A discovery of stitches: needlework and 19th century girlhood

What can needlework samplers tell us about often forgotten figures from history?

I first met Eliza Winter a few years ago.

She’s not the sort of person I’m usually drawn to—for starters, she’s a lot younger than me and our lives are very different.

Eliza’s fine needlework is what first caught my eye, in fabric sewing samplers she made at five and a half years old.

I sew a little myself but my skill with a needle doesn’t come close to Eliza’s, even at this tender age.

Looking at her work I can see Eliza’s small fingers holding the fabric, little balls of thread around her, needle poised to start her work.

Her stitches are very small and delicate, and the thread remarkably colourful.

Two later samplers show how her skill and confidence increased over the years and portray a playful, and vibrant personality.

But one of them is unfinished.

At age 11 Eliza fell ill with a fever.

Four days later she passed away.

The thing is, all of this happened 170 years ago.

Stitching the pieces together

The lives of children today can be traced and remembered by a plethora of information and physical items—artwork and craft, photographs, social media posts, messages, clothing and toys.

But it’s not that easy to know what life was like for kids, especially girls, from Eliza’s time.

Official records tell us when they were born and when they died but provide little to no detail about what happened in between.

Objects that girls made, wrote, or used offer a richer picture.

But the reality is that most children in 19th century Melbourne left few things behind to remind us of their existence.

The items that do remain paint a somewhat shadowy picture of girls’ lives—their education, work, family life and leisure.

Eliza’s sampler offers us some clues.

Born in 1842, Eliza was one of nine children.

She didn’t put this level of detail into her sewing but she did embroider her name (E. Winter), her age (not just five, but five and a half), and the year her sampler was made (1847).

With only these scant details, I had to find out more.

Searching through records I discovered that Eliza was born in Sydney and moved to Melbourne as a toddler.

Her family home was at 172 La Trobe Street, right in the heart of the Melbourne CBD.

She was named after her mother, and her father Richard was a cabinet maker.

Having such a large family, Eliza’s home would have always been full of people.

But her role in that home have greatly differed to that of her brothers.

Eliza’s samplers are one of the few fragments from the lives of 19th century girls that remind us of this fact.

Girls’ education

Girls spent a lot of time at home learning to do domestic tasks, like sewing, cooking, washing, and cleaning.

Their education was geared towards training them for womanhood and how to be good wives and mothers.

Needlework was a key part of this education, from working class to the wealthy.

It was seen as an essential feminine skill—plain sewing to make and mend clothing and household items, and embroidery to decorate them.

The content of Eliza’s sewing samplers shows us what she was being taught—carefully embroidered alphabets and numbers are common in needlework samplers from the time.

Yet these samplers also tell us that many girls never grew up to be women.

An unfinished sampler, likely Eliza’s own, is a poignant reminder of child mortality from a time when at least four out of every 10 Australian children did not make it to adulthood.

In 1852, the year before Eliza’s death, the Winter family also lost a son.

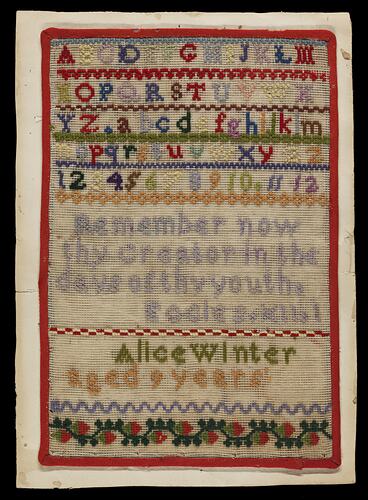

It’s perhaps for this reason that the youngest Winter, Alice—who was born several years after the deaths of her siblings—included the Ecclesiastical bible verse ‘Remember now thy creator in the days of thy youth’, in one of her own needlework samplers.

It points to her belief in a Christian God and her understanding that she, too, will one day die—a grim reality for a nine-year-old child.

But Alice was fortunate enough to live into her 80s.

The fact that these kinds of items have been kept long enough to end up in the museum’s collection is a testament to their importance.

Through the ages

Needlework samplers have been around since the 15th century, and had became a standard feature of a girls’ education by the 1700s.

Settler girls in Australia made cross-stitching samplers at school. Ten-year-old Beatrice Adams, a student at St Mary’s School in Hotham (present day North Melbourne) made a sampler in 1866 which is very similar to Eliza’s.

But samplers and other domestic items don’t tell us much about the lives these girls led outside the home.

Girls often worked out of home as domestic servants or in factories, went to school and played in the urban neighbourhood.

Some evidence of this can be found in the shape of homemade wooden dolls from archaeological digs around Little Lon—a working-class area in Little Lonsdale Street.

Girls even contributed to major public exhibitions, including the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition at the (now Royal) Exhibition Buildings—for which an 11-year-old Isabella McEwan crafted a seam and hem stitch sampler.

Items like these help piece together the story of what Melbourne girls’ lives were like in the past.

But there are still big gaps in our knowledge.

We have written correspondence, photos and paintings of prominent men and women from the era, but these rarely include much detail about children.

Of the hundreds of thousands of girls born in 19th century Australia, very little of what they made has survived.

What we do have are scraps in comparison to things made by today’s youth.

Eliza’s needlework samplers were treasured for nearly 170 years by generations of Victorians before they were acquired by the museum.

The significance of the items left behind by girls like Eliza is that they alert us to their presence—they are often the only reason we know anything about them.

They are a tangible and palpable link to girls' lives and stories.

With these samplers, girls have stitched their names into history—ensuring their memory lives on.