Paying tribute to one of our hardest-working specimens

At Melbourne Museum, in the Science and Life gallery, right at the end of the Dinosaur Walk exhibit, stands a skeleton cast of the creature now known as Diprotodon optatum.

BY NIK MCGRATH AND BELINDA BORG, MUSEUMS VICTORIA ARCHIVES

This skeleton has been entertaining visitors since the Museum first opened in October 2000, but items from the Museums Victoria Archives can shed some light on the hidden story behind this beloved specimen.

This diprotodon has been part of the museum Collection since 1906, and for nearly all of that time it has been on display.

There is a wealth of information to be found in the Archives regarding the acquisition of many items in the Collection, and this Diprotodon specimen is no exception. Using the Reports of the Trustees of the Public Library, Museums, and National Gallery of Victoria we learn that the cast was made by staff of the South Australian Museum, in Adelaide, from bones discovered at Lake Callabonna, South Australia, in 1893. This discovery was the first time a complete skeleton of diprotodon had been unearthed, before then, palaeontologists only had available to them pieces of jaws, teeth and limb bones, and these were often damaged or incomplete.

Newspaper reports indicate that for the staff of the South Australian Museum, collecting the bones, reconstructing the skeleton and then creating a cast proved to be quite a process, taking them almost 13 years and costing an estimated £1000 to complete. The museum persevered however, and planned to recoup these costs by selling replicas of the cast to other museums and similar institutions around the world.

Our National Museum and the Cambridge Museum, United Kingdom, were the first two institutions to purchase these replicas. Our purchased cast was first displayed in the National Museum in May, 1907. From the Archives, entries in an Accounts Ledger shows that the cost of the cast was £50, plus packing and shipping expenses. To put this cost into perspective, the minimum wage was first introduced in Victoria that same year, in 1907, and amounted to £2/2 a week.

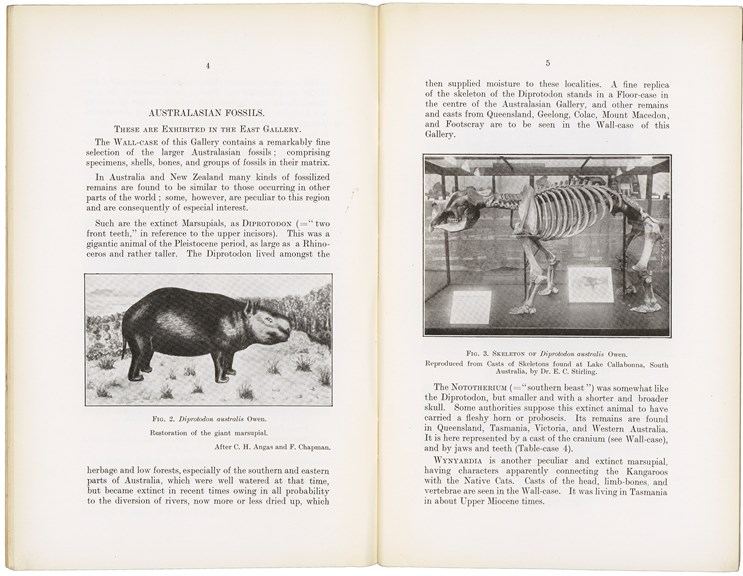

In the Museums Victoria Archives there is a photograph of the diprotodon, taken in December 1928, when the skeleton cast was displayed in the centre of the Australasian Fossil Gallery at the National Museum, which was then located where the State Library of Victoria is now, in Russell Street, Melbourne. This photograph was most likely commissioned for use in the Illustrated Guide to the Collection of Fossils exhibited in the National Museum, by Frederick Chapman, Palaeontologist of the Museum, which was published the following year, in 1929.

There is another photograph of the Diprotodon, still on display at the National Museum, in the University of Melbourne’s photograph collection, which we believe was taken around 1950.

Age has proven no barrier to diprotodon’s charm over the years, as a new photograph of the specimen graces page 17 of the recently published children’s book, From Dinosaurs to Diprotodons – Australia’s Amazing Fossils. Written by Dr Danielle Clode, and published by Museums Victoria, this book is filled with interesting facts and images about Australia’s extinct megafauna.

Despite the relatively significant cost of purchase at the time, it’s safe to say that the diprotodon has definitely earned its place as a treasured specimen here at Museums Victoria, entertaining visitors for over 111 years (and counting)!

Restorations / Illustrations

Before the Lake Callabonna discovery in 1893, palaeontologists had only ever found pieces of Diprotodon fossils, such as bone fragments, teeth or sometimes part of a jaw or skull. Even though they only had fragments to work with at the time, scientists still attempted to illustrate what these unknown creatures might have looked like.

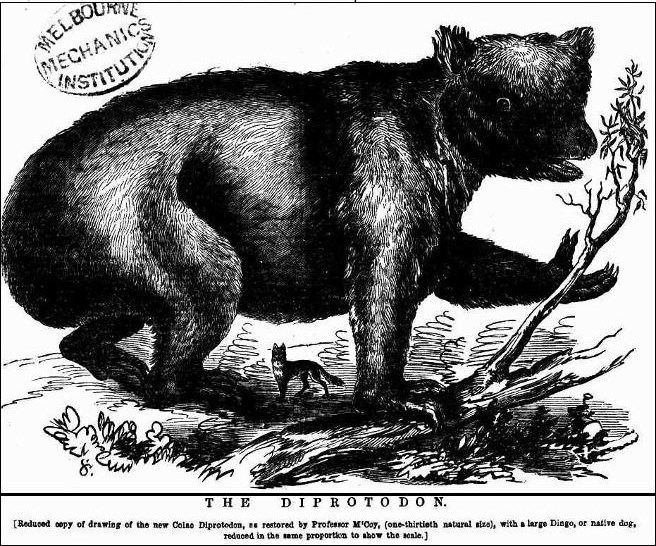

One of the earliest renderings of a Diprotodon that we were able to find was actually created by the first Director of the National Museum, Frederick McCoy, who held that position from 1856 till his death in 1899. McCoy’s assumptions, made in 1862, of what the Diprotodon looked like are based solely on teeth, jaw and arm bones fragments available to him at the time. McCoy created this illustration to go with a paper he presented on 30 September 1861 at the Royal Society of Victoria's monthly meeting, titled "On the bones of a gigantic marsupial, found near Colac, with observations on the genera Diprotodon and Nototherium."

A life-size wooden version of the Diprotodon, based on McCoy’s restoration, was erected in the gardens at Melbourne Zoo around August 1888, and stayed there until at least 1906 (which incidentally was when the completed Lake Callabonna skeleton was revealed to the world).

To coincide with the completed assembly of the Lake Callabonna skeleton, C H Angas created a new restoration of the Diprotodon for the South Australian Museum in 1906, which is markedly different from McCoy’s earlier version. A modified version of Angas’s restoration, made by Frederick Chapman, was used in the Illustrated Guide to the Collection of Fossils exhibited in the National Museum in 1928.

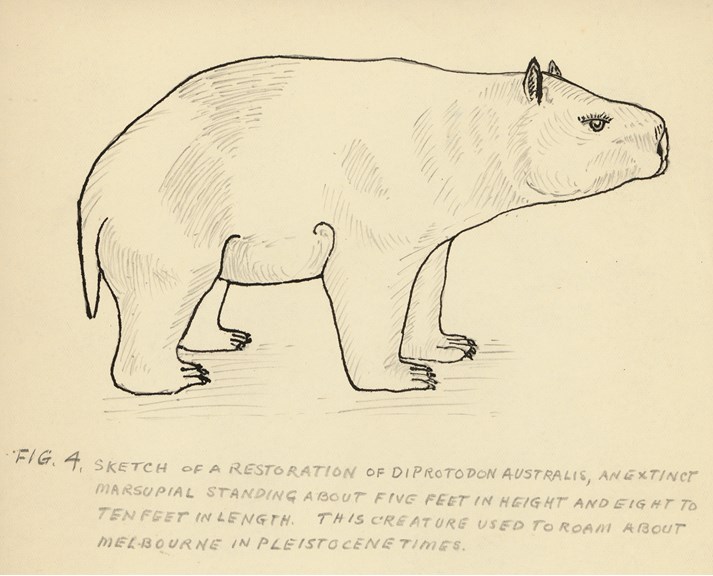

The Museums Victoria Archives also holds a sketch of a Diprotodon made around the 1940s-50s by a geologist, George Baxter Pritchard. It seems this illustration was to be included in a manuscript, tentatively titled "Old Port Phillip History as Told by Geology", which sadly was not completed by the time of Pritchard’s death in 1956. However, this illustration is a useful indicator of the changing opinions of scientists regarding the physiology of Diprotodon over time.

The most current restoration of Diprotodon was created by artist Peter Trusler in October 2008, and was used in a series of stamps released by Australia Post that same year. A modified version of this illustration can be found on the front cover of From Dinosaurs to Diprotodons – Australia’s Amazing Fossils.

Early Specimens (diprotodon collecting in the 19th Century)

Evidence from the Museums Victoria Archives and newspaper articles from around 1860-1899 indicate that the first Director of the National Museum, Professor Frederick McCoy, had a keen interest in the diprotodon. McCoy, who was also a member of the Royal Society of Victoria, wrote and read a paper at the Society's monthly meeting in September 1861, titled, "On the bones of a gigantic marsupial, found near Colac, with observations on the genera Diprotodon and Nototherium."

Not long after the presentation of the paper to the Royal Society, there was a unique exchange of letters between McCoy and Mr Rob. Wood Wilkinson, a chemist from Back Creek, near Talbot in Victoria. The correspondence was initiated by McCoy, who, upon attending the Victorian Exhibition, held in October 1861, noticed the specimens exhibited by Wilkinson and, believing them to be diprotodon fossils, wrote to see if Wilkinson would be interested in donating them to the National Museum collection. Unfortunately for McCoy, Wilkinson had long ago determined that his specimens were to end up in the Kew Museum in London, United Kingdom. Even McCoy’s offer of sending some duplicate specimens from the National Museum to the Kew Museum, in exchange for the diprotodon specimens remaining at the National Museum, was not enough to dissuade the steadfast Wilkinson.

Correspondence from 1870 between McCoy and John Coleman, of Colac, shows that McCoy was so desirous of diprotodon specimens that he was willing to pay for them. In a letter from the Archives dated 25 June 1870, Coleman informed McCoy that he had received a box of "bones and parts" of the Diprotodon, and that the "finder", who was "making a water hole" when they made the discovery, required £10 in payment. McCoy readily agreed to these demands, however a further letter sent from McCoy to Coleman over a year later, on 14 August 1871, stated that he "greatly regrets the delay in providing the money for the Diprotodon bones which arises from the difficulties of new Trustees interfering with the management of the Museum…" From early 1870, the newly formed Trustees of the Public Library, Museums, and National Gallery of Victoria had taken control of the administration and finances of the National Museum, and McCoy clearly resented what he termed their 'interference' into these and similar financial matters.

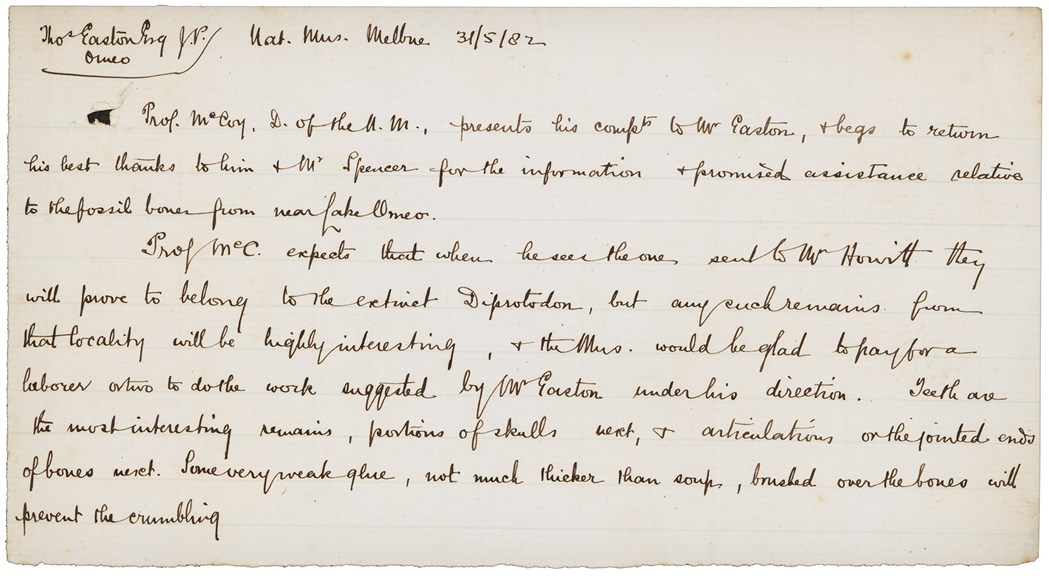

However, McCoy’s interest in diprotodon continued to grow over the years, as can be gleaned from an exchange that commenced in May 1882 between McCoy and Mr Thomas Easton, the Secretary of the Shire of Omeo, in Victoria. Easton had sent a bone fragment found by workers while sinking a well near Lake Omeo, and advised that there were other, much larger bones at the same site, but they were so fragile that they broke when the workers tried to extract them.

McCoy quickly replied to Easton, and proposed that "…the Museum would be glad to pay for a labourer or two to do the work suggested…" McCoy’s letter also included some advice on how to protect the fossils, "Some very weak glue, not much thicker than soup, brushed over the bones will prevent crumbling"; as well as directions on where the workers should focus their energies, "[t]eeth are the most interesting remains, portions of skulls next, and articulations or the jointed ends of bones next".

At this point no complete skeleton of Diprotodon had been found, and just imagine how excited McCoy must have been at this prospect. Immediately following this letter however, there is a break of almost a year until Easton writes on 30 April 1883, mentioning that he has been delayed due to agricultural works conducted by the property owner on the site. However, the work is now clearly in swing, as Easton includes an invoice entitled "Amount expended for search of bones of Diprotodon", with payment to be made to two labourers, William Hardy and G W Miller, who both signed the invoice.

On 5 May 1883, Easton informs McCoy that he will "…forward by next post a packet containing some teeth and tusks found in the excavation on Mr Spencer’s land near Lake Omeo". Unfortunately, it seems the packet does not contain the diprotodon fossils that McCoy was seeking, his disappointment evident in the reply dated 16 May 1883, "The bones received by post are only those of a fossil Kangaroo, and it would perhaps be scarcely worth continuing the excavations much further."

These pieces of early correspondence from the Museums Victoria Archives can help us better understand the collecting practices and interests of Professor Frederick McCoy, the first Director of the National Museum. McCoy was clearly enamoured with the diprotodon, and it is a shame that the first complete skeleton of a diprotodon would not be revealed to the public until 1906, 7 years after McCoy’s death in 1899.