Audio-Visual Material in the Kodak Heritage Collection at Museums Victoria

This audio-visual material in the Kodak collection is evocative and valuable in the study of Kodak’s history. It provides unique content that doesn’t exist in the still photographs in the collection.

The Kodak Heritage Collection

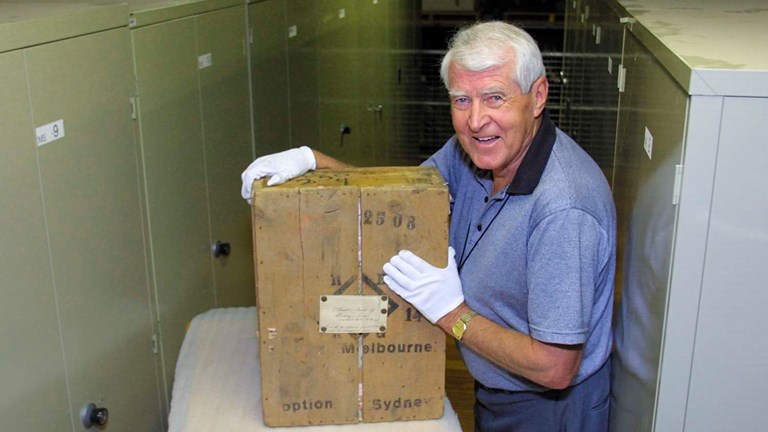

Around 12 years ago I acquired a collection for Museums Victoria which I am still very passionate about, and am still working on – the Kodak Heritage Collection.

Kodak Australasia’s history reaches back over 100 years. The company was established in 1908 when Eastman Kodak merged with Baker & Rouse, but the Baker & Rouse story stretches back even further to 1884, when Thomas Baker first founded his pioneering photographic manufacturing company in the Melbourne suburb of Abbotsford. Kodak Australasia’s long history of photographic manufacturing came to an end in 2004 when its Coburg factory closed down. Before the factory site was vacated, Museums Victoria worked closely with the company to acquire a large and significant material culture collection, known as the Kodak Heritage Collection.

This collection is nationally significant, and is extensive in size and scope. It is still being registered, but consists of over 40,000 items, which record the history of the company’s manufacturing, marketing, educational, retail and working life activities around Australia, with an emphasis on Melbourne. As well as over 30,000 photographs and slides, 6,400 documents, and 3,300 objects, the Kodak Heritage Collection incorporates a substantial and diverse audio-visual component of over 780 items dating from the late-1950s to the early 2000s.

A Treasure-Trove of Audio-Visual Material

The audio-visual material includes over 360 reels of 16mm motion picture films, (of which 134 have been digitized to create low resolution access files), over 170 video cassettes, over 100 examples of 35mm slideshow sets including 27 with audio cassette tapes and 20 with booklets or scripts, about 10 born digital video files on DVD and compact disc, and about 50 born digital oral history interviews.

This audio-visual material is evocative and valuable in the study of Kodak’s history. It provides unique content that doesn’t exist in our still photographs - even though we have thousands of still images in the Kodak collection. The audio-visual material is also visceral and imbued with narrative. It gives us a different level of historical immediacy and intimacy than still photographs. It provides motion - we don’t need to imagine what came before or after, as we do when a single moment is captured by a still photograph – we can view a sequence of events, and see a narrative unfold. Audio-visual material also can, but does not always, bring sound to the scene, providing another sense with which to experience history.

Of course, this material must always be interrogated in terms of its original aims, its producer, its intended audience, its biases – the veracity of all visual material must be critically assessed. Nonetheless, with rigorous framing, our audio-visual material is of great use to the curators and historians of Kodak’s history, and to our public audiences who wish to learn more about the company’s history in Australasia.

Of particular importance in the Kodak audio-visual collection are the 200 or so Australian TV commercials in 16mm film format, which date from the late 1950s to the 1970s; over 100 slide educational lecture sets from the 1960s to the 1970s; the handful of examples of rare documentary footage of the company’s factory and processing sites in Melbourne which date from the 1960s; and the 50 oral history interviews recorded in the 2000s by museum staff.

Television Commercials

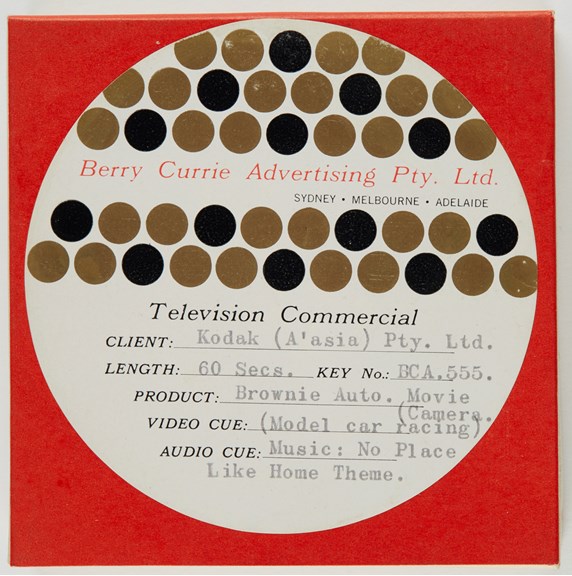

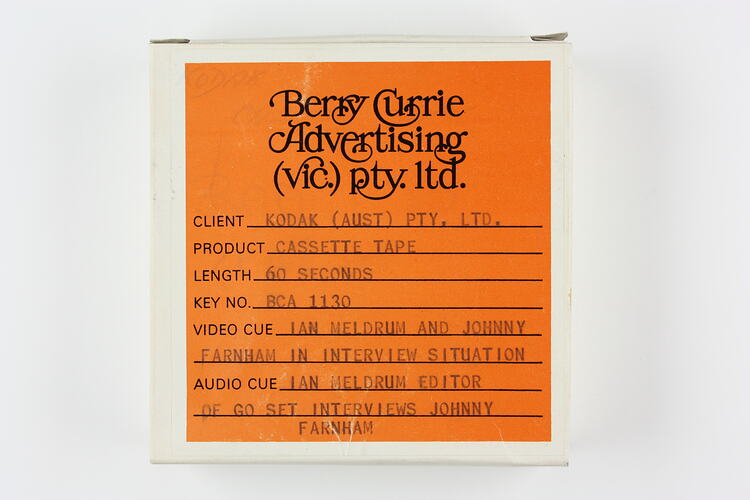

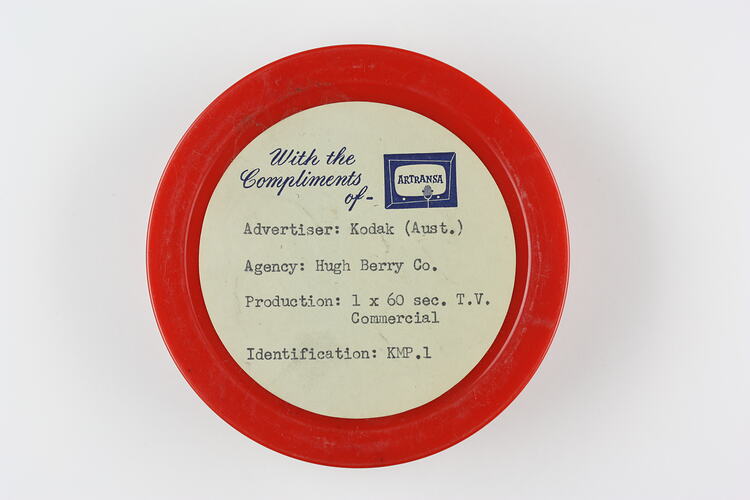

Almost 60 of the 200 TV commercial films we hold have been digitised, and while they may be short, only 30-60 seconds, these mid-century TV commercials are packed full of important historical information. As well as showing us information about Kodak - the products, the camera technology and film chemistry of the time - these commercials are also a window into the social values of the period, in particular gender roles, cultural stereotypes and the role of children in society.

These commercials are also a lens into the embryonic television industry of the period, and additionally are a record of Australia’s advertising and film production companies. Most of the commercials were produced by Berry Currie Advertising - a Melbourne-based advertising agency. We can glean from the film reel packaging that Berry Currie worked with a wide variety of Melbourne and Sydney based film production companies to produce the commercials, including Fanfare Films, Senior Film Productions, Browning Studios, Cambridge Film and TV Productions, Aranda Film Productions, and Bilcock and Copping. Many of these were private companies run from television stations, for example Channel 9’s Television City in Richmond. From the late 1960s to early 1970s there was a surge in these local film production companies in response to the growth of the television industry, and many of these companies are represented in Kodak’s collection.

Lecture sets

The Kodak collection includes over 100 slide lecture presentation sets, 27 with audio cassette and 20 with typed booklets or scripts, dating from the 1960s to the 1970s. One important group of these lecture sets were designed to teach consumers and photographic enthusiasts about various elements of photographic practice, such as ‘composition’ or ‘flash photography’. As such they represent how Kodak provided an important educational role for the Australian public, albeit always imbued with a marketing message to sell Kodak product. Another key group of the lecture sets featured slides of entries in photographic exhibitions from around the country that were mounted by local photographic societies or by Kodak. These sets worked to build the role of amateur photography in Australia and portrayed it as a worthy artistic pursuit.

As well as containing content, these lecture sets represent a key 20th century technological moment, when the presentation of audio-visual material relied on analogue technology. The Kodak collection includes equipment used to view this analogue audio-visual content, from simple 35 mm projectors with carousels, to the sophisticated ‘Multivision’ presentation system that engaged multiple projectors to present multiple formats including still images moving footage, and sound.

Documentary footage

The most significant audio-visual material in the Kodak collection for me, however, is the 16mm film footage of Kodak’s Australian manufacturing and industrial operations at Coburg and Burnley in the 1960s. This footage is rare - there are only a handful of examples, all of which are silent – and the content is extraordinary and compelling to watch. These examples mark important milestones in the evolution of the company, when Kodak was transitioning to its new Coburg factory from its manufacturing site at Abbotsford and from its photo-chemical and film processing plant at Burnley.

The footage that we hold shows us the operational workflow of photochemical product mixing and packing, photo-processing and printing. It also shows us a wide range of work undertaken at the large and complex enterprise at Coburg, including office, distribution and transport work. However, it must be noted that the Kodak factory moving footage material is skewed to the representation of particular types of activities, namely those normally undertaken in white light. There is a lack of visual representation of the company’s core business of emulsion making and coating work, and film developing. This gap also exists the still photographs in our collection, and can largely be explained by the fact that photographic products are light-sensitive and manufacturing and processing must be done in the dark or safe-light conditions, so you couldn’t easily film this particular type of work. Also, there was strict industrial confidentiality around the manufacture of Kodak’s emulsion based products – this protectionism was known in the US as the ‘silver curtain’– and it was likely to have restricted the visual documentation of the manufacturing process. Despite its restricted focus on only some work at Kodak, this footage is nonetheless very significant and allows us to understand more about Australia’s photographic manufacturing industry.

In addition, the footage is not just useful for those interested in Kodak or photographic manufacturing – it is also a great resource for scholars examining broader fields such as labour history, urban history, gender studies and cultural diversity. It highlights the manual and hazardous nature of some of the work, and safety practices used in the factory. It tells us about the architecture, layout and technology of the factory, and the optimism of the company. It locates the factory in its landscape, suggesting the ongoing tension between industry and residential space on our urban fringes. It also gives us insights into the demographic and diversity of the workforce, the division of labour in terms of which tasks were allocated to women versus men, the cultural composition of the labour force, and who was absent in the workforce.

Oral History Interviews

The Kodak collection also includes about 50 important oral history interviews recorded by myself and other Kodak team members in the 2000s. These digital audio recordings are in wav (preservation) and mp3 (access) formats, and have all been transcribed. The content in these interviews tells us about the working lives of former Kodak staff, and in a few cases, families who owned land on which Kodak’s Coburg factory was built. These interviews provide a lot of rich detail about the nature of work at Kodak over time, including information that we would simply otherwise not know as it doesn’t exist in the written or visual archival record. The interviews also provide information about the education and socio-economic background of staff. As such, this audio material is significant for a broad range of reasons, and in an increasing number of cases the interviewee has now passed away, rendering their testimony even more precious and rare.

Conclusion

Audio-visual material has had a critical role in providing context to the history of Kodak Australasia. However, accessing its content to facilitate this has not been simple. We have been lucky to have funding for a technician to digitise some of our motion film at low resolution, as well as to apply a ‘preservation wind’ of the film onto an archival core for long term storage in our cool store. This digitisation work has enabled us to view the content of this particular format, often revealing stunning and significant audio-visual content we didn’t know was there, as not all of our motion film was labelled and even if it was we couldn’t necessarily visualise what a particular title was.

However, we have not yet been in a position to view all of our motion film, nor view our video tape material or listen to our audio cassettes, let alone digitise them, and it has also not been possible to digitise all of our thousands of 35mm slides. Hence, a considerable amount of historical information is physically locked into the collection material until we have the means to digitise and document it in future.

In addition, without the contributions of our community of former Kodak staff, historical information about digitised content that we could see might also have been locked in. We have relied on the technical expertise of the former Kodak workers to understand particular work processes and identify locations in the footage. Without their input, our understanding of the collection would be diminished.

I am grateful to Kodak Australasia for preserving their audio-visual material for so many decades before it was acquired by Museums Victoria, and I am also grateful for the longevity in my role which has allowed me to delve into the collection and the company history in depth. I look forward to viewing more of this material as time goes by - always with a critical contemporary eye to its content and original aims and audiences – and making it accessible to bring Kodak’s history alive for future generations.

i Thanks to former Kodak Heritage Collection staff member Hannah Perkins for providing the research about the Kodak TV commercials. Thank you to Lesley Alves who conducted many of the interviews with Kodak staff.

This article was first published in the Australian Society of Archivists Victorian Branch August newsletter. For more information about the Kodak Heritage Collection visit Museums Victoria Collections.