Moths are beautiful too

Nocturnal is a night when Melbourne Museum opens its doors after hours for visitors 18 years and older to enjoy live music, drinks and chats with Museum staff who bring out items from the collection for a special ‘show and tell’.

Leading up to the night I thought my main objective would be to present moths in a way that might change preconceived negative views of visitors. I also hoped to share some stories from letters in the Museums Victoria Archives that may surprise and touch the feelings of visitors. I wanted to break down stereotypes about archives. Some may view archives as dull, but in fact archives are full of intrigue and rich content not only of interest to researchers, but to individuals from all walks of life.

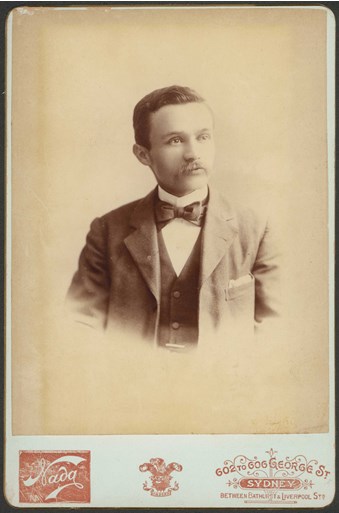

The George Lyell Collection at Melbourne Museum includes his Lepidoptera Collection which totals 51,216 specimens representing 6,177 species, and containing some 534 types; almost 12,000 butterflies and 40,000 moths. Lyell’s correspondence, notebooks and draft manuscript of The Butterflies of Australia are held in the Archives. The published annotated Butterflies of Australia (1914) is in the Rare Book Collection.

On 4 October 2019, a multidisciplinary team of Museum workers, Nik McGrath (Archivist), Simon Hinkley (Collection Manager in Entomology and Public Information Officer), Hayley Webster (Library Manager), and Mark Nikolic (Legacy Registration Officer, Sciences), and a guest speaker from University of Melbourne, Professor Deirdre Coleman (School of Culture and Communication) teamed up to present items from the George Lyell Collection to Nocturnal audiences. About 800 tickets were sold before the night. I haven’t seen the full numbers but it felt like there were over 1000 engaged visitors in our location of SciPod (near Dinosaur Walk and Bugs Alive!) asking some really interesting questions. These were not exclusively on the collections we had brought out for display, but on a variety of subjects.

I managed to capture the above moment when my friend Richard Morden was showing Simon Hinkley an image on his phone of a spider with its guts hanging out, on the point of asking a question. I have a feeling Richard was asking Simon to ID the spider. After I captured this moment visitors arrived at my table so I went over to talk to them and missed the rest of this exchange. Nocturnal is not only about discussing what is on the table, but about other aspects of museum work, and what it’s like to work in a museum. I had some fascinating conversations with visitors about human remains in the collections. One visitor mentioned that they had seen human remains on display in a museum overseas and this kicked off a discussion around repatriation of human remains, and the important work current museum staff do in this area with Indigenous communities.

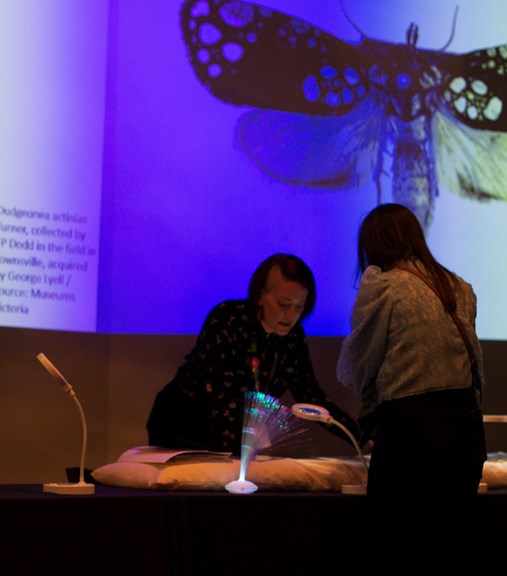

In the image above Ruth captured a moment when I was talking to a visitor about a letter in the Museums Victoria Archives that I discovered when transcribing the letters of GA Waterhouse to George Lyell. I said to the visitor: ‘Do you want to hear a sad story?’ The visitor was from Ireland, and had a particularly strong accent. She replied, perhaps a little warily, that she did want to hear the story. I went on to say, ‘this piece of paper might not look like much.’ I then held up a piece of paper protected in its Mylar sleeve to show the visitor. ‘This is a letter GA Waterhouse wrote to his friend and colleague George Lyell on 12 July 1943. They corresponded between 1891 and 1947. Can you see the writing looks almost childlike?’ The visitor replied ‘yes’.

I then went on to say I’ll read the letter to you: “You will be disappointed to learn that three weeks ago I had a slight stroke. I have been out of bed for 3 days now in a wheel chair. I am writing this with my left hand sitting in the sun on our balcony. I am hoping to get the use of my right hand soon. So far I can move everything more or less normally on the right arm down to the wrist. The right leg is almost normal. Today I walked a few steps with the nurse […] I think I have made a good start with writing with my left hand. It is barely 14 days since I made the first attempt [...]” (OS~03031 Museums Victoria Archives).

I explained to the visitor that being in a wheel chair and being unable to go out into the field to collect or to observe butterflies and moths, something both Waterhouse and Lyell lived for, would have been absolute agony for both. Since they were such close friends, knowing that the other was suffering was probably too much to bear. Lyell and Waterhouse had been friends for 52 years when this letter was sent. They spent most Easters together. Lyell, who lived in Gisborne, would travel to Sydney to stay with Waterhouse and his family. They were close friends and colleagues, not only sharing a passion for moths and butterflies, but sharing that time with their families and friends. I went on to tell the visitor that Waterhouse passed away in 1950 and Lyell in 1951, although Waterhouse was 11 years Lyell junior. I feel, in a romantic way, not at all based on science, that their close personal bond meant that they couldn’t go on long without each other.

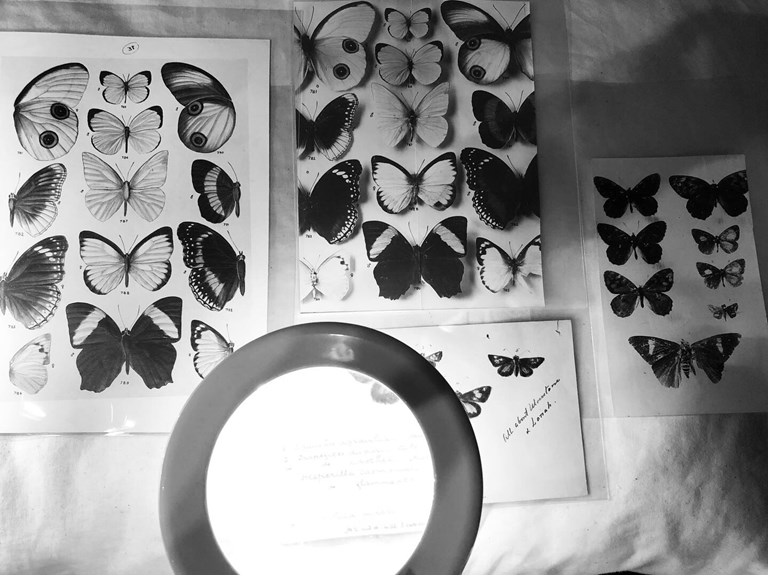

Another thing I enjoyed pointing out to visitors during the evening were the proofs of Butterflies of Australia (1914) held in the Museums Victoria Archives. In the photograph above in the middle top is a photograph of butterflies taken by Mr Henry King, Sydney which was used as a reference for the illustration on the top left. I would say to visitors ‘Can you tell these two apart? Which is the photograph and which is the illustration? How fine is the work of the illustrator?’ Each visitor nodded in agreement. I went on to explain that the illustrations were by Mr AR McCulloch, colour plates painted by Mr HW Simmonds; and drawings of larvae and pupae by Miss J Kong Sing. I also explained that standing next to me was Hayley Webster who was exhibiting the annotated author’s copy of Butterflies of Australia (1914) from the Library’s Rare Book Collection. The final illustrations in this volume can be compared to the proofs held in the Archives. The annotated copy belonged to George Lyell, with pieces of writing paper interleaved in the volume and bound, so that Lyell could write notes and corrections in the years following the book’s publication. Lyell and Waterhouse corresponded about corrections they had identified, such as an incorrectly identified gender or the discovery of a certain species at another locality.

Another story from the night surrounded the drawings of larvae and pupae by the mysterious Miss J Kong Sing from Sydney. I had some very excited conversations about the importance of telling the stories of women in the Archives, especially as stories about men dominate the historical record. I noted the skill of Miss J Kong Sing (an illustration with her signature is available for viewing on the Biodiversity Heritage Library). I told visitors ‘I don’t even know her first name’ and explained how I needed to do some more research on Miss Kong Sing. Following Nocturnal, I went down the Trove rabbit hole, and found several references to Miss J Kong Sing in newspapers. Miss Kong Sing specialised in miniatures, and had studied at the National Gallery of Victoria before moving to Sydney where she exhibited her work at the annual Royal Society of Art exhibition, reported in the newspapers in 1903 and 1905. Not long after her illustrative work for the Butterflies of Australia in 1914, Miss Kong Sing moved to Europe where she spent 10 years in Spain and about 10 years in London. In London she studied at the Westminster School of Art. Miss Kong Sing made many notable miniature portraits of London personalities. On the outbreak of war in 1939, she returned to Sydney. This is all I’ve discovered so far, but my next step will be to find a photograph of Miss Kong Sing and discover her first name.

Thank you to all of the visitors to Nocturnal. I asked a number of visitors why they were there, and I was pleasantly surprised that many of them had come to see ‘museum things’ first, and live music second. Many visitors expressed excitement about being in the Museum at night, and seeing the exhibits, especially the dinosaurs, lit up so dramatically. One visitor told me it was her fourth Nocturnal, and she was addicted! Hope to see you at a future Nocturnal, and if you see me, please do come and have a chat. I’ll leave you with one final anecdote. I asked visitors if they were scared of moths. Some answered ‘yes’. I then asked them to come up close to one of Lyell’s specimen drawers to see a moth up close and to see the beauty of the markings on their wings. It was amazing to see how surprised people were to see the beauty and variety of moths. Hopefully some visitors walked away with a new appreciation for moths. Some of Lyell’s incredible collection can be viewed on Museums Victoria’s Collection website. What do you think, are moths beautiful?

The George Lyell Collection: Australian Entomology Past and Present McCoy Seed Funding Project is led by Professor Deirdre Coleman, School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. Nik McGrath, Archivist, Museums Victoria, is the coordinator at Museums Victoria, with colleague Simon Hinkley, Collection Manager, Entomology and Arachnology.

Written by Nik McGrath, archivist, Museums Victoria.

Written by Nik McGrath, Archivist, Museums Victoria

If you’re interested in learning more about the project, see our previous articles Butterflies of the night, Like moths to a flame, Pressed Orchids, The sting of the final letter, Light sheets and Kindred spirits.