The trials and triumphs of a trailblazing scientist

Hope broke down barriers and inspired generations of Australian scientists—but it came at a cost.

Hope Macpherson was a woman used to breaking barriers.

In 1937, her initial scientific ambition thwarted due to the ‘inappropriateness’ of a woman being a taxidermist, she became a museum assistant and specialised in malacology.

By 1946 she had been appointed curator of molluscs, becoming the first woman to take on the more senior curatorial role at what is now Museums Victoria. She described new species of sea snails and worms and co-wrote the first field guide to molluscs in Victoria.

In an era where women were expected to run households, Hope ran off on expeditions.

She surveyed the Snowy River Gorge on pack horses in the 1940s and, in 1959, Hope was a member of the first group of women to travel to the Antarctic on an Australian research expedition.

Then, at the height of a trailblazing scientific career, Hope was compelled into a most stark and cruel choice: continue her life’s work and career’s upward trajectory—or start a family.

It is a choice many women still face. But, in Hope’s case, it was enforced by both law and religion.

The year was 1965 and Hope was in love with a meteorologist, the widower Ian Black. She was 46-years-old.

This time, the barrier Hope faced was not social nor unwritten.

This was the era of the Marriage Bar, which prevented married women from working in the public sector.

While some woman chose to keep their marriage secret, Hope’s faith and commitment to family ruled out that option. Hope chose love.

MV history of collections and scientific art senior curator Rebecca Carland interviewed Hope before she died in 2018 and collected her photographs, letters and personal items.

Bec says marriage opened a rich new chapter in Hope's story. She retrained as a teacher and went on to inspire generations of young women to pursue science. She moved to a farm, had a daughter and a ‘wonderful life’ with Ian.

But fate had a cruel sting left in store for her. In 1966, the Marriage Bar was rescinded. It came months too late for Hope.

Hope ‘never expressed dissatisfaction’ her lot, Bec says. Similarly, the idea of being an ‘extraordinary character was anathema to her’.

‘Hope was a very stoic character,’ Bec says.

‘She was complex ... gloriously complex.’

Despite standing down from an official leadership role, Hope continued her association with the museum for the rest of her life, volunteering as a researcher, going on field trips. For another six decades, she would mentor many scientists, female and male.

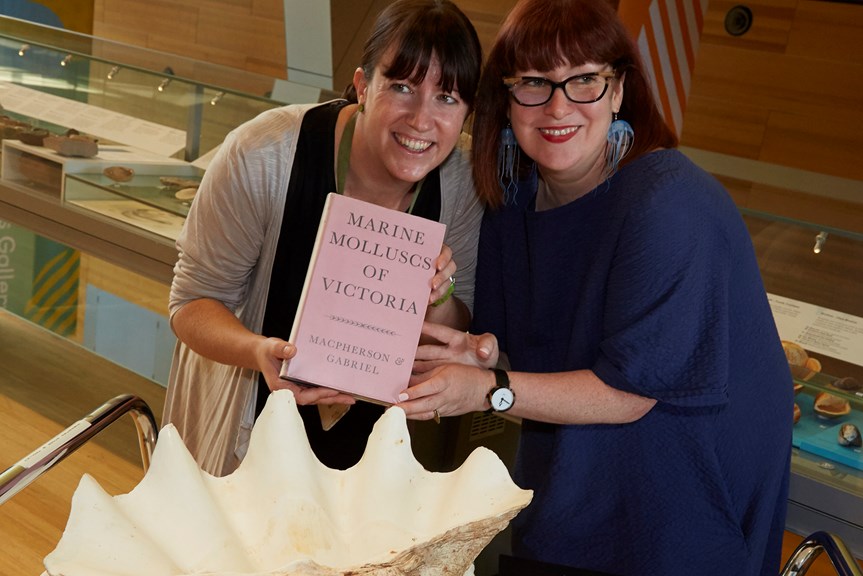

MV marine invertebrates collection manager Melanie MacKenzie is one of the current crop of museum scientists to whom Hope remains an inspiration. Mel has a treasured signed copy of Hope’s field guide.

‘She was a trailblazer, someone who proved that women can achieve in science and discover new things and go out and explore,’ Mel says.

Both Hope's legacies of Antarctic exploration and species discovery live on in Mel's research.

In 2012, Mel was part of a British expedition surveying the floor of the Weddell Sea, a voyage which yielded creatures of the deep, many of which had never been seen before.

Hope's own scientific legacy lives on too. The data from biological surveys of Port Phillip Bay from 1957-1963, of which Hope’s was a major part, is used to this day as a benchmark against which to monitor environmental changes.

Yet MV senior manager of genetic resources Dr Joanna Sumner can’t help but wonder what Hope might have achieved had she continued in her curatorial role.

‘The scientific world missed out on half of her professional life,’ Jo says.

‘I don't know that anybody has ever stepped into her shoes.’

While the museum may still be waiting for another with Hope's specific expertise, there are 33 women among its scientists today, alongside 37 men.

However there remains a disparity in the number of curators: 12 male to four female.

MV archivist Nik McGrath says though Hope’s story is better documented than many, hers was far from an isolated case.

Unlike their male counterparts, these women rarely had biographies written about them. Many married, changed their names and professions.

Despite their trials, they too experienced triumph. Women like chemist Anne Bermingham, who set up Australia’s first radio carbon dating lab in 1961. Mineralogist Sylvia Whincup, invertebrate paleontologist Joyce Richardson. The list goes on.

‘There are a lot of hidden women in the archives,’ Nik says.

‘Hope opened doors for them.’

Nik has been poring through the museum records trying to flesh out the stories of other pioneering women in science.

‘It’s not surprising that there is a gender bias in Wikipedia and Australian Dictionary of Biography,’ she says.

‘But it is something that historians and researchers need to do something about.’