Further stories about the journeys made by Australian immigrants can be found at Melbourne's Immigration Museum and other cultural heritage organisations. A wealth of additional information is available online and in print.

Cultural Heritage Organisations

Immigration Museum

museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum

Old Customs House, 400 Flinders Street, Melbourne, Victoria

Telephone 03 9927 2700 or Education Bookings 03 9927 2754

Exhibitions explore stories of people from all over the world who have migrated to Victoria since the 1830s. Education programs and Immigration Discovery Centre provide resources for all ages.

Migration Museum

migration.history.sa.gov.au

82 Kintore Avenue, Adelaide, South Australia

Telephone 08 8207 7580

Exhibitions focus on immigration history, cultural diversity and settlement in South Australia. Education programs actively promote cultural and ethnic tolerance.

National Museum of Australia

www.nma.gov.au

Lawson Crescent, Acton Peninsula, Canberra, ACT

Telephone 02 6208 5000

Online Resources

Australian Bureau of Statistics

www.abs.gov.au

A range of information and statistics online, including: Migration Australia (series 3412.0), recent Year Books and the Population Clock.

Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI)

www.acmi.net.au

Exhibitions include Transiting Bonegilla short films by women who passed through this post-war Migrant Reception Centre, and an extensive catalogue of films and videos available for loan. These include Mike and Stefani, a documentary-style production released in 1952 to publicise Australia's participation in the international program to re-settle the 'Displaced Persons of Europe' after World War II.

Australian Human Rights Commission

www.humanrights.gov.au

An organisation set up to foster greater understanding and protection of human rights in Australia and to address the human rights concerns of individuals and groups.

Citizenship in Australia: A Guide to Commonwealth Government Records

guides.naa.gov.au/citizenship

Materials held by the National Archive, collected under themes such as nationality and citizenship, naturalisation, the treatment of aliens, assimilation, concepts of racial and national identity. Available in print: 114p, 1999, ISBN 0 642 34408 6, No. 10.

Also More People Imperative: Immigration to Australia, 1901–39

guides.naa.gov.au/more-people-imperative

An overview and guide to records in the National Archives collection on Commonwealth immigration policies from 1901 to 1939, including both those that encouraged and those that restricted immigration. Available in print: 236p, 1999, ISSN 1326 7078, No. 7.

Department of Home Affairs

www.homeaffairs.gov.au

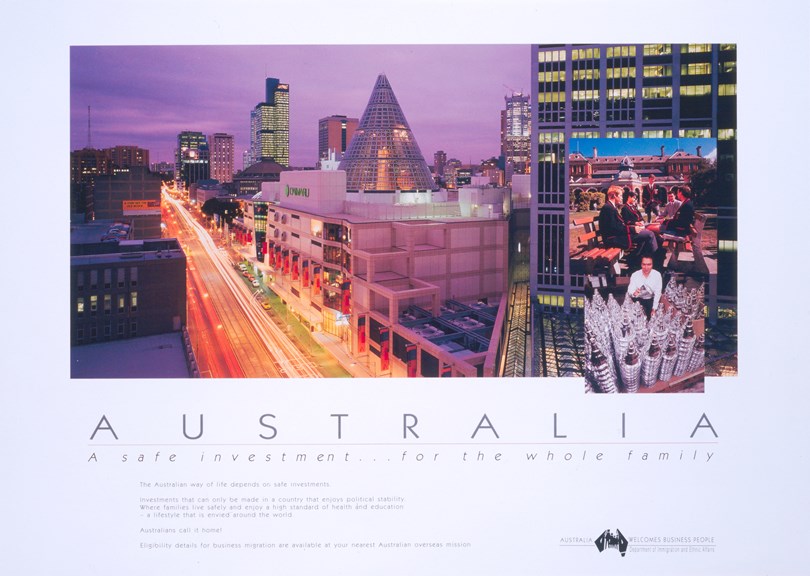

Includes current Australian immigration information: www.australia.gov.au/information-and-services/immigration-and-visas

Documenting a Democracy

www.foundingdocs.gov.au

This Australian National Archives website tells the story of Australia through the documents which give our national, state and territory governments the right to govern. It includes copies of Immigration Acts and related documents grouped by date, State or theme (e.g. Immigration Restriction Act: www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item-sdid-87.html).

Horizons: The peopling of Australia since 1788

www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/horizons/home

Extracts from an ongoing exhibition at the National Museum of Australia about the 10 million people who have migrated to Australia since 1788, where they come from, and how migration has shaped the nation we know today.

Immigration and Nation-Building

www.abc.net.au/federation/fedstory/ep2/ep2_events.htm

Section of the Federation Story project produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation for Australia's centenary of Federation.

The papers of James Günther, 1837–42

www.newcastle.edu.au/centre/wvp/papersofjamesgunther

Vol 3 Transcripts of Letters and Journals sent to the London Corresponding Committee of the Church Missionary Society, 1837-42. Letters 1-3 include first hand accounts of a weather-affected voyage to Australia in 1887.

Monash University Centre for Population and Urban Research

arts.monash.edu.au/cpur

Publications include People and Place, which presents information on migration patterns and related topics (past editions are free to download).

National Archives of Australia

www.naa.gov.au

Extensive records and information services, including Making Australia Home – a service that provides migrants and their descendants with copies of records that document their family's arrival and settlement in Australia: www.naa.gov.au/collection/explore/migration/home.aspx

National Film and Sound Archive (formerly ScreenSound Australia)

www.nfsa.gov.au

An extensive catalogue of films and videos is available online; many can be viewed at NFSA Offices or Access Centres. Education programs are also available, including Voices and Visions based on the film Mike and Stefani (as for ACMI listing above).

Newspapers

The Age

www.theage.com.au

The Australian

www.theaustralian.com.au

The Courier-Mail

www.couriermail.com.au

Mercury

www.themercury.com.au

The Sydney Morning Herald

www.smh.com.au

The West Australian

thewest.com.au

Origins: Immigrant Communities in Victoria

museumvictoria.com.au/origins

An overview based on census data 1854–2006, with the immigration histories of 70 communities presented in English and community languages.

Parliament of Australia

www.aph.gov.au

Includes current parliamentary committee reports on migration, related issues such as detention centres, Hansards and much more, including historical information.

Refugee Review Tribunal

www.rrt.gov.au

Database of published reports, together with information about the tribunal and its functions; includes a review of decisions made by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (previously Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs - DIMA).

State Library of Victoria

www.slv.vic.gov.au

A wide range of catalogues and databases online, providing access to digital images of Manuscripts and Pictures (photographs, prints and drawings).

See also:

National Library of Australia

www.nla.gov.au

Northern Territory Library

ntl.nt.gov.au

State Library of New South Wales

www.sl.nsw.gov.au

State Library of Queensland

www.slq.qld.gov.au

State Library of South Australia

www.slsa.sa.gov.au

Libraries Tasmania

libraries.tas.gov.au

State Library of Western Australia

slwa.wa.gov.au

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR)

www.unhcr.org

Up-to-date news, facts and statistics about refugees world-wide.

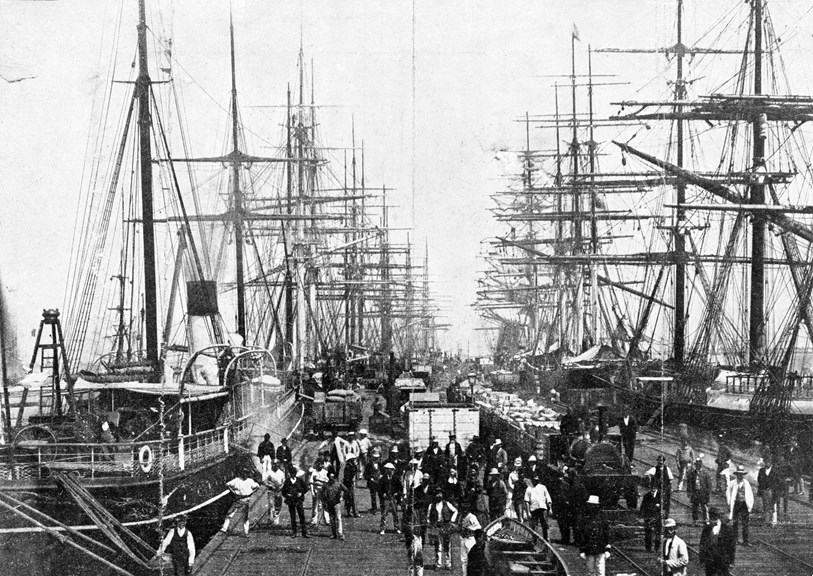

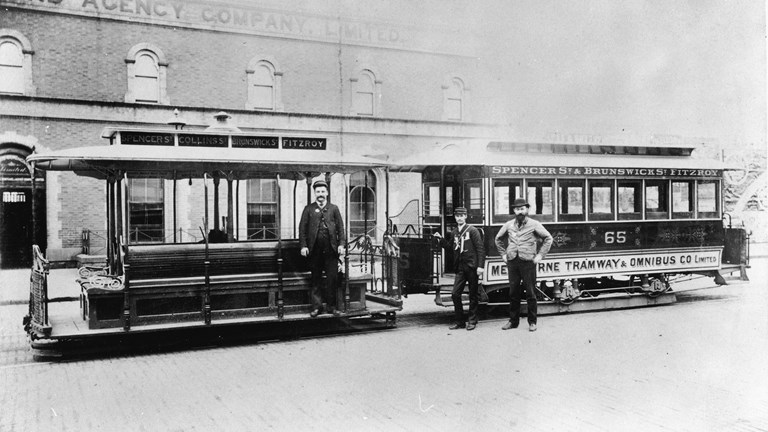

Victorian Railways

museumsvictoria.com.au/railways

Includes a database of photographs with historic images of Sandridge, Railway and Station Piers.

Resources in Print

Coffey, B R (ed), Sunburnt Country: Stories of Australian Life, Fremantle Arts Press; ISBN 186368364X

A selection of autobiographical stories and short fiction about Australia and Australians of all ages, including some who made the journey to Australia.

Cole-Adams, J and Gauld, J, Australia's Changing Voice, Rigby Heinemann, 2003; ISBN 0 73123 430 8

Before European settlement, over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages were spoken in Australia. Although many of these languages are extinct, a similar number of other languages from around the world are spoken here today. Includes examples of Australian colloquial language from various decades. Also: Our Voices multimedia series for primary students, exploring historical and contemporary issues in Australian life.

Lewis, Robert, Destination Australia: the Migrant Story Study guide, ScreenSound Australia, National Screen and Sound Archive. (Now National Film and Sound Archive)

The story of immigration to Australia – from 1901, when the Immigration Restriction Act was created with Federation, until the late 1970s and 'multiculturalism'.

Gleiztman, Morris. Boy Overboard, Puffin Australia 2002; ISBN 0141308389

Jamal and Bibi have a dream – to lead Australia to soccer glory in the next World Cup. But first they have to face landmines, pirates and storms as the family embarks on a journey, from Afghanistan.

Also: Girl Underground, Puffin Australia 2004; ISBN 0143300466

Bridget wants a quiet life, then a boy called Menzies makes her an offer she can't refuse – a daring plan to rescue two kids, Jamal and Bibi, from a desert detention centre.

Pung, Alice. Unpolished Gem, Black Ink Australia 2006; ISBN 186395158X

The arrival of the author's Cambodian-Chinese family in Melbourne in the 1970s, growing up in Footscray between two cultures, and the constant battle of balancing parents' expectations with one's own.