Scienceworks is 30!

Jump on board for a look back at Scienceworks’ past, and some secrets, as we celebrate its 30th birthday.

Can you believe Melbourne’s much-loved science and technology museum is 30 years old?

When it opened on 27 March 1992, Scienceworks was the first major new museum built in Melbourne for more than 100 years!

There is no better time to explore Scienceworks’ past, and some lesser-known details, about the building and its surrounds.

It almost wasn’t called Scienceworks

It is hard to imagine a more appropriate name for this museum and, while it took nearly two years to come up with, it wasn’t the only option on the table.

Of the 150 names considered in the early stages, only one other was recommended—EXOS, formed from Exposition Of Science.

It was ruled out after someone noticed it was close to the Greek word ‘exo’ (to go out).

As the museum’s former head of education, Sally Hirst, explained back when it first opened, ‘We wanted to do something about the way science works—what it means to people and why you need to know about science.

‘So we put the two together…and it kind of clicked.’

As it happened there was also a shop in Clifton Hill called Scienceworks, but the owner was kind enough to let the museum use the name.

Running down a dream

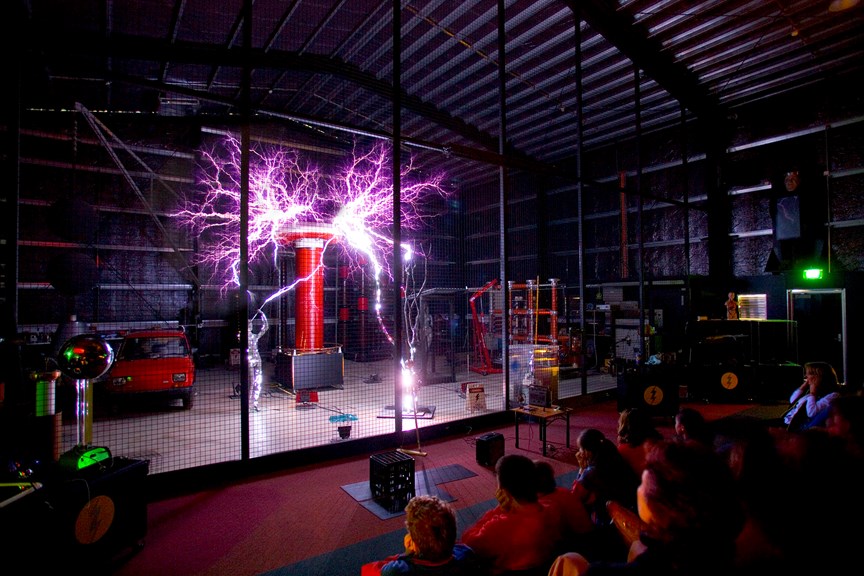

Originally there were four ‘permanent’ galleries, covering the areas of Materials, Transport, Inventions and Energy, and a touring exhibition space.

But ask anyone who grew up with Scienceworks and there is one exhibit that comes to mind.

Millions of people have taken the chance to test their speed against the legendary Cathy Freeman in the Sportsworks exhibition, but few have outpaced her.

However, Cathy Freeman has only been there since 2000 to coincide with the Sydney Olympic Games.

When Sportsworks first opened, visitors raced against another Olympic track star—Jane Flemming.

The popularity of this challenge has kept people coming back time and time again, making it the museum’s longest running (pun intended) exhibition.

Out of this world

Did you know the team behind the Scienceworks Planetarium is the only planetarium production crew in southern hemisphere?

Not only this, but their work goes all over the world and is translated into dozens of languages—including the adventures of Tycho.

Melbourne’s first planetarium was opened in 1965 in the museum’s old home, what is now, the State Library of Victoria building.

When the new planetarium opened at Scienceworks in 1999, it was so big that the old dome would fit in the foyer.

It was also the first Australian planetarium set up with digital, rather than optical, technology—a given nowadays but advanced for its time.

Behind closed doors

Scienceworks is much more than it seems.

Beyond the public exhibitions, it also houses an extensive collection of science and technology objects from throughout the ages—about 44,000 objects, and that doesn’t include the 70,000 individual pieces of trade literature.

In the collection store you’ll find significant examples of everything from cars, bicycles, and motorbikes to computers, robots, and medical technology.

The oldest object is a table clock from 1630, while the newest acquisition is, appropriately, a COVID-19 swab kit.

Scienceworks also has its own engineering workshop, used to restore, and maintain, working machinery and significant historical pieces like the Great Melbourne Telescope.

Home of machinery history

If you’re lucky enough to be at Scienceworks on the right day, you might hear the distinctive sound of a steam whistle off in the distance.

It is usually a sign that the engineering team has fired up an engine, like this Cowley Steam Traction Engine from 1916, to give it a run around the arena.

But they’re not just going for joyrides—these machines need to be kept in working order for conservation, and the only way to do that is to use them!

Tunnels everywhere

It was a little over 30 years ago that the Spotswood Pumping Station became part of Museums Victoria and part of the new Scienceworks precinct.

Being built on a site shared by the 125-year-old engineering marvel, Scienceworks links Melbourne’s industry, heritage, and applied technology.

But what links everything is the network of underground tunnels and pipes built to transport Melbourne’s wastewater.

The pumping Station was built on this spot in the 1890s because it is close to the Yarra River and one of the lowest points in the city.

It’s not the most glamourous history but it is something we should all be very grateful for—it saved us from the moniker ‘Marvellous Smellbourne’.

Shelter from the storm

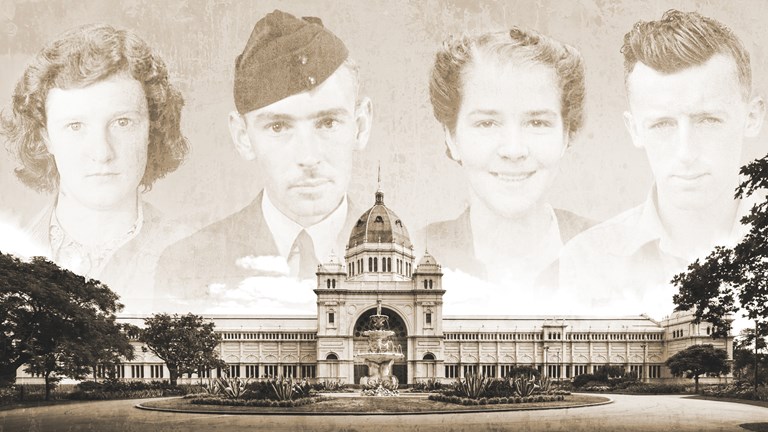

During World War II the Pumping Station was seen as a potential strategic target—not just as an essential piece of infrastructure but also because it was next door to an armaments factory.

While air raid shelters were being dug all over Melbourne, three bunkers were installed next to the Pumping Station to protect the workers.

Fortunately they were never needed, and you can still see the entrance to the central bunker in the main courtyard just next to the stairs that lead down from the arena.

This one was used as a central communications command for air raid wardens, while the other two were at the northern and southern ends of the Pumping Station.

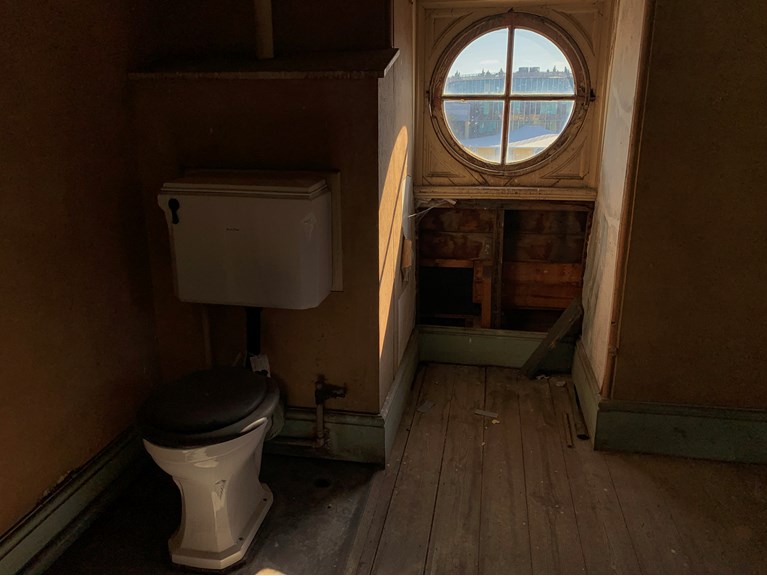

A loo with a view

Imagine having your own private toilet, at the top of a tower, with a great view of Melbourne’s western suburbs.

Well, Lucey Alford didn’t have to imagine—it was one of the perks of the job when, in 1941, she was the first woman employed in a technical role by the Board of Works (now Melbourne Water).

The 26-year-old scientist was hired as an assistant bacteriologist and her lab was set up at the top of the south engine house tower.

‘Toilets and things, you see, they had to build a special one. Women were not employed on the technical staff,’ Lucey recalled.

This special toilet was installed in a small room off the landing, next to her lab.

She had to climb 78 steps to get to work though so, despite the view, Lucey was probably relieved when laboratory staff were transferred to offices in South Melbourne two years later.

Mad movies

You can’t talk about the Pumping Station without mentioning Mad Max.

George Miller’s 1979 cult classic featured the Pumping Station as the base of the Main Force Patrol.

But the building’s French Second Empire architectural style has also attracted dozens of other Australian film and TV productions over the years.

Notably, you’ll spot it in Prisoner, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries and Spotswood—starring Anthony Hopkins, Toni Collette, Russell Crowe, and Ben Mendelsohn—which was released in the lead up to Scienceworks’ own grand opening.

Designed to reflect

Melbourne’s western suburbs are a hive of industrial activity, even to this day, and Scienceworks was deliberately designed to fit seamlessly within that environment.

Everything from the shape of the central building that references the giant oil storage tanks nearby, to exposed internal ducting to show the inner workings, help to keep the building relevant to the context of the area.

One of the big reasons for its enduring popularity is also that Scienceworks is a place for doing things.

There is nowhere quite like it and half a million people come though the doors every year, including 84,000 students from more than 900 school groups.

While the building and exhibitions have grown and changed over the last 30 years, the core philosophy of Scienceworks has stayed remarkably consistent—helping kids and adults experiment, explore and learn how science works!