The Science of Fishing

The exponential growth of science in the 19th century went hand in hand with rapid expansion of European dominion across the globe. Description of natural resources in Britain's Australian colonies was driven as much by the potential of their commercial exploitation as by scientific curiosity.

In Melbourne, Frederick McCoy sought to lay down the scientific groundwork for commercial enterprises on a number of fronts.

From 1856 onward he was involved with the Geological Survey of Victoria, the education of potential workers in new techniques for extracting gold and the identification of exotic species for the control of agricultural pests, as well as describing native species with commercial potential.

Not satisfied with the natural resources of the colony he was foremost among a group of citizens who wished to improve the human environment by the introduction of selected species distant habitats.

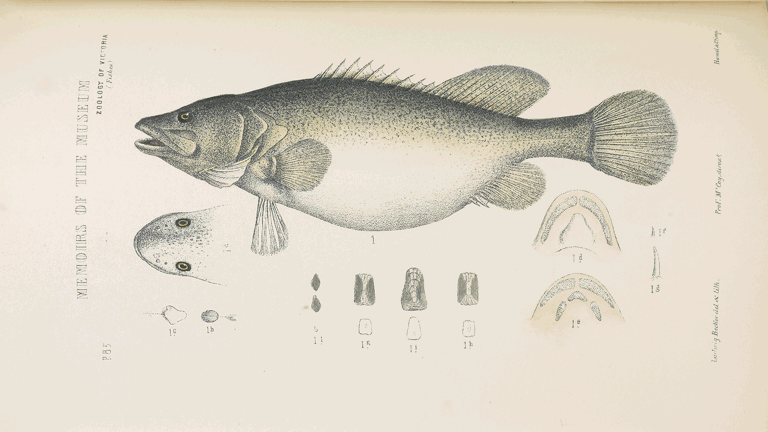

Addressing the first annual lecture of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, McCoy commented on the 'extraordinary fact' that while 'every other similarly situated country on the face of the Earth' had been provided with 'a profusion of individuals of ruminants good for food, not one single creature of the kind inhabits Australia.1' It is therefore not surprising that he described 61 species of fish in his Prodromus of the Zoology of Victoria, many with commercial potential.

McCoy took his role as a taxonomist seriously. The pages of the Prodromus reveal several instances where he assisted in the identification of a fish species from which Melbourne's entrepreneurial gentlemen were hoping to make a killing.

1Linden Gillbank, 'Animal Acclimatisation: McCoy and the Menagerie That Became Melbourne's Zoo', The Victorian Naturalist Volume 118 (6), 2001.