Why the 2010s were the decade of the peacock spider

How digital technology transformed an invertebrate into an influencer—and led to a frenzy of scientific discovery.

He’s not yet graduated university, but Joseph Schubert has already scientifically described five species of spiders, capturing international headlines.

And the Museums Victoria legacy registration officer is set to describe at least another five in early 2020.

The reason such a young researcher could make such a splash is because of the type of spiders in which he specialises. Spiders which catapulted into stardom in the 2010s.

Until 2011 there were seven named species of Maratus spiders.

The spiders are found in backyards across Australia but, at that point, they were far from household names.

To the naked eye, Maratus are often brownish, hopping specks. For most people, they were simply another among the indistinguishable horde of things that crawl, wriggle and bite their way through the muck of Earth.

Transcendental things happen to a Maratus spider, however, when it is placed under a microscope—or a macro lens.

First, its true colours are revealed. Violets, jades, vermilions—iridescent clouds that swirl into psychedelic patterns on some species and form shapes likened to elephant heads, arrows or skeletons on others.

Second, the spider’s seemingly sporadic jerks are revealed as an elaborate dance. One that combines the flair of fandango with the speed and spring of a Marvel superhero.

On this stage, it can be appreciated for what it is: literally, a dance of life and death. If the swaggering male fails to seduce his would-be lover, she may well eat him.

It is under a microscope that this story is revealed—and the species’ common name makes sense.

On this scale, our humble Maratus is transformed into a peacock spider. It also takes on characteristics rarely associated with arachnids. Its exaggerated movements become funny—adorable even.

But good luck telling folk that a spider is cute.

Until 2011, anyone who thought a peacock spider was adorable was probably Australian and almost certainly an arachnologist.

Two digital developments of the 2000s plucked the peacock spider from obscurity.

First, cameras that could capture the spiders’ colour and movement on video. Second, social media—and its insatiable appetite for cute animals.

A YouTube video of the coastal peacock spider’s courtship dance has clocked more than 7.9 million views. Others see peacock spiders dance to the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive, wearing photoshopped sombreros and playing maracas or with titles like Spider Dances For His Life!!!.

By 2019, the peacock spider had become a social media influencer of the invertebrate world.

Gallery

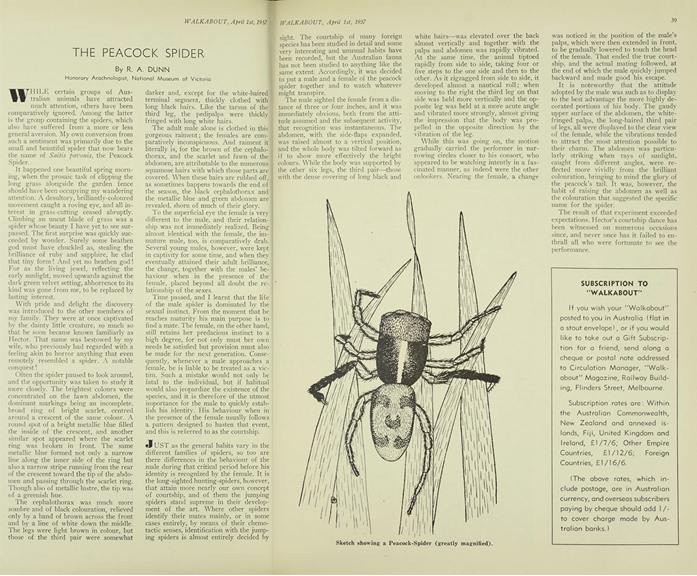

In April 1957, R. A. Dunn, an arachnologist with what is now Museums Victoria, published 'The Peacock Spider' in a precursor of Australian Geographic.

In a charming and accessible piece of prose, Dunn describes how—a decade earlier—he had discovered a spider ‘clothed in a gorgeous raiment’ in his backyard while performing the ‘prosaic task of clipping the long grass’.

Dunn took the ‘living jewel’ into his home and began studying it. He named the species pavonis, Latin for peacock. His family named the spider Hector.

After observing that ‘the life of the male spider [was] dominated by the sexual instinct’, Dunn began capturing females too and closely observing their interaction.

Not only did Dunn record the result, he shared it with others.

‘Hector’s courtship dance has been witnessed on numerous occasions since, and never once has it failed to enthrall all who were fortunate to see the performance,’ he wrote.

But though Dunn’s neighbours and family might have been captivated by the spectacle, his written account and black-and-white sketch were not enough to excite the public at large. His piece ran on page 38 and 39 of Walkabout.

Jürgen agrees that things might have turned out differently, had Dunn ‘the technology of today’.

‘I imagine he would have produced a YouTube video and that would have kicked things off in the same way as what happened when I put my photographs and videos online,’ he says.

It’s not just scientists, of course, who have access to that transformational technology.

Jürgen’s videos have helped inspire a small legion of citizen scientists and amateur photographers. It hasn’t reached the scale of twitching, but the burgeoning community of peacock spider hunters are every bit as besotted with their ‘mini birds of paradise’.

Obsession and a camera, however, don’t—in and of themselves—lead to the formal discovery of new species.

Citizen scientists frequently find undescribed species in the wild, but they then require a trained scientist to classify and name it in the lab.

This was the case for the first peacock spider Jürgen described: Maratus harrisi, named for Stuart Harris who was, at the time, a Canberra-based garbage collector—a story told in the documentary Maratus.

Jürgen’s relentless drive and unorthodox publishing arrangement allowed him to churn out new species descriptions at breakneck speed. But despite the global attention peacock spiders were receiving, despite the influx of people suddenly looking them, photographing and videoing Maratus, there were remarkably few new scientists describing the resultant species’ boom.

In fact, there was only one: a Melbourne undergraduate biologist and reformed arachnophobe called Joseph Schubert.

At 22 years of age, Joseph has already named five species of peacock spiders and landed a job at Museums Victoria.

He is currently working on several more undescribed species, and is hoping to have at least five published and then officially named in early 2020.

In the world of the peacock spider, Joseph inhabits rarified air. Despite all the hype and frenzy, in the boom years from 2011 there have been only four sources of new names. Otto & Hill with their 47 species. Julianne Waldock, with her total of nine. Queensland Museum arachnologist Barbara Baehr and her collaborator Robert Whyte (6). And Joseph.

As a teenager, Joseph kept spiders as pets to overcome his phobia. Fear turned to fascination, leading him to a Facebook post that introduced him to peacock spiders. He decided to see if he could find one in the wild.

‘They are honestly everywhere.’Joseph Schubert

‘You go twenty minutes from the museum, you’ll find a tasmanicus. If you’re ever at the beach keep an eye out on the pigface.’

Joseph not only has a talent for finding Maratus, he has the skill to scientifically describe them. In the latter, he has been mentored by the aforementioned Barbara Baehr. Joseph described his first peacock spider in the Brisbane home Barbara shares with her partner Robert Raven, himself senior curator and arachnologist at the Queensland Museum.

Barbara has described more than 600 species and written the book on Australian spiders, literally. Joseph has a treasured signed copy of A Guide to The Spiders of Australia, of which she is co-author.

‘For Joseph, the most enthusiastic spider person I know,’ it reads.

The pair have even struck an unlikely friendship.

When I met them on a field trip in Victoria’s Little Desert, Barbara told me of a childhood spent searching for salamanders and May beetles in the Germany’s Black Forest, of the quiet enchantment she discovered in the Queensland outback with her first husband.

Joseph sleeps through his alarm on first day of the trip, emerging with the field biologist’s khaki uniform complimented by a Nike cap turned backwards, a bar through his left ear a peacock spider tattoo on his arm.

The pair spend two weeks on hands and knees, beating bushes and sweeping nets, placing their live quarry in plastic vials they keep safely stored in bumbags slung around their waists. At the end of long, hot days, they spend the evenings identifying and documenting their finds. Joseph is up late, camera whirring as he tries to capture his tiny, jumping quarry.

Like Jürgen, Joseph is driven, a keen photographer, trained scientist and active on social media.

Here is Maratus occasus, a brand new peacock spider I described from Queensland, Australia. The species name 'occasus' translates to sunset, a reference to the colours of the male. This species was discovered in 2017 by Philip Price. Thanks to Michael Duncan for the first photo! pic.twitter.com/YKmy831oFm

— Joseph Schubert (@j_schubert__) June 29, 2019

But whereas Jürgen believes the peacock spider discovery boom has mostly run its course, Joseph hopes more may yet be found. As with most scientists, he is loath to speculate, but says he wouldn’t be surprised if turned out there were ‘upwards of 100 species’ of peacock spiders.

For her part, Barbara is fairly blasé about peacock spiders. She’s pleased they capture people’s imagination and happily agrees they are cute. But when it comes to serious research, her taste is more inclined towards, say, Zodariidae—a family of mainly small, brown, ant-eating arachnids.

Unlike the general public, the interests of biological experts are rarely confined to the showy and the charismatic of the natural world.

I’ve walked through fields of orchids and wildflowers with botanists who only had eyes for moss. So while it makes sense the wider world didn't care about peacock spiders until it was captivated with their colour and movement, why weren’t more arachnologists looking for Maratus—before they were cool?

Jürgen has a hunch. He says funding for biological research in Australia is generally targeted at species which are either dangerous to humans or harmful to agriculture.

Which is one reason why more is known about, say, mites than is about peacock spiders.

The Australian National Insect Collection and its CSIRO’s entomology department back onto Canberra’s Black Mountain. As a result, its invertebrate fauna is probably the most thoroughly surveyed in Australia, Jürgen says.

And yet it took Stuart Harris, the one-time garbage collector of Maratus harrisi fame, to discover a new species, Maratus calcitrans, living in that very patch of bush.

His life transformed by peacock spiders, Stuart has found at least four species, all of which have been described by Otto & Hill.

With so little known about peacock spiders, all the researchers I spoke to for these piece spoke about the need for this kind of collaboration. To that end, Barbara has named one peacock spider species after Julianne and another after Jürgen. But now that there is fame, if not quite fortune, to be found in the study of peacock spiders, there is also—inevitably—competition.

‘You could say it’s the Wild West,’ Barbara says with a wry smile.

‘Only, until now, there is no shooting.’

Though no physical shots have been fired, even the quaint world of peacock spiders is not immune from the dark side of the internet.

Social media might have been the secret to the meteoric rise of Jürgen ‘and his dancing spiders’—as the Sydney Morning Herald put it—but these days, he’s trying to kick the habit.

He’s tired, he says, of the negativity it engenders and the time it absorbs.

Instead, he’s focusing on a new hobby: learning Arabic, travelling to Jordan and Palestine. Though peacock spiders now play ‘second fiddle’ in Jürgen’s life, they are, still, indelibly with him. There’s the constant whooshing in his ear—tinnitus he says, caused by the stress of juggling full-time work with his peacock spider crusade. And then there’s the pang of fear he feels when he sees certain patches of forest burn.

When fire rips through an area, peacock spiders are likely to be wiped out, and unlikely to recolonise effectively, he says.

In only the first month of summer, 2019/20 has already been a catastrophic fire season across the eastern seaboard. And the scientific consensus is that climate change will make such fire seasons more frequent.

Which could be devastating for some peacock spiders, given how geographically confined many species appear to be.

Maratus sarahae, for example, is known to inhabit just two peaks in WA’s Stirling Ranges. One of which, Bluff Knoll, was engulfed in flames in 2018.

The case to better conserve these enigmatic spiders is enhanced by the distinct possibility that we are now discovering just a fraction of their diversity prior to European colonisation.

‘I suspect that Australia's peacock spider fauna was actually much richer than it is today and that we are just seeing a remnant of it.’Jürgen Otto

This is based on the fact that peacock spider hotspots like south-west WA and south-eastern Australia often coincide with areas of intense agriculture or urbanisation.

Of course, we are unlikely ever to prove or disprove that suspicion, but there is so much about peacock spiders still to be discovered. How many species remain? What is their range? How long does it take for them to bounce back from fire?

These questions are just the tip of the iceberg, and mean the future for Maratus may rest in the hands of researchers who can answer them and the passionate citizen scientists who often enable them.

For the rest of us, perhaps we can play a role by maintaining a sense of awe in what R. A. Dunn described, all those years ago, as a spider of unsurpassed beauty.

Perhaps we too can wonder, and surmise:

‘Surely some heathen god must have chuckled as, stealing the brilliance of ruby and sapphire, he clad that tiny form!’R.A. Dunn

Written by Joe Hinchliffe, Museums Victoria