Skynotes: October 2022

Upcoming events

Welcome to October Skynotes for a month’s worth of data, dates and night sky information. We revisit some fascinating topics covered this time last year adding extra links and content, but first this latest news from James Webb Space Telescope some 1.5 million km out in space…

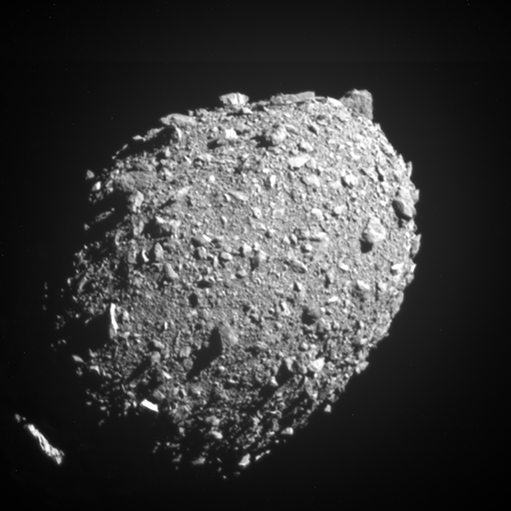

Haloed orb in the darkness of space

Image: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

Jupiter was astonishing in images in August and now here is Neptune appearing as a shimmering orb in the darkness of space with an ethereal halo amid hovering sprites. This is a Near-infrared Camera image of the planet, its rings and seven of its 14 known moons (bright Triton was seen above and to the left but is not included in this cropped shot). It is another stunning example of the power and sensitivity of this new telescope when trained on objects within our solar system.

Delve into:

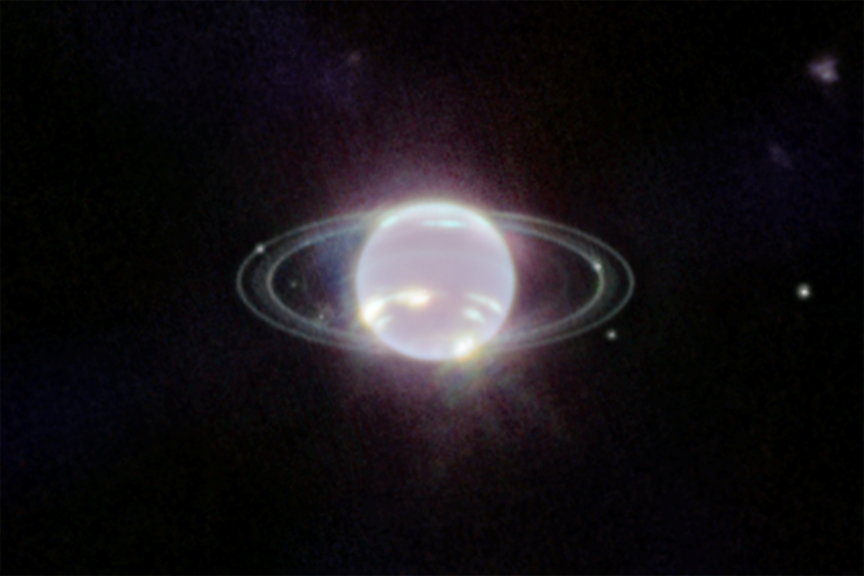

DART dives into Dimorphos

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) has impacted its planned target, the small asteroid moonlet Dimorphos (160 meters in diameter) which is in close orbit around larger parent asteroid Didymos (780 meters). The pair make an elliptical orbit around the sun every 2.11 years at a distance that varies from a little over 1 AU out to 2.27 AU (or Astronomical Units which is the average Earth-Sun distance).

The DART impact technique is designed to test the concept of altering the orbit of one, ever so slightly, with respect to the other. As the results are analysed this is expected to provide valuable data for any future mission that might try to ‘nudge’ a potentially Earth-threatening asteroid into a safer orbit around the sun well ahead of time so it will safely miss our planet.

Learn more:

Melbourne Sun times

| Date | Rise | Set | Day length | Solar noon§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturday 1st | 5:56 | 6:24 | 12:27 hrs | 12:09 |

| Tuesday 11th | 6:41 | 7:33 | 12:51 hrs | 1:06 |

| Friday 21st | 6:27 | 7:42 | 13:15 hrs | 1:04 |

| Monday 30th | 6:14 | 7:53 | 13:38 hrs | 1:03 |

§ When the sun is at its highest, crossing the meridian or local longitude.

*Australian Eastern Daylight Time (AEDT) begins at 2am on Sunday 2nd.

Moon phases

| Date | Phase |

|---|---|

| Monday 3rd | First Quarter |

| Monday 10th | Full Moon |

| Tuesday 18th | Third Quarter |

| Tuesday 25th | New Moon |

Moon distances

Monday 17th is lunar apogee (furthest from Earth) at 404,328 km.

Sunday 30th is lunar perigee (nearest to Earth) at 368,290 km.

Planets

Mercury is approaching its passage around the sun and will not be visible this month. It will return to our evening skies in December at dusk in the south-west.

Venus is also about to disappear behind the sun but will be back in the evening in our western skies early in January.

Mars is getting close to opposition, opposite the sun as seen from Earth. It is a morning planet visible in the north-east from 1am and will then be lost in the early morning light shortly after 6am.

Jupiter too is nearing opposition. It can be seen brightly in the eastern sky from 8pm and will then move during the night across the north and drop below the western horizon shortly after 5am.

Saturn is visible from 10pm in the north-east and it too will traverse the north until by 3am it will be lost low down in the west.

Meteors

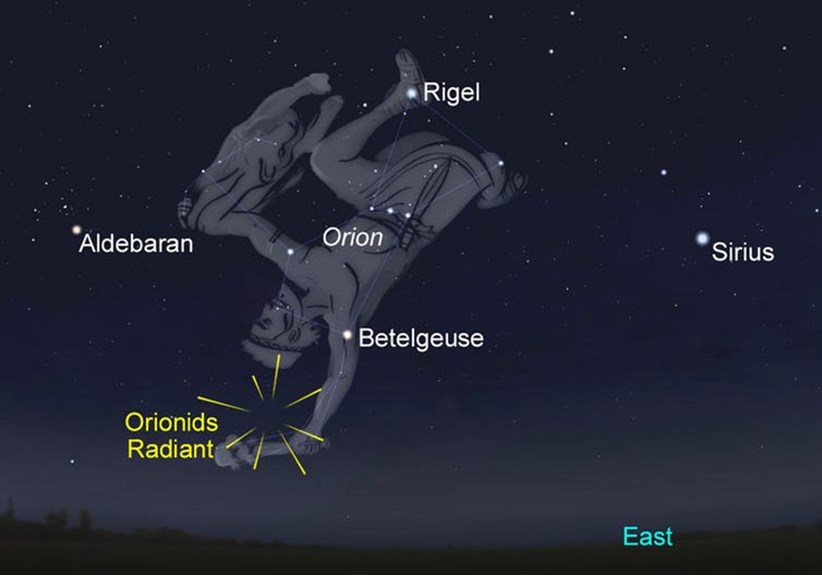

The Orionids are visible from the 15th-29th but peak on the 21st-22nd with estimates of around 30 meteors per hour. The best time will be from around midnight until early dawn. The shower is centred on Orion the Hunter near the red supergiant star Betelgeuse. These meteors are typically very fast and bright. They enter the atmosphere at about 66 km per second and vaporise 100 km above the surface leaving persistent trails in the sky. The Conversation has a detailed guide by Dr Tanya Hill and Professor Jonti Horner.

Humans have observed and marvelled at meteor showers and comets throughout recorded history but the connection between specific meteor showers and comets is a recent understanding. For some ancient cultures they were omens or messengers. The Orionids shower was first recorded by the Chinese in 288 AD and is associated with Comet Halley.

That famous comet is named after Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley. In 1705, after studying earlier records of certain comets that seemed to re-occur and applying Newton’s new laws of motion, Halley calculated its elliptical orbit around the sun and successfully predicted its return in 1758 (which sadly he did not live to see).

Comet Halley orbits the sun every 75 years on a path that takes it out beyond Neptune. Each time it passes through the inner solar system it leaves in its wake a trail of particles for our planet to pass through. Twice a year Earth intersects the comet’s previous orbits and we enjoy these meteor showers - the Eta Aquarids in April-May and the Orionids in October. In 1986, during it last visit to the inner solar system, Comet Halley was observed from telescopes and a flotilla of space probes.

This photo by the International Halley Watch was taken on 8 March 1986 and shows a broad dust tail and below it a faint ion tail both emanating from the coma or head of the comet, deep within which lies the nucleus itself. As the comet enters the inner solar system heat from sun warms the 5.5km rocky-icy nucleus and cometary particles are vented and blown away by the ‘solar wind’ – the constant stream of photons and sub-atomic particles such as protons given off by the sun. The comet’s tails always point away from the sun, not following strictly behind the comet in its orbit.

Enjoy a close encounter video compilation by ESA’s Giotto FlyBy. While Comet Halley’s next appearance is not due until July 2061, twice every year we can enjoy Orionids and Eta Aquarids as reminders of its former passes through the inner solar system.

And Taurids as well…

Another meteor shower that could be enjoyed late this month, although less impressive than the Orionids, is the Taurids linked to Comet Encke. This is a long duration shower in Spring that actually peaks in the first week of November. There are two branches - one near the star cluster Pleiades, and the other close to the red star Aldebaran in Taurus - each giving 10 meteors per hour that can be bright and slow with colourful fireballs.

Learn more:

Stars and constellations

In the north

As the year progresses we see Aquila (the Eagle) and its principal star Altair (Alpha Aquilae) directly north but Lyra (the Lyre) and its bright star Vega (Alpha Lyrae) have left our northern skies this month.

In the west

Scorpius is now moving down to the west with the red-giant star Antares the middle of three stars that mark the scorpion’s body. High above following the scorpion is the asterism ‘the teapot’ which gives you the position of the bow and arrow held by the centaur Sagittarius.

In the east

Formalhaut in Piscis Austrinus (Southern Fish) is the bright evening star in the east this month. But as spring ends and we move towards summer we will progressively begin to see from the north-east around to the south-east the beautiful Pleiades cluster, Taurus the bull and Aldebaran, Orion the hunter with the ‘saucepan’ and Betelgeuse, and Canis Major and Sirius. See our Stellarium screenshot of the Orionids Meteors looking east from 1am.

In the south

If away from bright lights you can see in the south-east the isolated Large and Small Clouds of Magellan (our galaxy’s nearest neighbours) as well as the vast band of billions of stars and dark dust clouds that make up what we can see of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. In the evenings this month it runs in a broad arc from south to north. From our location about 28,000 light years from the centre of our disc shaped galaxy we have an edge-on view along the plane of the galaxy where the density of stars is greatest. As you look away from the Milky Way to either side of the sky you see far fewer stars. In those directions you are peering through only a thousand or so light years out into intergalactic space, to the north or south of the galactic plane. Being inside something in the dark doesn’t help much in trying to work out its size or shape! Where we are in the galaxy and its size and shape was not fully understood until quite recently.

Low in the south-west are the Pointers, Alpha and Beta Centauri, in the constellation of Centaurus (the other centaur in our night skies). Following the line of the two bright Pointers lower to the horizon leads to the small but famous Crux (Southern Cross). Crux and the Pointers are among many southern hemisphere stars that are circumpolar - from our southern latitude they trace curving paths through the night and are always above the horizon.

Circumpolar means ‘around the pole’

As our planet rotates some stars rise in the east and set in the west during the night – that’s diurnal motion, the daily turning of the Earth. It is the same reason why the moon, the planets and the Sun all appear to rise in the east and set in the west. But stars that are far enough south (or far enough north in the northern hemisphere) take half-circle paths during the night remaining above the local horizon at all times. They never set and complete their circular journey during daytime when they can’t be seen.

However, there are two extremes of this ‘around the pole’ motion. At the south pole’s months-long winter no stars rise or set, all remain above the horizon, all are circumpolar. But, at the equator stars are all seen to rise and set during the night, none are circumpolar.

A fixed camera set for a long exposure can record trails of stars making curving paths across the sky during the night. Such paths are centred around the South Celestial Pole (SCP), the point around which the stars appear to turn as Earth rotates. The SCP represents the position in the southern sky our planet’s axis of rotation points to. At the South Pole which is latitude 90 degrees south it would be above at the zenith (the point above your head), but from Melbourne’s latitude of 38 degrees south the SCP sits 38 degrees above the southern horizon (which is 52 degrees away from the zenith).

See:

A photo like this also shows how trails bring out the colours of the stars as their photons of light accumulate over the long exposure. Colour relates to surface temperature with the hottest stars seen as blue-white, less hot as yellow, and lowest in temperature being red.

Find out more:

International Space Station

At a distance of about 400km the ISS completes an orbit every 90 minutes and appears as a bright point slowly moving across the night sky. Here are some of the brightest passes expected this month over Melbourne:

Morning

Monday 10th 5:54am-6:00am South-West to North-East

Thursday 13th 5:05am-5:10am South-West to North-East

Evening

Friday 14th 8.54pm-8.58pm North-West to East

Monday 5th 8.03pm-8.10pm North-West to South-East

Heavens Above gives predictions for visible passes of space stations and major satellites, live sky views and 3D visualisations. Be sure to first enter your location under ‘Configuration’.

On this day

3rd 1942, first object to reach space, the experimental V2 (‘Vengeance’) rocket, was launched from Peenemünde, Germany in a brief flight over the Baltic.

4th 1957, Sputnik (USSR) was launched to become the first artificial satellite.

4th 2004, SpaceShipOne was launched as the first private spacecraft into space.

5th 1923, Edwin Hubble (USA) established that M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, is separate to our own Milky Way Galaxy.

7th 1959, first photos of the moon’s far side are taken by Luna 3 (USSR).

9th 1604, a Type1A supernova 20,000 light years away in constellation Ophiucus is visible from Earth, and on 17th Johannes Kepler observes and publishes his account of the new star. It is the most recent supernova visible to the naked eye in our galaxy.

10th 1967, the United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty on the peaceful exploration and use of space was established. By now 109 nations are signatories and several other agreements and conventions have been created to cover space law.

11th 1958, Pioneer 1 (USA), a battery- powered probe aiming for lunar orbit, fails to reach escape velocity and burns up.

11th 1968, first crewed Apollo mission, Apollo 7 (USA), launched into Earth orbit in test of Saturn V rocket and Command and Service Module (CSM).

12th 1964, USSR’s Voskhod 1 (‘Sunrise’) was the first spacecraft with a crew of more than one. In this case, three cosmonauts who orbited for 41 hours.

13th 1773, the Whirlpool Galaxy M51a, 31 million light years away in constellation of Canes Venatica, is discovered by astronomer Charles Messier.

18th 1967, Venera 4 (USSR) is the first probe to analyse the atmosphere of another planet when it does so at Venus.

19th 1910, birth of Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar who had major insights into stellar evolution and black holes.

24th 1998, Deep Space 1 (USA) probe was launched to test innovative technologies, including an ion engine, while visiting Asteroid Braille and Comet Borrelly.

27th 1994, first sub-stellar object orbiting a star is found, a brown dwarf at Gliese 229.

29th 1991, Galileo probe (USA) is the first to visit an asteroid, Gaspra 951, on its way to Jupiter.

31st 2000, Expedition 1, first resident crew of the International Space Station, arrived by a Russian Soyuz craft for a 136 day stay lasting until March 2001. The three-person crew (one American and two Russians) made the station fully operational, hosted three visiting US Space Shuttles, and received two Russian Progress supply vehicles.