The chance discovery of one of Victoria’s oldest fossil plants, 400 million years in the making

A series of unlikely events that led to the discovery of a 400-million-year-old fossil, shedding new light on the evolution of Australian plants.

On a hot January day in 2015, Fearghus McSweeney happened upon a miraculous fossil find.

It was in an unlikely place too—a roadside on Taungurung country, near the central Victorian town of Yea, about 100 kilometres north of Melbourne.

‘It’s on the main road, so the cars zoom past there. It’s actually not a great place to be looking for fossils,’ says Fearghus, a palaeobotanist at RMIT, who specialises in early land plants.

‘At the time I was more of an amateur, just doing this as a hobby.’

He was with an expert though, Dr Michael Garratt, who had previously studied the spot.

‘We just said we’d have a look.’

A few minutes later, recalls Fearghus: ‘It was literally the first few blows of the hammer…it popped out and I split the rock.’

‘It was just there; I was really surprised.

‘That has never happened, and I doubt it will ever again, it was really very lucky.’

What he had found was an entirely new genus, and one of Victoria’s earliest plants, Fearghus and his co-authors have described in the scientific journal Memoirs of Museum Victoria.

And while the story of the find itself is incredible, what the plant had to go through to get there is even more remarkable.

A barren land

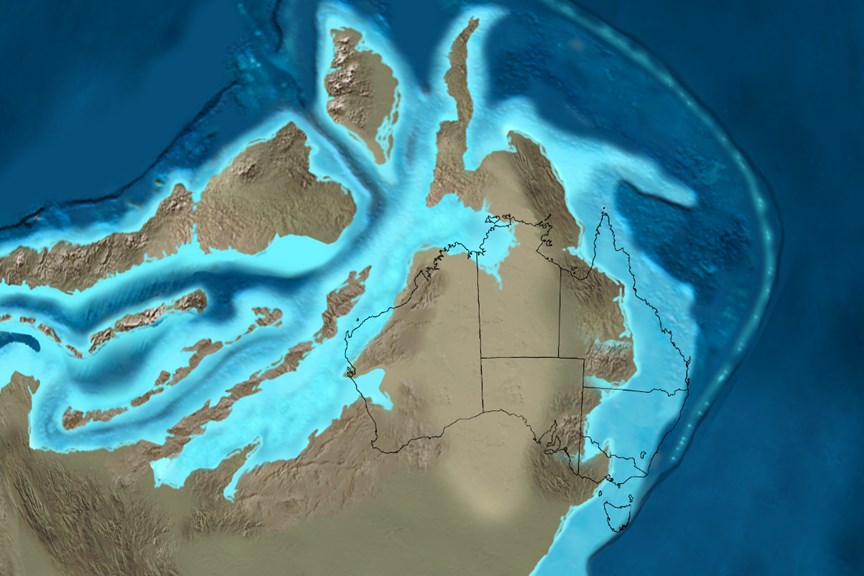

400 million years ago, in the Early Devonian Epoch, the land we now know as Victoria was largely underwater.

Australia was attached to the supercontinent Gondwana, and our ancestors were still getting around with fins.

It was a warm, harsh, unforgiving landscape; oxygen levels were lower than today and ultraviolet radiation higher.

Some fungi were massive, such as Prototaxites towering metres above anything else.

Amongst all this were the earliest forms of vascular plants trying to gain a foothold on land.

Vascular plants use conductive tissues to transport food from root to tip and support their own weight.

‘The first plants, which were non-vascular, were quite similar to what mosses look like,’ says Fearghus.

‘They were really small, so they had to evolve a vascular system in order to get much bigger.’

Taungurungia garrattii is an early example of this, that grew to about 20 centimetres high.

‘The only other plant that would have been bigger in Victoria was the lycopod Baragwanathia…that grew up to 2.7 metres high.’

Most plants from this period fall under three categories—rhyniophytes, lycophytes, and zosterophylls; zosterophylls being further divided into two groups.

Taungurungia garrattii, explains Fearghus, ‘Is a mish-mash of different characteristics from these two zosterophyll groups’

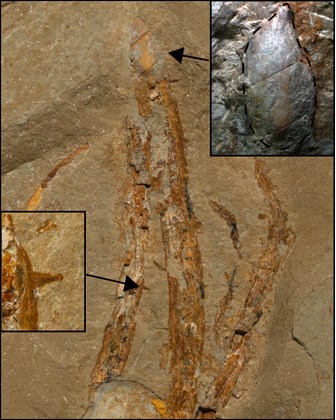

It also has abnormally large fruiting bodies, known as sporangia, that allowed it to generate spores to reproduce.

‘The size of the sporangium is absolutely massive, it’s huge compared to anything I’ve come across,’ says Fearghus.

‘At least double to triple the size of most.’

Which would have required a lot of energy to grow.

Plants use photosynthesis to convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into energy in the form of glucose.

And Taungurungia garrattii is no different, except that this was millions of years before the appearance of leaves.

‘It has what’s called emergences on it; they look like little triangles on the stem,’ explains Fearghus.

‘What these appear to be is an area for increased photosynthesis…and are akin to an early form of leaves.

‘These emergences are not common in plants for Victoria, there are only a small handful that have them.’

Only Victoria’s Baragwanathia had what we could easily recognise as leaves, called microphylls, which were narrow and strap-like with one central vein.

Long way from home

Another challenge prehistoric plants had in these early years was a lack of soil to support them, which is part of the reason Fearghus found the plant where he did.

‘Because there was very little soil and there were very few plants affecting the flow of rivers, rivers didn’t meander as much,’ he says.

‘They tended to flood out onto the plains and push everything with them.’

While it is impossible to know exactly where this ancient plant originally grew, Fearghus says it was most likely from what is now western Victoria (that was above sea level at the time) or Antarctica (it was still attached as part of Gondwana).

So, it would have been a big flood to bring it all the way to what is now central Victoria.

‘It was likely growing along the banks of a river or marshy area and all that stuff would have been pushed out with a debris flow…before falling out of the water column and settling on the ocean floor and then covered with sediment.’

Once sealed away from anything that would destroy the plant, it had to be undisturbed for millions of years while subjected to massive pressure and heat.

‘That’s how the plant de-gasses, loses water, and eventually mineralises resulting in the fossil we see today,’ explains Fearghus.

The likelihood of this happening though is infinitesimally small.

‘It is a very rare event so we are very fortunate to have it.

‘The vast majority of life on earth will never fossilise,’ says Fearghus.

The next hurdle in Taungurungia garrattii‘s path came about 10 million years later, when Victoria was subjected to a lot of tectonic activity.

‘What was part of Victoria then was compressed and about 40 per cent of it was lost, so we could have lost the land that it came from,’ says Fearghus.

Fortunately, though, the fossil was instead pushed up out of the water with the land, bringing it closer to the surface.

While this was happening, what may have been this plant’s distant relatives were evolving into trees and beginning to congregate as forests, filling the atmosphere with oxygen.

Larger and more complex life took advantage of this kinder environment and, over the next few hundred million years, evolved into the humans who built the road right next to it.

There it remained, undisturbed, until the day Fearghus came along with his hammer.

‘I was bagging and numbering specimens because I was hoping one day I could give them to the museum and have someone else describe them, I wasn’t planning to do it myself.’

Fearghus studied the plant as part of his doctoral thesis on early Victorian land plants, and it took six months of painstaking work to prepare the fossil.

When it came to a name for this new genus though, he says that was an easy decision.

‘That was one of the first things that popped into my mind—wouldn’t it be nice to name it after the Indigenous people of the area.’

Fearghus was granted permission by the Taungurung Elders to use the name Taungurungia.

He named the species garrattii in honour of Dr Michael Garratt, who helped to find the fossil.

As for the fossil itself—it has now reached the end of it 400-million-year journey and resides in the Melbourne Museum, as part of the Victorian state collection.