First Peoples of Australia Astronomy

There is no single First Peoples astronomy. As with all other areas of First Peoples culture, astronomical traditions vary largely across the country, especially between different language groups. Nonetheless there are some features which are common to many local astronomical traditions that are quite different from European traditions.

Differences with European traditions include:

- The prominence of dark nebulae (the dark patches in the sky, such as the Coalsack near the Southern Cross).

- The prominence of star colours.

- The shapes of constellations. Many First Peoples traditions included constellations on a basis other than figurative representation, instead using more abstract relationships such as the position relative to other stars.

- For almost all First Peoples groups, the Sun was seen as a woman and the Moon as a man.

Similarities with European traditions include:

- At least some regions made the distinction between stars and planets.

- Knowledge of the celestial pole, and circumpolar stars.

- Observations of events such as eclipses, comets, meteors and aurorae.

Like other cultural traditions, Astronomy was not important for its own sake, but was integrated with other forms of knowledge.

- Astronomical shapes were often understood to have their counterparts in the landscape.

- Events seen in the sky could be premonitions or messages about human events.

- Seasonal changes in the stars reflected seasonal changes on the ground.

Stars were not generally used for navigation purposes by our First Peoples. Navigation over land was extremely important and navigation skills were generally highly developed. However, most groups rarely travelled overland at night, except when undertaking secret or important missions. In these cases stars were known to assist navigation.

An important exception was the marine navigation of First Peoples mostly in northern Australia. Some of these societies had quite developed astronomical traditions for navigation.

Like many other cultural traditions, star stories were generally divided into male and female traditions. Stories could also be divided along moiety lines. (Many First Peoples societies were divided into two classes called moieties; every person and most animals and objects belonged to one or other of these.)

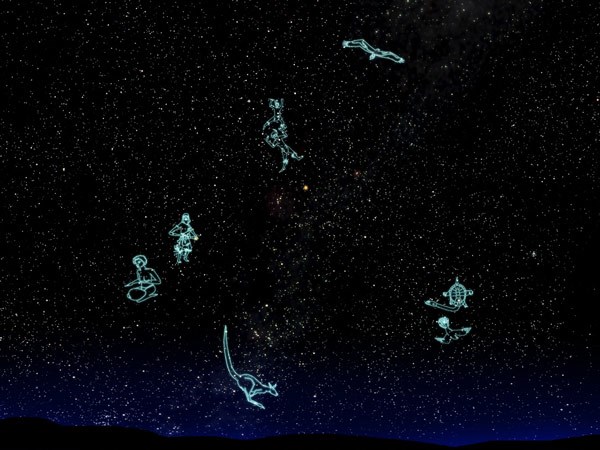

Constellations from stories in the stars: The night sky of the Boorong people

Bunya (Bun-ya)

Bunya, the possum can be seen in the constellation known to us as the Southern Cross. The tip of the Southern Cross is the nose of the possum and his tail hangs down to the left. Bunya ran away from Tchingal, the Emu and hid in a tree for so long that he turned into a possum.

Warepil (Wah-re-pil)

The brightest star in the night sky is called Sirius and it is the centre of one of the most important Boorong constellations. Warepil is the male wedge-tailed eagle and chief of the Nuh-rum-bung-goo-tyas, the elders who created the land. The wings of Warepil spread to either side of Sirius across less bright stars. The wedge-tailed eagle is an important figure right across Australia. For example, the Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri in the Melbourne area connect the eagle, Bunjil, to the star Altair (which coincidentally is the brightest star in the Greek constellation of Aquila the eagle). Bunjil has two wives in the form of black swans which are the stars Tarazed and Alshain that sit either side of Altair.

Kulkunbulla (Kool-koon-boo-la “oo” as in book)

Kulkunbulla, the two young dancing men, is found in one of the most recognisable constellations, the belt and the sword of Orion. Song and dance were very important to Indigenous Australian cultures, as they were one of the main ways that stories and information were remembered and passed on.

Yurree (Yoo-ree “oo” as in book) & Wanjel (Wan-jel)

Yurree and Wanjel are the two hunters who pursue Purra the kangaroo. Yurree is the fan-tailed cuckoo and Wanjel is the long-necked tortoise. They are a bright pair of stars in the sky known to Europeans as Castor and Pollux, the two twins of Gemini. The appearance of these stars in the night sky indicate seasonal patterns for both of these animals. Yurree & Wanjel reappear in the sky in late spring, when the fan-tailed cuckoo becomes active again. The stars are most prominent in the sky in late summer, when the long-necked tortoise lays its eggs.

Tchingal (Chin-gel)

Tchingal is the evil emu that terrorised people. It was hunted by the brothers Bram, and eventually killed by Weetkurrk. The battle between these helped to create the landscape of western Victoria. Tchingal is seen in the sky as a series of dark nebulae. The head of Tchingal is the Coalsack, the dark nebulae next to the Southern Cross. The neck of Tchingal goes through the two pointer stars and the body extends to the large dark nebulae near Scorpius. Unfortunately, light pollution means that the Milky Way cannot be seen from the city, so you need to go to the dark skies of the country to see Tchingal.

Brolgas

Another Boorong constellation that you need to go to the country to see are the two Brolga’s eggs, or as we call them the Magellanic Clouds. These are visible from dark skies near Melbourne all year round.

Neilloan (Nay-e-lo-en)

Neilloan is the Mallee fowl and is based around Vega, the fifth brightest star in the night sky. Neilloan is far to the north. It appears in the morning sky in autumn, when the mallee fowls start to construct their nest. It disappears from the evening sky in spring, when egg laying season begins. In late April, Neilloan is the source of the Lyrid meteor shower.