If books could kill: poison, heavy metal and literature

Poisonous books are a legacy of fashion and industrial practices that prioritised beauty above all else. And the heavy metals left behind are still causing headaches for libraries and museums to this day.

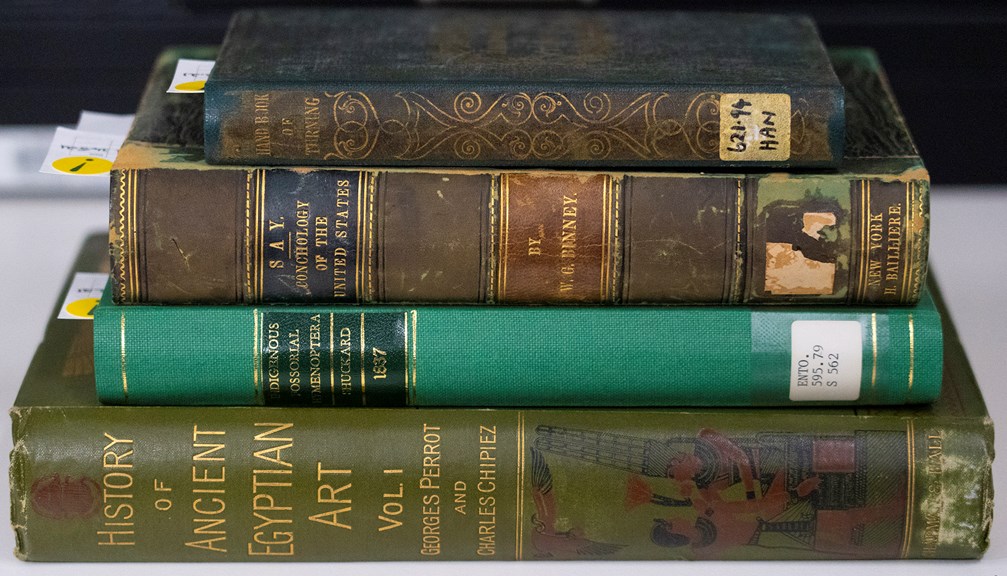

Books are not usually thought of as hazardous objects, but you will want to be careful with these ones from the Melbourne Museum’s Rare Book Collection.

Poisonous heavy metals permeate their very fabric, and the last 150-odd years has done nothing to lessen their toxicity.

How did it happen though?

This is not some dastardly Name of the Rose-esque plot but rather a combination of fashion, vanity, and workers’ rights (or lack thereof) in the years following the Industrial Revolution.

And it has left a dangerous legacy for modern-day museums.

The eyes of the beholder

The 1800s were a time of extravagance in western cultures—featuring flamboyant feathered hats and vibrantly dyed clothing.

The Industrial Revolution of the preceding decades brought luxury goods to the masses and consumers were looking to make themselves stand out from the ever-growing crowd.

‘And books were certainly fashionable items,’ says Hayley Webster, the manager of Museums Victoria’s library.

Private collectors used to have their books bound in leather to match their own libraries.

‘As publisher bindings were introduced, the cost of paying for the bindings went from the owner to the publisher,’ says Hayley.

Cloth bindings were introduced as a cheaper alternative to leather in the 1820s, but publishers were continually experimenting with covers to make them appealing to prospective buyers.

‘As they developed greater techniques, the bindings became much more elaborate,’ says Hayley.

And in the middle of the century publishers started using highly desirable, and vibrant, pigments like Emerald Green.

Unfortunately, a key ingredient was arsenic—a highly toxic heavy metal that can cause skin lesions and cancer, among other ailments.

‘It became really fashionable, which is why people got sick,’ says Museums Victoria materials scientist Rosemary Goodall, who identifies hazards in the museum’s collection.

The popularity of these arsenic-based pigments meant they were used in everything from dresses to wallpaper.

‘The books that are bound in the green poisonous cloth, there needs to be some abrasion, or it has to be wet for the hazardous substance to actually pose a threat,’ explains Hayley.

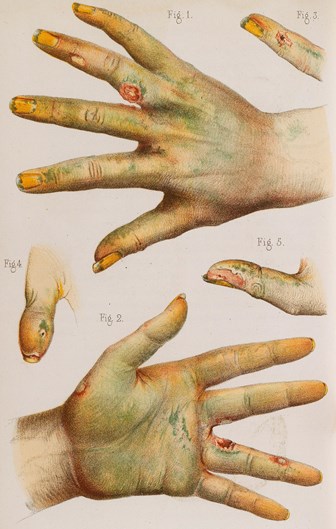

It is for this reason that museum staff take precautions, including wearing gloves, but the people making these dyed fabrics didn’t have that choice.

‘It was a cavalier attitude to the use of these toxic materials,’ says Rosemary.

‘The health of the worker was not considered to be that important in a lot of these situations.

‘There were companies that progressed that and improved safety, but there were no regulations until much later.’

Factory workers often suffered severe injuries to their hands from repeated exposure.

They heyday for arsenic-based pigments occurred between 1850 to 1880, but their decline was not solely due to concerns about its toxic nature.

‘There was definitely an awareness that it is toxic, but the main driver was probably more fashion than the toxicity,’ says Rosemary.

Arsenic-based pigments continued to be produced well into the 1900s, until regulation put an end to their manufacture.

But amongst the litany of Victorian-era artefacts known to harbour this poison, books largely went under the radar.

‘This is fairly new in the area of libraries,’ says Hayley.

‘I'd heard about arsenic in the context of wallpapers and fashion, and I was not aware of its application to books.’

Sparked by the Poison Book Project, Hayley and Rosemary have been investigating the extent of these hazards in the rare book collection at Museums Victoria.

And while bright green covers might be an obvious place to start, arsenic is proving to be the tip of the iceberg.

Red flags of every colour

Of 120 books Rosemary tested, just four in the museum’s collection contained arsenic while 110 had high levels of lead.

Carbonated lead was used as a white pigment base for centuries—famously in makeup favoured by the English aristocracy, including Queen Elizabeth I.

Lead is a neurotoxin that is especially harmful to children, and it builds up with repeated exposures.

‘High concentrations can cause severe headaches, delirium, coma, brain damage, and possible death,’ says Rosemary.

Despite knowledge of its toxicity for thousands of years, lead was widely used in medicine, paints, and even petrol.

‘Lead white as a pigment was really popular…it was the white pigment—if you wanted to adjust the colour of a pigment, you mixed it with lead white or you used lead white as a foundation.’

And it is not just white; lead was used to create other popular pigments too, including red lead and vibrant yellow lead chromate favoured by Vincent van Gogh.

In addition to its use as a pigment in book binding, says Rosemary, ‘The reason it can be present everywhere is that it was also used as a drying agent.’

‘So it's not surprising that I find lead everywhere.

‘The amount of lead that I find in book covers is continuous right through until the 20th century.’

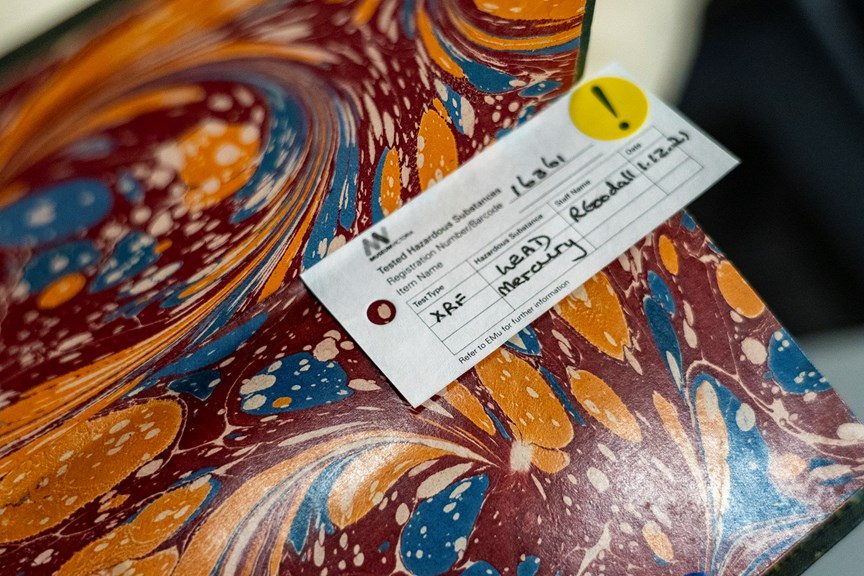

But lead is not the only heavy metal that can be used to create a red pigment.

For thousands of years, those in search of a brilliant red pigment favoured vermilion—a powdered form of the mineral cinnabar, otherwise known as mercury sulphide.

And, as with other heavy metals, mercury’s toxic nature was well known by the 1800s.

‘They were still using mercury on hats, despite the fact that they knew how toxic it was, and it was used in medicine way into the 20th century,’ says Rosemary.

Vermilion was widely used in watercolour pigments employed before the invention of colour printing.

While these pigments give off mercury vapour, Rosemary says, ‘The amount would be so small from a watercolour illustration that it's probably not going to be hazardous to staff handling it, or people reading the book.’

In the museum’s collection though, it can also be found in the marbled paper on the inside covers of some books.

‘It's obvious that vermilion has been used in creation of those colours,’ says Rosemary.

‘We're finding some other heavy metals on there as well, which is good news because that makes us aware of what other hazards are on these covers.’

And that brings us back to the point of these tests—to understand what hazards have gone unnoticed for so many years in these collections.

‘Books traditionally are seen as fairly safe objects,’ says Hayley, ‘Now I'm feeling like there's a lot more to learn and a lot more that I need to know.’

‘This sort of process and this project is really important because that's going to at least provide me with the general knowledge to make decisions.’

And the information gained through this testing doesn’t just benefit Museums Victoria.

‘We've got such fantastic expertise in our conservation team and in our institution but for smaller organisations, that kind of expertise or the ability to test isn't always there,’ says Hayley.

‘Getting the information out there is really important.’

Are my books ok?

According to Museums Victoria’s experts, while there are sometimes hazardous substances in old books to be aware of, generally people are at no immediate risk of harm when handling old books.

In most cases, any toxic substances are bound up within the materials of the book and will not readily lead to exposure unless the surface is abraded or wet.

This risk is more present for those who do regular, interventive work with old books, such as conservators, rather than those who have casual contact.

AICCM, the professional organisation for conservators in Australia, provides a database of specialist conservators who can provide technical analysis:

AICCM | Find a Conservator.

Got a question? Ask Us about it.