125-million-year-old footprints rewrite the history of birds in Australia

Ancient bird tracks found on Australia’s southeast coast, could be the oldest evidence for avian dinosaurs in the Southern Hemisphere.

Footprints found on Australia’s southeast coast, are the earliest evidence of birds in the Southern Hemisphere.

27 avian footprints have been dated to be between 120 and 128 million years old, from the Early Cretaceous period when Australia was still linked to Antarctica.

‘We don’t have much knowledge of birds in Victoria at his time,’ says Dr Thomas Rich, curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Museums Victoria Research Institute.

He is a co-author of the new study published by an international team of researchers in PLOS ONE.

‘These footprints are adding to that picture of biodiversity of the Early Cretaceous,’ says Tom.

‘I’ve always felt that my contribution, after 50 years of palaeontology, is to find what’s here.

‘When you find a footprint, you know the organism that made it was right there.

‘A bone can be moved, but a footprint stays.’

Because these bird footprints were scattered amongst those made by dinosaurs, it was initially difficult to identify what they were.

‘At first I thought the tracks might have been made by young theropods,’ says the study’s lead author, Dr Anthony Martin, a palaeontologist from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

‘But I soon realised they were bird tracks.

‘Most of the bird tracks and body fossils dating as far back as the Early Cretaceous are from the Northern Hemisphere, particularly from Asia.

‘Our discovery shows that there were many birds, and a variety of them, near the South Pole about 125 million years ago.’

A rare find

The picturesque stretch of coastline southeast of Melbourne, is known for a rich history of dinosaur-aged discoveries.

It is the source of Australia’s first dinosaur fossil and Victoria’s state fossil emblem, Koolasuchus Cleelandi.

But fossil evidence of birds is scarce compared to remnants of larger animals.

‘We’ve got 10 feathers from Koonwarra (about 20km from where the footprints were found),’ says Tom.

‘They’re miniscule and only a few millimetres long; the birds that made these footprints are much bigger.’

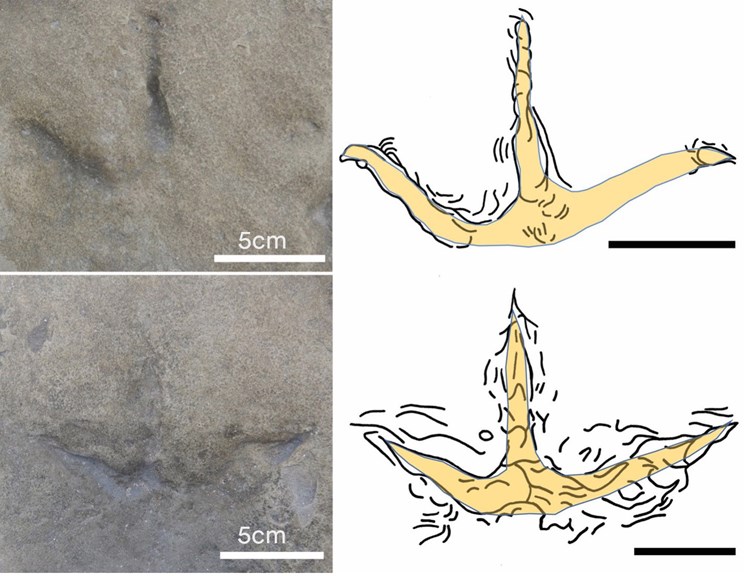

These footprints range in size between seven and 14 centimetres wide—comparable to the tracks left by modern day shorebirds, like small herons.

And their location in the layers of rock on the coast suggests that these may be evidence of a migratory route during the polar summers.

Just two Early Cretaceous period footprints have previously been discovered in Victoria, on the Otway Coast in the state’s southwest.

In 2013, Anthony dated those at around 105 million years old making this latest find the oldest record of birds in Australia.

To verify the new footprints’ avian origins Anthony studied the relative proportions of the tracks.

Birds are thought to have evolved from theropods—a group of two legged carnivorous dinosaurs that includes Australovenator and Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Despite the common ancestry, the impressions of the toes in the more recent set of footprints were too thin and spread too far to belong to dinosaurs, and some also had rear toes to give them away.

Finding the footprints

The footprints were discovered by a volunteer, Melissa Lowery, who has found hundreds of fossils left by dinosaurs, and now ancient birds, along the foreshore.

The footprints were likely made by animals stepping into mud or soft sand in a rift valley, crisscrossed with rivers.

The footprints were preserved when the river flows were covered by sediment.

Once back at the surface, though, these footprints are difficult to spot and don’t last long.

‘Those footprints have been around for over 120 million years and just for a tiny amount of time they’re visible before they are lost forever,’ says Tom.

Many of them are only visible at low tide and are rapidly being eroded by natural forces.

Seven of the tracks found by Melissa have already been lost.

‘You want to document as many good ones as you can—and that’s what we’ve done,’ says Tom.

‘You have to be ready to take advantage of things like this when they happen.

‘It’s serendipity, you can’t predict it.’

Museums Victoria and the Dinosaur Dreaming group have also developed methods to record these fleeting footprints.

One tactic is to take a series of photographs to build up a highly detailed 3D model, known as photogrammetry.

Another is to cast the footprints in silicon, which can then be reproduced in resin and fibreglass, preserving fine detail from the original.

These records are kept at the museum, preserving them for future generations.