginal Collections senior curator Kimberley Moulton says there may only be three others from the period anywhere in the world.

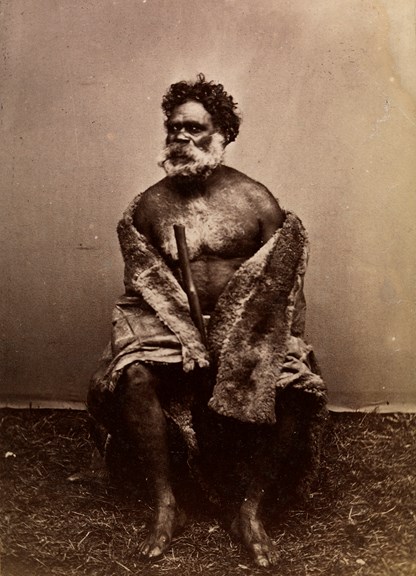

Because, prior to Europeans colonisation, a person’s possum skin cloak was intimately entwined with their life story. From the moment of their birth to their death—and into the afterlife.

'Traditionally ... we would have possum skin cloaks from when we were a baby,' the curator and Yorta Yorta woman says.

'They might’ve been four or five pelts big and then, as you grew, you would add on to that.'

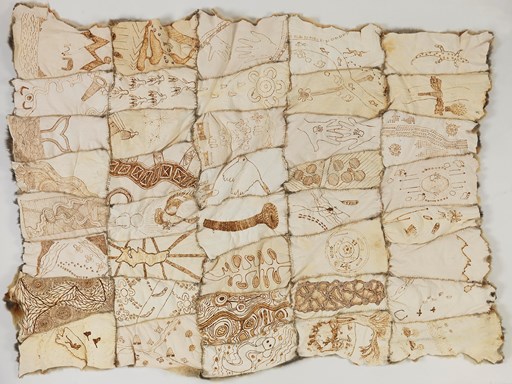

As a cloak grew, designs on its skin-side became more elaborate. Designs carved with bone awl or shell engraver, rubbed with animal fat and coloured with ochre. Designs that chronicled the cloak wearer’s journey, their connection to Country and to family.

In this way, with time, a cloak became more than an item of clothing—it became a 'marker of identity'.

And if possum pelt was the first material object an infant might touch, the luscious fur would also be their last. Traditionally, people were buried in their cloaks.

'The markings were not just pretty patterns, they were deep, meaningful, iconography of Country, of totem and of place.'Kimberley Moulton

The museum’s two historic cloaks were collected from the Yorta Yorta people of north-eastern Victoria in 1853 and the Gunditjmara people at Lake Condah in 1872.

They are the only known surviving cloaks in the world of their time and place.

The Yorta Yorta cloak was on display from 2013. By 2019, the time came for it to be taken into storage for restoration. It was also time for new stories to be told.

So with a smoking ceremony on the last day of May to cleanse the cloak and space, the Lake Condah cloak was brought out of storage and took the Yorta Yorta cloak’s place in public view.

And, alongside the historic, the two recently commissioned cloaks.

These new cloaks tell the contemporary Gunditjmara stories—stories which will be passed on down generations to come.

Diana 'Titta' Secombe saw an eagle

She was standing outside her daughters' home in the western district town of Heywood on the Fitzroy River.

'I asked him to come back and so he circled over the top of me,' she recalls.

'I asked him to take what I had and give me the strength to be here today, because my journey’s not finished.'

The Gunditjmara Elder etched three designs into the new possum skin cloaks.

'There’s one that I did with the eagle over the top and there’s a person standin’ and you can see the dimples in the bum,' she said.

“That’s my journey of when I was going through chemo. I came through it, I survived it.”Aunty Titta

Of course, not everyone does. Many other people and families in Aunty Titta's community have been 'touched by cancer', including the artist’s late mother.

'So I thought I’d put that on the cloak to represent [those] people.'

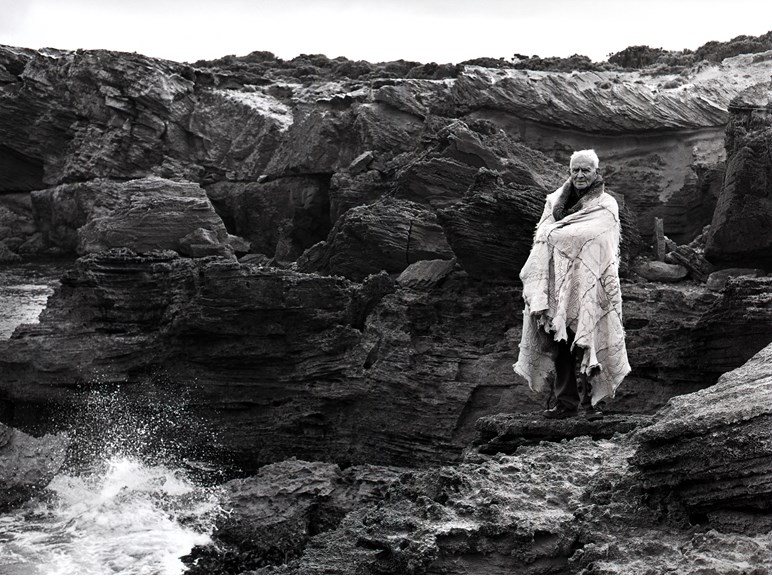

Vicki Couzens is a master cloak maker

Her great-grandfather was one of six men who made the historic Lake Condah cloak.

When she looks at its designs she is drawn to the red ochre markings, still vivid more than 145 years after it was made. Most alluring to her eye too, a symbol of the lake itself.

So Vicki depicted Lake Condah in the new cloak as well. Also Gariwerd—or the Grampians—the northern border of her people’s Country. The Gunditjmara Keerray Woorroong Elder says this is key to understanding possum cloak iconography.

'It [the cloak] maps out where those things are: places, totems, food.'Vicki Couzens

Budj Bim is the creator of Gunditjmara Country

Sixty kilometres north-west of Warrnambool, about 30,000 years ago—in an eruption witnessed by Gunditjmara people and recorded in oral tradition—Budj Bim sculpted the land stretching from volcano to Southern Ocean.

Upon rocky lava flow Gunditjmara built stone villages and a network of weirs, channels and traps, now recognised as among the oldest and largest aquaculture systems on Earth.

On Saturday, 6 July 2019, Budj Bim officially joined the Sydney Opera House and Great Barrier Reef on the UNESCO World Heritage list. In doing so, it became the 20th such site in Australia, second in Victoria and first in the country listed solely for its Aboriginal cultural importance.

Today Gunditjmara rangers like Braydon Saunders manage parts of that Country again, reclaiming land his Ancestors never ceded. Ancestors who made the Lake Condah historic cloak.

Saunders says the etchings on the Condah cloak can be likened to a topographic map.

'There are different spots within the landscape that do pop out when you see the cloak designs,' he says.

'In particular, the lava flow that we have here on Budj Bim landscape'.

'There’s different circular designs in it as well that remind me of the stone hut sites and villages.'Braydon Saunders

Eileen Maude Alberts feels a rap on her knuckles from an invisible hand

It happens, sometimes, when she misses a stitch on an eel trap—or basket.

The traps are long, fibrous tubes with a rim and opening at one end which tapers off like a wizard’s hat.

It was for Anguilla australis, the short-finned eel, that Gunditjmara built their weirs and channels. With these they trapped and fattened eels, caught and smoked them in hollow gums. The eels were staple protein, valuable trading commodity, the foundation of a way of life. So making eel baskets is fundamental to Gunditjmara culture.

'It’s a skill that we would have lost, if it wasn’t for one woman.'Aunty Maude

'Her mother was raised on the mission, so she was raised with that mission mentality about not doing anything cultural, not practicing her cultural beliefs, and refused to show her daughter how to make the eel baskets.'

Undeterred, the girl spied on the Gunditjmara basket makers, saw where the women gathered reeds and how they stitched baskets.

Over time, the girl became the sole receptacle of that knowledge. Then she grew old and died. But not before passing on her knowledge to Aunty Maude and others of her generation. Now they pass it on to their daughters.

So while, Aunty Maude feels the little slap of her mentor when she errs, that Elder must be looking on with pride.

'It’s something that's not going to disappear now,' Aunty Maude says.

Aunty Maude is proud. So when the cloak came to her, for her stories, this was what she chose to tell.

'Those sort of feelings that I have are on this cloak.'

The fibres of possum fur are hollow

It means their pelts provide better insulation than kangaroo, better protection against the rain that falls and Antarctic winds that blow on Gunditjmara Country.

But being smaller marsupials, many pelts are needed to craft an adult-sized possum skin cloak. Fifty pelts were stitched together for the historic Gunditjmara cloak.

The new cloak is not only a patchwork of pelts, but of stories too. Twenty-six adults and 11 children created the new designs. With wire-nib burners they told stories of cultural practice. Stories of Country and of place, of brolgas reclaiming habitat, of cockatoos and kangaroos. Stories of individuals—one man’s designs spoke of his travels between western district towns for work, to visit his daughters.

When she’s asked how the cloak feels to touch, Aunty Titta says its warm.

' But also, it’s strong, it holds everybody in,' the Elder and cloak maker says.

'Your feelings, your emotions. Past and future, all wrapped in one.

'That’s the only way I can put it.'

Historic cloaks are bridges into the past

But while the historic Lake Condah cloak is a source of pride for Gunditjmara people today, it is also something of an enigma, Aunty Maude says.

'We don’t know how old it really is because we don’t know how old it was when it was handed to the museum,' she says.

'We can have a really educated guess about what the drawings are on the old cloak but, on this [new] cloak, we know what the drawings represent and that’s important because it's that continuing connection to Country.'

In 150-years' time the descendants of today’s Gunditjmara cloak makers will know about their Ancestors' day-to-day lives, their struggles and triumphs, their land and beliefs.

'It’s ... keeping all those things very much alive.'

Written by Joe Hinchliffe, Museums Victoria