The electric vehicle future was promised decades ago, what happened?

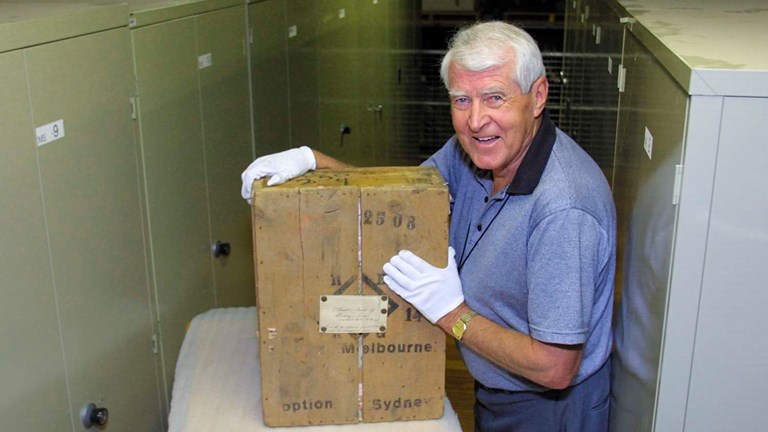

Within Museum Victoria’s collections are thousands of examples of technology that have faded into obscurity, but the electric vehicle is one whose time has come again.

An electric vehicle promising relief from high petrol prices sounds all too familiar these days—but what about 40 years ago?

That reality was closer than you might think.

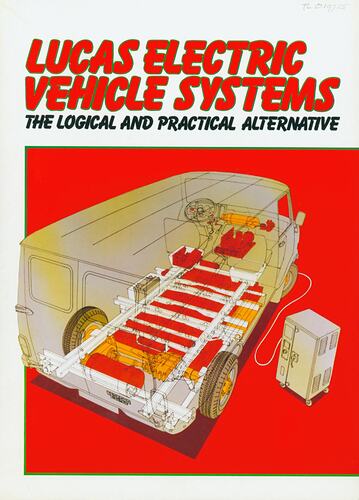

In the late 1970s, one of the companies at the forefront of the technology, British-based Lucas Industries, had begun developing commercial electric vehicles (EVs).

It promised: ‘by the mid-1980s, these high-performance electric commercial vehicles will cost less to own and operate than conventionally powered vans.’

One of these vehicles—a converted Bedford van—resides in the Museums Victoria collection, along with the company’s advertisements about its vision for the future.

‘It demonstrated the practicalities of converting a conventional commercial vehicle to fully electric operation,’ says Matthew Churchward, Museums Victoria’s senior curator of engineering and transport.

‘It proved that it wasn’t that bigger step.’

So, why did it take another four decades for electric vehicles to be widely accepted?

To answer that, we must go back even further.

The electric vehicle revolution...of the 1800s

Automobiles of the 1800s looked more like the horse-drawn carriages they replaced (minus the horses of course) than the cars we know today.

But it was not a foregone conclusion that they would be powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE).

Steam-powered (external combustion) vehicles had been around for more than 100 years by the time Karl Benz’s built his first Motorwagen in 1885, which is widely regarded as the first practical automobile.

And between these two titans of technology, the first electric vehicles began to turn their wheels.

The first prototypes appeared in the 1830s and were closely followed by full-sized wagons.

The invention of rechargeable lead-acid batteries by French physicist Gaston Planté in 1859 only improved their prospects.

Batteries proved useful in all sorts of endeavours that needed backup power, especially in the early days of electrification.

Around the turn of the century usable electric cars were well into production, including the German-made Flocken Electrowagen.

Household names like Ferdinand Porsche, Henry Ford, and Thomas Edison also tried their hands at the technology.

In the early 1900s, more than a third of cars on the road ran on batteries.

By contrast, only about one in five cars sold were powered by an ICE.

Part of the reason for this was that people had to start the engine with a hand crank—something that could (and often did) result in broken bones if the engine backfired.

Electric cars were seen as cleaner and easier to get going, which resulted in them being marketed almost exclusively to women.

But EVs also had issues.

‘Partly it was the weight, the limited range, and the cost of the lead-acid batteries,’ says Matthew.

‘Probably those three factors spelled the death knell of electric vehicles in the 20th century.’

The lead-acid batteries used to power them were heavy and took a long time to charge.

To counter this, several companies introduced battery-swapping stations but, fundamentally, electric cars were slower than their petrol-powered competition and couldn’t travel as far.

Ironically one of the things that most helped to establish the ICE’s dominance over electric cars was an electric motor, as the starter motor eliminated the need for a dangerous hand crank.

Henry Ford’s mass production of cheaper petrol-powered cars, like the Model T, also made electric cars much more expensive by comparison.

While fuel shortages during World War I encouraged the use of EVs, it was short-lived.

‘After the First World War, they ramped up production of petroleum-based liquid fuels and made it more convenient and cheaper,’ explains Matthew.

‘The whole concept of refuelling your car becomes a five-minute job, as opposed to waiting several hours for your batteries to charge.

‘The whole transport economy became structured around the automobile.’

The result was that electric vehicles faded into obscurity in the following decades.

In Australia EVs never really found a foothold with manufacturers or drivers in these early years.

The first car ever built in Australia was a steam-powered car made by Herbert Thomson in 1898.

It was another 50 years before the country saw its first locally designed and mass-produced motor car in the shape of a petrol-powered Holden 48-215.

With cheap petrol Australians and Americans alike grew a fondness for big, powerful cars that used a lot of fuel.

Until access to that fuel became an issue.

Oil crisis: a golden electric vehicle opportunity?

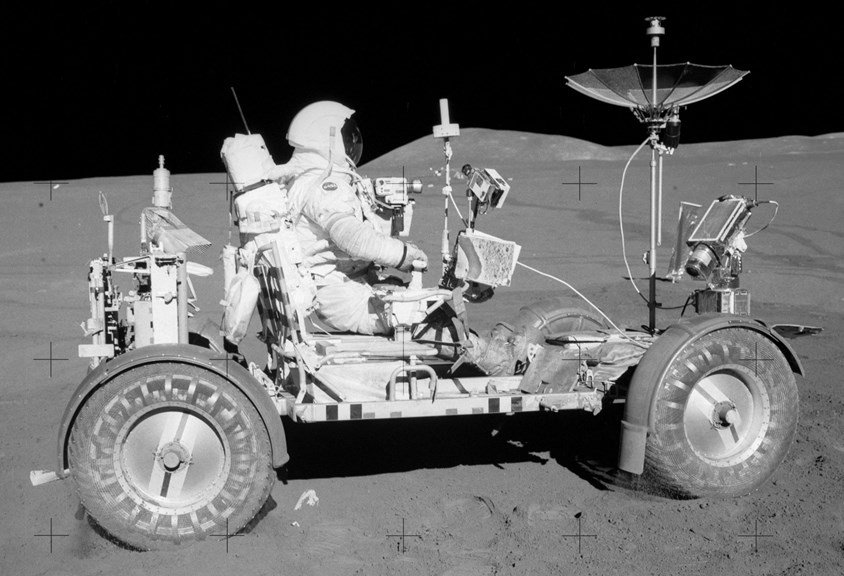

While electric vehicles may have struggled to gain traction on Earth through most of the 1900s, they really took off for extra-terrestrial travellers.

Built by Boeing for Apollo 15 in 1971, the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) allowed astronauts to get around on the surface of the moon.

Granted, LRVs only had a top speed of about 13 kilometres per hour, a range of 92 kilometres, and their silver-oxide batteries couldn’t be recharged.

The first one also cost US$38m to produce and they had to leave it behind.

Back on Earth, a few car companies dipped their toes back into the electrified pool but without much commercial success.

In 1973 the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cut off oil supplies to the USA, in protest for its support for Israel in the Yom Kippur war.

The resulting surge in oil prices caused fuel shortages and rationing in some parts of the world.

‘For the first time in decades people were starting to think about the cost of petrol and environmental factors,’ says Matthew.

It forced manufacturers to consider smaller, more fuel-efficient cars.

But it also presented an opportunity for electric vehicles, which is where the Lucas Bedford fits in.

‘It really was a response to the oil crisis,’ says Matthew.

Lucas targeted the commercial vehicle market, considering it ‘the greatest immediate potential for EV development’.

It started converting vans in 1973 and eventually built about 200 that were sent around the world.

One was even used by Prince Philip in London.

Four of these electric vehicles made it to Australia, where they were trialled on public roads and used in major events like the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games.

It featured energy-saving features like regenerative braking, and a swappable battery pack.

Delivery drivers reported that the electric van was ‘very good to drive,’ and ‘accelerates well’.

While the drivers liked the regenerative braking, they also said it was ‘noisy’.

However, even with Lucas’ developments, the problems of earlier electric vehicles remained.

‘Compared to a petrol-powered van, the electric was more expensive,’ says Matthew.

Its range was also only 100 kilometres and top speed about 80 km/h.

‘With the limited range, commuting or delivery vehicles were the only real practical uses or electric vehicles at the time,’ says Matthew.

But that would all change.

Ionic charge

The answer to the electric car’s biggest weaknesses came in the form of lithium-ion batteries.

It is difficult to overstate how important these small, lightweight, energy dense cells have been to modern technological development—and not just in transport.

Chances are you have one in your hand or pocket right now.

So significant is the lithium-ion battery to modern civilisation that its inventors won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2019.

It was developed over several decades by Michael Whittingham, John Goodenough, and Akira Yoshino and first released commercially by Sony in 1991.

But it took another 17 years to make it into a car.

‘It was a case of waiting for other applications, like laptops and mobile phones, to develop the technology to the point where it could be used in cars,’ explains Matthew.

‘You need that insatiable demand to drive the technological change and development.’

As dire warnings of climate change multiplied, car manufacturers catered to an increasingly environment-conscious market with the introduction of mass-produced hybrid cars.

Hybrids have both a petrol and an electric motor, to reduce emissions and increase fuel economy.

The first was the Toyota Prius, launched around the world in 2000, but it still used the older battery technology.

Tesla became the first to use the newer lithium-ion cells in a production car in 2008—setting the benchmark for the decades to follow.

‘Lithium-ion batteries really tackle the big issues with electric vehicles—the weight and the range,’ says Matthew.

They can also recharge quickly, made all the easier by extensive networks of fast-charging infrastructure.

And the balance has shifted in costs too.

‘Electric motors are incredibly reliable, they don’t need a lot of maintenance,’ explains Matthew.

While EVs are still relatively expensive compared to ICE vehicles, they cost less to run overall.

However there are still considerations for the long-term future of electric vehicles and their components.

‘I think we’ll have to get much more serious about recycling for the longer term,’ says Matthew.

Despite the ongoing challenges, this time, it appears EVs are here to stay.