The surprisingly Australian history of Chinese dragon parades

Sophie Couchman, Museums Victoria Research Institute and Leigh McKinnon, Monash University

Tomorrow will usher in the lunar Year of the Dragon. Families and friends will gather to feast, red packets will be gifted to youngsters, and dancing Chinese lions accompanied by strings of crackers will scare away evil spirits and bring good fortune to businesses.

In celebration of the new year, much-loved Chinese dragons will parade on Australia’s streets, including Sun Loong in Bendigo and the Millennium Dragon in Melbourne.

While dragon parades are popularly viewed as displays of Chinese or Cantonese tradition and culture, their history demonstrates how deeply Australian they also are.

Our historical research shows that until relatively recently Australia’s dragon parade tradition was closely associated with Chinese-Australian philanthropy and engagement with Australian civic life, rather than with Chinese spiritual practice.

The earliest dragon arrivals

Australia’s Cantonese immigrants and their descendants have long used dragon processions as ostentatious displays of their culture. Some of the organisers of dragon parades have ancestry dating back to the 19th-century gold rushes. The history of these dragons is almost as old.

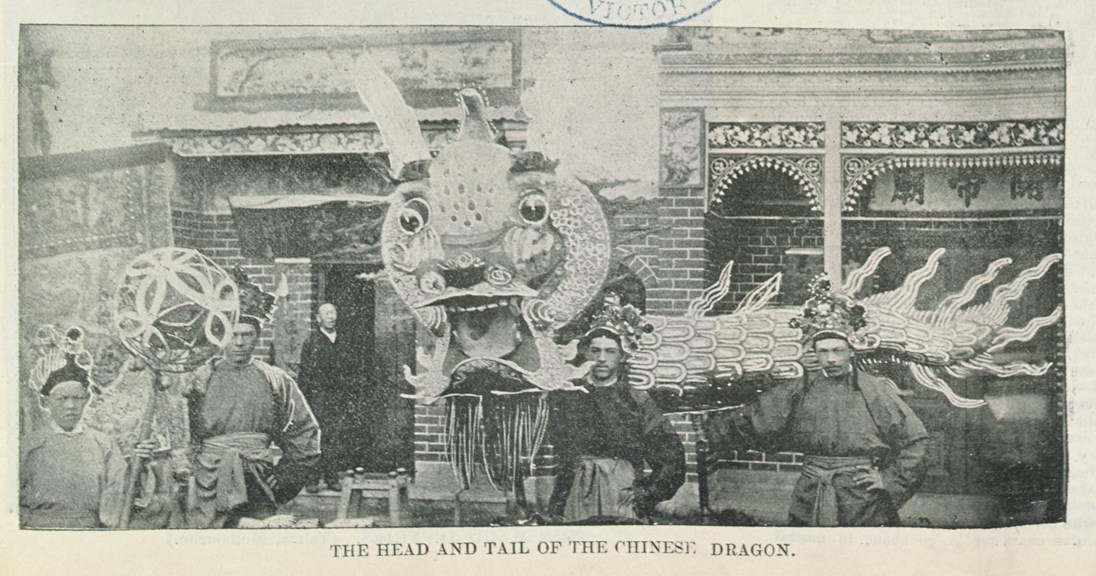

The first dragon, nicknamed the “Duck Bill” dragon, was imported from Southern China to Bendigo more than 100 years ago and paraded from 1892 to 1898.

Nearby, Ballarat’s first dragon – also the oldest surviving dragon – was purchased in 1897. It was paraded until the 1960s. Ballarat’s dragon is held at Sovereign Hill.

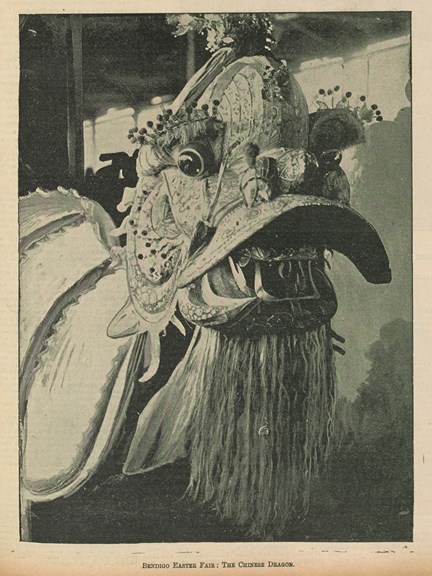

The “Moon Face” dragon was Bendigo’s second dragon, paraded for just one year in 1900. Then, in 1901, Bendigo imported its third dragon, “Loong”. Remarkably, Loong was paraded for more than 100 years (circa 1901-2019) and now resides at the Golden Dragon Museum.

Melbourne also got its first dragon in 1901, which was paraded until about 1915. It’s now held at the See Yup Temple in South Melbourne.

Bendigo’s Chinese communities, their descendants and friends maintained a continuous dragon parading tradition. Ballarat and Melbourne’s fell away – only to be revived in 1954 to mark the visit of Queen Elizabeth II.

Meanwhile in southern China, where these parades originated, the tradition almost died out after the Cultural Revolution.

A valued part of local fundraising

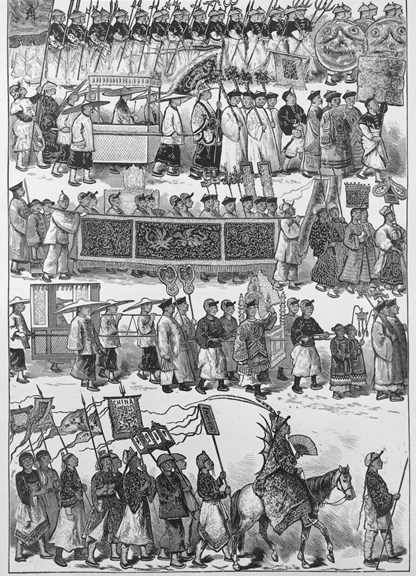

Australian streets have provided a stage for a variety of processions, with public holidays used to stage open-air fundraising activities (particularly for hospitals). Chinese communities were as keen as everyone else to assist with fundraising, display their culture and participate in festivities.

Historian Pauline Rule has shown that Chinese communities have contributed to public fundraising displays in rural cities since at least 1866.

Bendigo’s Chinese community has helped raise funds for the Bendigo Hospital at its annual Easter fair since 1879. In 1884, the organising committee of Castlemaine’s charity parade specifically sought the involvement of the local Chinese community.

The popularity of dragons

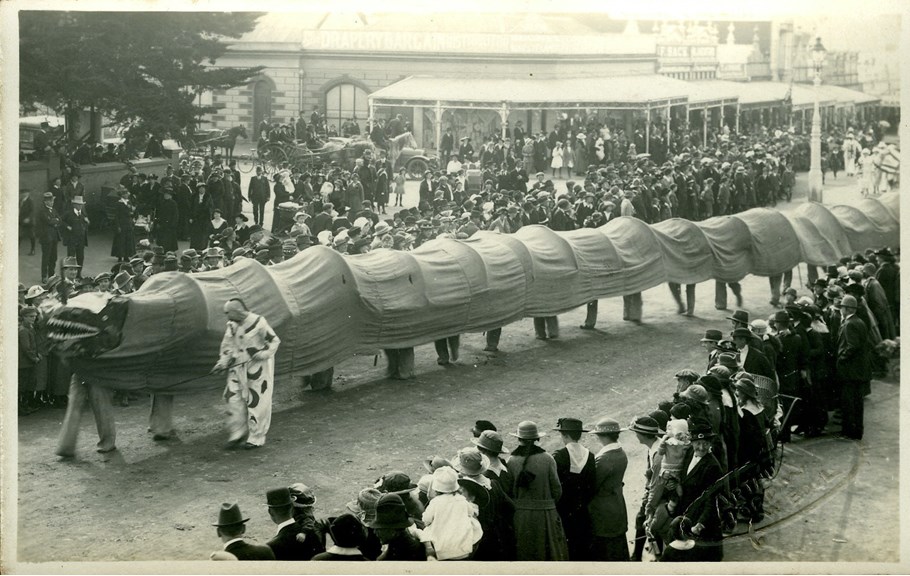

Dragons were expensive and valued, and as such were also loaned to other communities for fundraising displays. In 1897, Bendigo’s Duck Bill dragon travelled to Sydney to participate in the Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee fundraiser. Then, both Bendigo’s Moon Face and the Ballarat dragon, as well as costumes from Bendigo, Beechworth and Castlemaine, were loaned to raise funds for the Melbourne Women’s Hospital in May 1900.

That so many Victorian communities could purchase dragons demonstrated their prosperity and joint commitment to Australia philanthropy and public life. It perhaps also encouraged a friendly intercity rivalry.

Processional dragons were so popular that some communities that couldn’t access one would make their own imitation ones.

Royal welcome

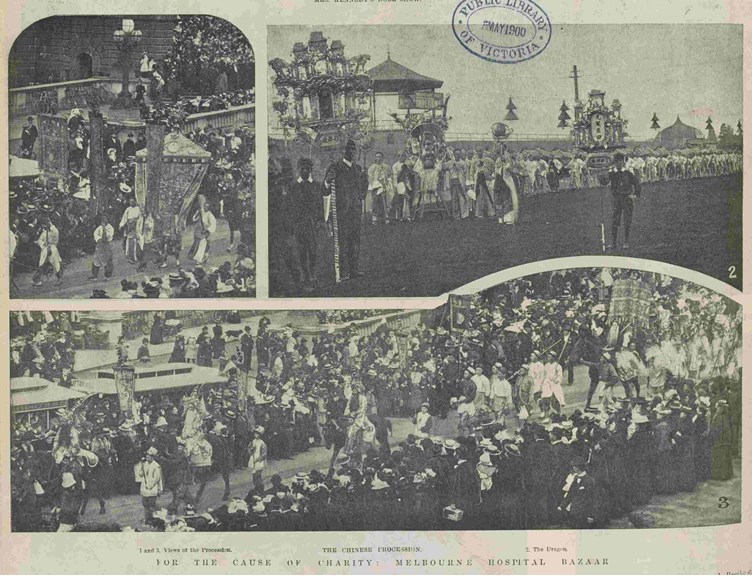

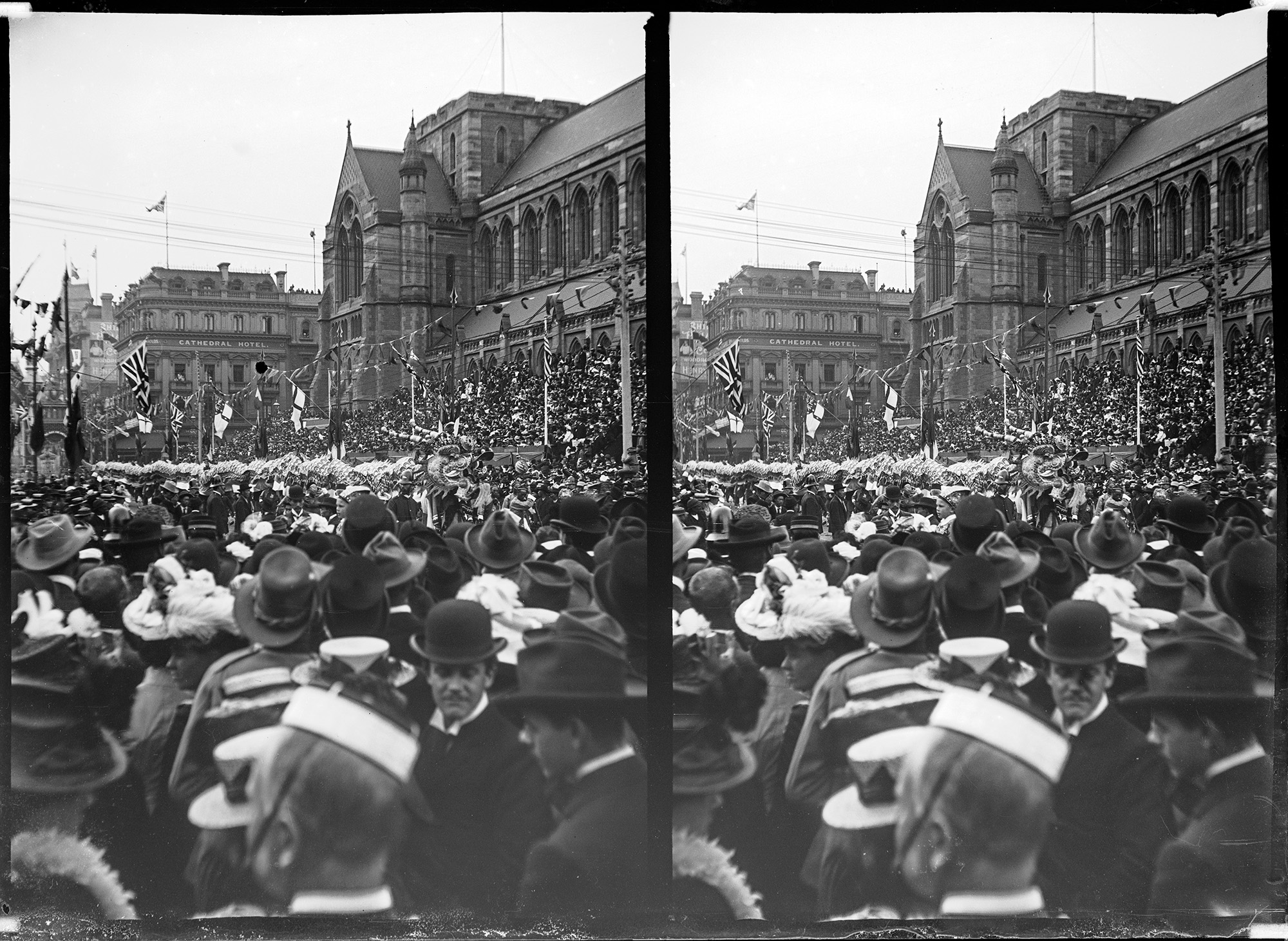

By the time the Duke and Duchess of York arrived in Melbourne to open the first federal parliament on May 6 1901, Chinese participation in public processions in Victoria was common. Of the five Chinese dragons brought to Victoria in the 19th century, three participated in Federation celebrations.

As John Fitzgerald shows, many Chinese Australians were as excited about the possibilities of Federation as other Australians. They “shared a grand vision of what Australia might become in the century ahead”. To mark the royal visit, welcome arches were constructed in Melbourne, Ballarat and Perth.

Thanks to early photography, we can identify the two dragons that paraded in Melbourne. Several photographs show Bendigo’s Loong was one of these.

Only a few long-distance photographs of the other dragon survive.

They show that, while the dragon’s beard is positioned differently and some decorations are missing, the striped horns and head match the Melbourne dragon held at the See Yup Temple in South Melbourne. According to a 1903 newspaper article, Melbourne’s Chinese Bo Leong Society had specifically purchased this dragon for the 1901 celebrations, at a cost of 250 pounds.

The third dragon involved in the festivities, the Ballarat dragon, was used to decorate the Chinese arch that welcomed the royal couple during their visit to Ballarat.

A legacy in Australia

Astoundingly, these three Federation-era dragons – three of the five oldest surviving imperial dragons in the world – still survive today.

Traditionally, when dragons reach the end of their life they are ritually burned. That these dragons were not is another expression of their Australianness. For immigrant Chinese communities, they have acquired special value as examples of cultural practices of distant homelands. Their cultural difference and beauty also appeal to others.

Each dragon is significant in its own right, but together they are remnants of a significant history of Chinese Australians’ participation in local fundraising and celebration.![]()

Sophie Couchman, Honorary Research Fellow, Museums Victoria Research Institute and Leigh McKinnon, Research Affiliate, School of Philosophical, Historical, and International Studies, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.