Pressed Orchids

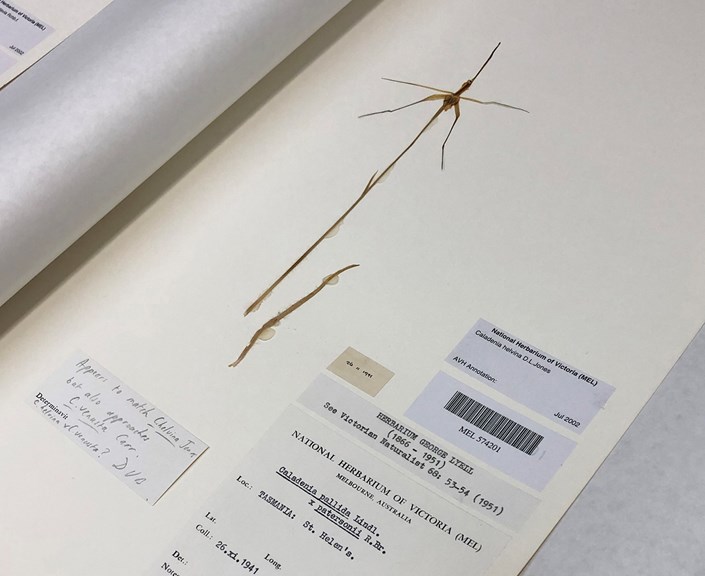

Unlike their Asian counterparts, Australian orchids like the rosy spider orchid, pictured below, are beautifully understated. Delicate and beautiful, they are not flashy like the orchids available at your local nursery.

The rosy spider orchid is endemic to Tasmania, and it is now part of the pressed orchid collection at the National Herbarium of Victoria. George Lyell, to whom it belonged, never visited Tasmania, as far as we know. He visited southern Queensland and South Australia, once each, and made a couple of trips around Sydney. But for the most part he collected locally, around Gisborne, his adopted hometown in rural Victoria, the source for many of his moths, butterflies, and orchids.

We're not sure who sent this specimen from Tasmania but we do know that a Miss A. M. Tagg sent Lyell some rare hepialids in 1941. The Tagg family owned the well-known tourist attraction, The Homestead Tea Gardens at Ridgeway, 7 kilometres from Hobart. Famous for their beautiful gardens, Miss Alice (Mem) Tagg also ran the local post office, so sending specimens interstate was no problem. St Helen’s is a long way from Hobart, so possibly someone had sent it to her, knowing that she was interested in all aspects of the natural world.

Was George Lyell attracted to spider orchids because of their insect-like appearance? No doubt. But there is an even more intimate connection between insects and orchids, as Edith Coleman, his contemporary and fellow member of the Victorian Field Naturalists' Club, confirmed in the late 1920s. For a long time there had been puzzlement (and some suspicions!) over the relationship between wasps and orchids, but it was Coleman who confirmed that male wasps pollinated orchids by copulating with them.

Naturalists had for a long time wondered why male wasps embraced the orchid's labellum (little lip) so enthusiastically, despite the fact that the orchid offered the insect no nectar or edible material. Coleman had no doubts about what was going on, especially as the male wasp darted backwards instead of head first into the flower's stigma, its body taking 'an inward falcate curve' where it 'quivered for a moment, and then became motionless' (Victorian Naturalist, vol. 44, May 1927, p.20). Minute observations like this over many days convinced Coleman and her daughter Dorothy that the orchids lured male wasps to copulate with them, using their lusciously deceptive smell. This phenomenon is known as pseudocopulation.

Some orchids, such as the hammer orchid, even added a very close physical resemblance to the female wasp, mimicking its precise dimensions and shape. Lyell was a subscriber and contributor to The Victorian Naturalist and he almost certainly read Coleman’s remarkable account of her observations. We now know that the orchids’ delicious ‘perfume’ is composed of the mimicked pheromones of female wasps. For more on Edith Coleman, see Danielle Clode’s The Wasp and the Orchid (Picador, 2018).

Lyell moved to Gisborne in 1890 when he was 24 years old, after being offered a job at the timber merchants firm, Cherry & Sons. He liked to go on long walks in pursuit of insect and orchid specimens, sometimes at a distance from Gisborne, where he lived until his death in 1951. When he had to have surgery to remove his prostate gland in 1932, he decided it was time to begin arranging for his moth and butterfly collection to be donated to the National Museum of Victoria. Fortunately the surgery went well and six months later he could boast in a letter to Daniel Mahony, Director of the National Museum: "My health seems to be almost normal now – I had a three mile walk in the snow storm on Sunday afternoon and feel none the worse for it" (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579).

The delicacy of many of Australia's orchids makes them hard to spot in the bush, akin to the challenge of spotting moths and butterflies. Lyell no doubt enjoyed the challenge of finding these beautiful plants, and he prepared them for preservation and documentation as meticulously as he prepared his insect specimens.

In the Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Lyell, the entomologist Arturs Neboiss noted that he had an orchid collection but it was Nik McGrath, Museums Victoria archivist and a Chief Investigator on the McCoy Seed Fund Project, 'George Lyell Collection: Australian entomology past and present', who made the exciting discovery that Lyell had donated this orchid collection to the National Herbarium of Victoria [ARCHIVE-BOX~579; 23 July 1932 to 15 January 1952].

Simon Hinkley, Entomologist on the project, immediately contacted the Herbarium, and just as he was unaware of Lyell's orchids across town, the Herbarium's collection managers were unaware of Lyell's insects up north at the Melbourne Museum. One of the tasks of this project will be to update biographical information in the Collection Management Systems of both institutions so that this link between Lyell's two collections is not lost to future researchers.

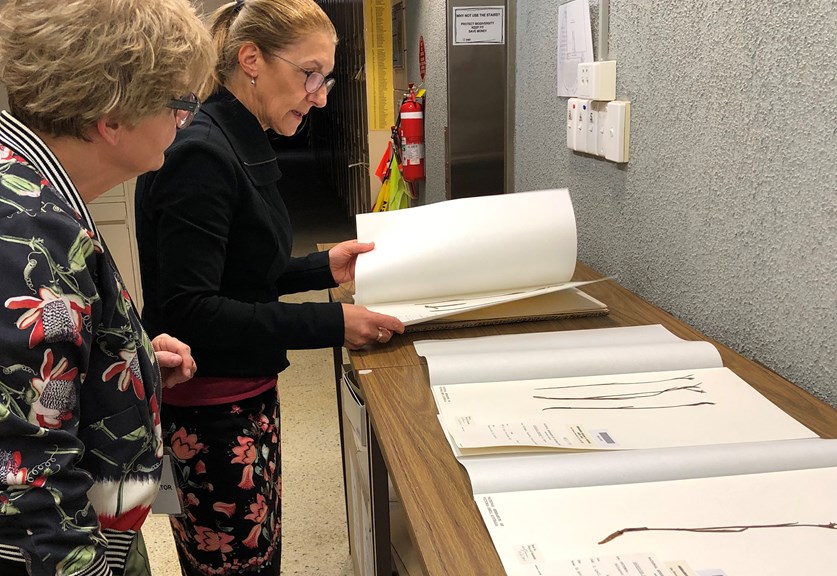

Moss expert Pina Milne, Manager of Collections and a passionate advocate for access to them, has worked at the Herbarium for 20 years. She arranged for Professor Deirdre Coleman and Nik McGrath to access samples of Lyell's orchid collection. She also took the time to acquaint us with many wonderful digital sites: the Australasian Virtual Herbarium, Atlas of Living Australia, JSTOR Plants (Global Plants), VicFlora (Flora of Victoria), and HortFlora (Horticultural Flora of South-eastern Australia). For digitised publications there is also the Biodiversity Heritage Library, but we knew about that one!

For an insight into the work Pina, her staff and volunteers do, see the short documentary on YouTube called Hidden Secrets of the Herbarium (2014). Here you can see the detailed work that is needed to press, dry, mount and label specimens, add their information to the database, then send the data to the Australasian Virtual Herbarium. Finally the specimens are digitised and added to the Global Plants Initiative. "We continue to add stories to the records we have and every individual sheet has something to tell us", Pina notes at the end of the documentary. Lyell's story will now be shared too, hopefully reaching audiences far and wide.

Lyell collected the majority of his orchids in Victoria, but he also collected orchids from Western Australia, Queensland, New South Wales and Tasmania. For a map pinpointing his collection localities, see the Australasian Virtual Herbarium website; and to view the records of these specimens, visit the following page. His collection of over 200 specimens is arranged throughout the family Orchidaceae, by genus and species. Like Lyell’s moths and butterflies, his orchids are not stored together in a separate cabinet but arranged by species amongst specimens collected and donated by many different sources.

After George Lyell passed away on 19 May 1951 in Gisborne, the executors of his estate sent a letter to the Trustees of the National Museum (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579; 28 May 1951) regarding his will and the two destinations of his collections: the National Museum of Victoria and the National Herbarium of Victoria.

Mr Hitchcock, the Museum’s ornithologist, and Mr Hobbs from the Union Trustee Company of Australia Limited were sent to Gisborne to compile an inventory and draw up a valuation of the collections. The inventory (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579) listed Lyell's library, index books, specimens (Lyell's moth and butterfly collection had already been transferred to the Museum), entomological collecting equipment and the following:

Orchids

Three large boxes containing pressed specimens of native orchids.

One smaller box of same.

Some loose material.

Three lead weights used for pressing.

Richard (RTM) Pescott, the Museum's Director, sent a letter to the Chief Trust Officer on 27 June 1951 providing an evaluation of the library and entomological equipment, but did not include an evaluation of the orchid collection: "This figure does not include any valuation of the collection of orchids, which could only be carried out by the officer of the National Herbarium at the Botanic Gardens" (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579). Pescott later received a letter from the Trust Officer (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579; 22 August 1951) advising that Mr Jessep, Director and Government Botanist at the National Herbarium, would evaluate the five boxes of Australian orchids. (Museums Victoria Archives, ARCHIVE-BOX~579).

It is interesting to note that Richard Pescott was a botanist and nephew of an eminent orchid authority, Edward E. Pescott. Edward Pescott’s Orchids of Victoria was published in 1928 after appearing in numerous Parts in the Victorian Naturalist. In fact, Part 9, an article of 11 pages, appeared immediately before Edith Coleman’s daring observations on pseudocopulation.

The National Herbarium of Victoria has an interesting history. Its origins in 1853 can be seen in the correspondence between the Government Botanist Ferdinand von Mueller and Frederick McCoy, the National Museum of Victoria's first Director, as Nik McGrath has outlined in Our first Director's vision for a University Botanical Garden.

The Herbarium's original building was on the site of the Shrine of Remembrance but it was demolished to make way for the Shrine in 1934. The front of the present building is Art Deco in design, and a 1989 extension at the back houses the collection. The Victorian Government will give $5 million in funding to redevelop the Herbarium, beginning with a feasibility study in early 2020 (see Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change media release, January 2019).

Written by Nik McGrath, Archivist, Museums Victoria, and Prof Deirdre Coleman, University of Melbourne and lead on the McCoy Seed Funding Project 'George Lyell Collection: Australian entomology past and present'

For previous blogs about the collector George Lyell, see our previous articles Butterflies of the night and Like moths to a flame.

If you have any questions or feedback about the project, please contact Nik McGrath at [email protected].

This article originally appeared as a University of Melbourne blog post.