Eleven incredible meteorites

On 24 July 1969 the Apollo 11 astronauts returned to Earth with rocks from the surface of the Moon.

But what if they were not the most important rocks collected in the 20th century? What if they weren’t even the most scientifically significant rocks found in 1969?

In September of that year Professor John Lovering was disembarking a plane with Moon rock samples when a journalist presented him a plastic bag.

Within was a chunk of a meteorite that had just exploded above the northern Victorian town of Murchison.

When John opened the bag he was hit with a pungent smell similar to methylated spirits.

To the geologist, it was the unmistakable odour of organic molecules, including amino acids—the building blocks of our DNA.

On the spot, John declared it as ‘almost ... as exciting as Moon dust’.

But over the subsequent decades, its scientific prestige has only mounted from that first impression.

Fifty years later, Museums Victoria Dermot Henry says that innocuous-looking, remarkable-smelling black rock is now, probably, the world’s most studied meteorite.

The museum holds both lunar and martian rocks. But Dermot—a man who has devoted his life to rocks—ranks the Murchison Meteorite as his favourite in the collection.

Because this is a rock which may well harbour secrets of the formation of the Solar System, Dermot says. Its ‘exceptionally rare’ chemical composition—which gives the meteorite its distinctive smell—may well ‘offer clues to the origins of life’.

And all this from fragments of a rock which was picked up in cow paddocks.

‘Studying meteorites is the least expensive form of space exploration,’ Dermot says.

‘With meteorites, the samples come to us.’

The Murchison is just one of many strange and storied space rocks held by Museums Victoria. Below are 10 others—as well as one which disappeared.

The Maryborough Meteorite

The Murchison is the only known meteorite to be witnessed and collected in Victoria.

But there have been 16 other meteorites recorded in the state. These were found, often many years after crash landing. Of those, the Maryborough is the most recent.

It was found by David Hole, in May 2015. The local prospector was sweeping for gold with a metal detector when he hit upon the 17-kilogram hunk of rock.

David knew he’d struck something unusual. He just had no idea what on Earth it was. So, as any good handyman would, he took it into his shed to figure it out.

The result of David’s investigations were a few drill marks and a suspicion or two, but nothing concrete.

Three years later, still searching for answers, the Maryborough man brought it into the Melbourne Museum.

Dermot and the museum’s emeritus curator in geosciences, Bill Birch, were used to pouring cold water on the discovery of what they’ve dubbed ‘meteor-wrongs. But both knew, instantly, that this was different.

They then began the process of scientifically identifying it, with their work published in July 2019.

Read more about its 4.6 billion year history here.

The Pigick and Rainbow meteorites

Few people are fortunate enough to accidentally discover a meteorite in their lifetime. Fewer still do so twice. Then there’s a whole new category of niche for people like Wimmera wheat farmer Daryl Wedding.

In the ploughing season of 1994, Daryl uncovered two wildly different meteorites—in the same field. One was named Pigick after the local parish, the other Rainbow after the nearest town. Daryl donated both to the museum.

Like the Maryborough and Murchison, both the Wimmera meteorites are stony meteorites. But, within that type, meteorites are broken down into further classes, according to the silicate and metallic minerals that make them up. And the ‘meteoric DNA’ of the Rainbow’s is exceptionally rare.

It is classed a CO3 carbonaceous chondrite—the chondrites being among the earliest of physical substances to form in the soup of the early Solar System, crystals upon which the rocky planets formed billions of years ago.

‘Chondrites are telling us how the early Solar System formed,’ Dermot says.

'These chondrules probably represent small spherical droplets of liquid which condensed out of the gaseous solar nebulae, then these droplets crystallised.

'These spheres then clumped together to form little rocky bodies which snowballed growing bigger and bigger to become planet sized in some instances.'

The Cranbourne Meteorite

The first meteorite discovered by the colonists of Victoria was the Cranbourne, though the First People of the area long knew of its existence.

The colonial record speaks of First People ‘danc[ing] around the meteorite, which was almost completely buried, beating with their stone tomahawks against it, apparently most pleased with the metallic sound it produced.’

Though unaware of its otherworldly origins, the early colonists were also drawn to the strange rock. In order to promote the area in 1854, one made a horseshoe from the iron meteorite. The enterprising residents wanted a train to pass through Cranbourne and some proposed the meteorite might be an iron ore deposit. Unfortunately, the whereabouts of this extraterrestrial piece of equine footwear is unknown.

In 1860 an amateur geologist recognised the rock as a meteorite and this discovery went on to make the Cranbourne an international sensation. At the time, it was the largest iron meteorite in the world. More of its fragments would be unearthed for decades to come, with the combined weight of its known specimens weighing in at more than 8.5 tons.

The most recent fragment was found in 2008 near Clyde, by students form the Clyde Primary school.

Tektites

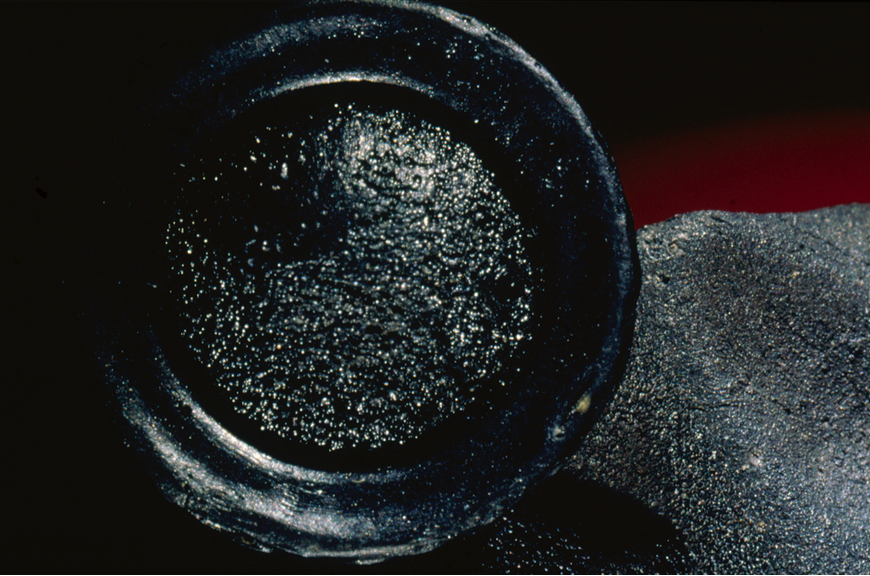

Parts of Victoria abound in glassy black rocks which take on enigmatic forms likened to disks, buttons, dumbbells and ladles.

For more than a 100 years of the state’s colonial history, theories swirled about the origins of strange and alluring rocks. Many thought they emerged from Victoria’s volcanoes, others that they were a fusion of dust and lightning in the atmosphere. Some believed their origins were extraterrestrial.

Today we know that tektites are formed when an asteroid hits Earth, shooting molten material into space, where it rapidly cools and falls back to Earth. As it re-enters the atmosphere, its exterior melts and is sculpted into its varied forms.

'Tektites are a form of impact glass,' Dermot says.

The asteroid which created Victoria’s tektites remains a mystery, but it is likely to have struck somewhere around what is now Cambodia and the impact zone would have been very large, perhaps more than a 1-kilometre wide.

The tektites would have fallen across south-east Asia and Australia in a single event, like 'hailstones of glass' Dermot says, with the best preserved buttons and shapes along the Port Campbell coast.

'NASA got interested in these as the buttons must have stayed stable in flight during re-entry of the atmosphere,' Dermot says.

'They used the shape to model the re-entry heat shields on the Apollo return modules.'

So while not actually meteorites, there would be no tektites without rocks from space.

Lunar meteorites

The museum does hold one Moon rock, but it wasn’t collected by astronauts. It came to Earth of its own volition. This lunar meteorite has a similar origin story to the tektites.

‘The Moon has been massively bombarded over 3.5 billion years by meteorites big and small,’ Dermot says.

‘And there is no atmosphere there to slow them down or burn them up, so everything just smacks into the Moon’s surface.’

Bits of the Moon are then blasted from the surface and the Moon's lower gravitional pull means there is little to slow them down on their upward trajectory either. If the meteorite is big enough, the lunar rocks can be blasted all the way to the surface of the Earth.

Many look very similar to Earth rocks. But, as is the case with the museum’s rock, a volcanic piece of basalt, there is often one major give away.

‘It’s about 3.3 billion years old, but you look at it and the rock is as fresh as what you see in a new lava flow in Hawaii,’ Dermot says.

‘There is no weathering on the Moon.’

It is believed to have spent 80 million years in orbit before crashing into Earth.

The museum has an Apollo mission Moon rock on loan.

Martian meteorites

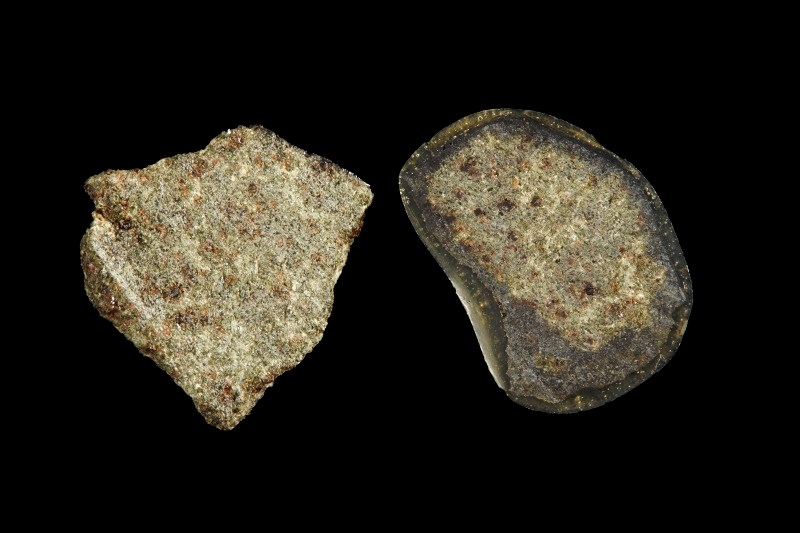

The museum has five rocks from Mars, which have an almost identical origin story to the lunar rock.

The difference being that Mars has a strong gravitational pull and is much farther away.

So it takes a very large meteorite to blast chunks of Mars all the way to Earth—martian meteorites, therefore, are much rarer.

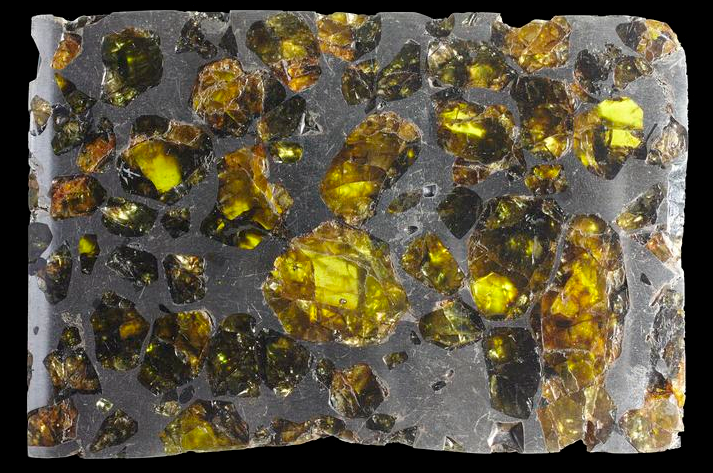

The Esquel Meteorite

Most of the meteorite specimens in the MV collection were collected in Victoria. And not all of them have purely scientific value. Some happen to be utterly gorgeous too.

Found in Argentina in the 1950s, the Esquel Meteorite is a rare stony–iron pallasite—and one of the world’s most beautiful meteorites. Museums Victoria holds a handful of Esquel specimens.

‘Esquel is beautiful, Dermot says.

‘The olivine crystals in it are gem quality.’

Olive is known as the birthstone peridot. The gemstones in the Esquel would have celebrated that milestone more that 4.5 billion times.

The Bencubbin Meteorite

To a geologist, a meteorite is not just a conglomerate of minerals, but a story. Few tell as dramatic a story as the Bencubbin Meteorite. According to a popular theory, it is the story of an interstellar, high speed collision, frozen in time.

‘It looks like big blobs of black rock trapped in metal,’ Dermot says.

‘Basically, people think what is now Bencubbin was two asteroids of very different composition that collided and smashed each other apart.

‘In that enormous release of heat and energy all those pieces have collapsed in together again and formed a mixture of the two.

‘So the blobs carbonaceous chondrite material, similar to Murchison, while the metal is the iron core of a large asteroid.’

Found in Western Australia, the Bencubbin is so unique it forms a category of meteorites called Bencubbinites.

The museum holds a specimen of the Bencubbin Meteorite.

The Wedderburn Meteorite

Some meteorites not only look different to Earth rocks, they also contain alien minerals.

The Wedderburn Meteorite was discovered in 1951, but it wasn’t until decades later that it was revealed to have a new iron carbide mineral, dubbed 'Edscottite' or Fe5C2.

It is believed the mineral was forged in the molten core of an ancient asteroid long since destroyed, and then strewn across the solar system.

But as the Wedderburn Meteorite is about the size of a lemon, and the only known source of Fe5C2, it may be the rarest mineral in the world.

The Missing Meteorite

Of the three main types of meteorites, stony-irons are far and away the most rare. Of Victoria’s 17 known meteorites, just one falls into this group.

The Bendoc Meteorite is believed to have been discovered by gold miners in 1898 in East Gippsland. Being close to the border, it was sent to the New South Wales Department of Mines for examination and, in 1902, was described as a stony-iron pallasite.

Unfortunately though, from there the trail goes cold. If it was preserved, no one knows where it is.