Rhyll Plant: sowing the seeds of scientific art

Half a century as a scientific artist at Museums Victoria has taken Rhyll Plant to some unexpected places, but where did it all begin?

It has been more than 50 years since Rhyll Plant started creating scientific illustrations at Museums Victoria, but it wasn’t always her plan.

Inspired by her mother Joyce’s interest in natural history Rhyll spent hours during her childhood scouring Phillip Island’s beaches and rockpools before graduating to the exploration of fossil beds, drawing and collecting the specimens she found.

In 1966, a 13-year-old Rhyll donated a fossil shark tooth to the museum and was ‘delighted to receive a certificate’ signed by director John McNally as a reward for her efforts.

It seems only natural then that Rhyll would end up at the museum.

‘I began my museum career with the requisite high school qualifications, a folio of drawings and lots of enthusiasm,’ she says.

When Rhyll began her career in 1970 the National Museum of Victoria (now Museums Victoria) was located in the building that is now home to the State Library of Victoria.

‘My own space under a window, stared at by both the glass eyed stuffed specimens in transparent cases lining the corridor and the school kids lining the street above’, she recalls.

A broad brush

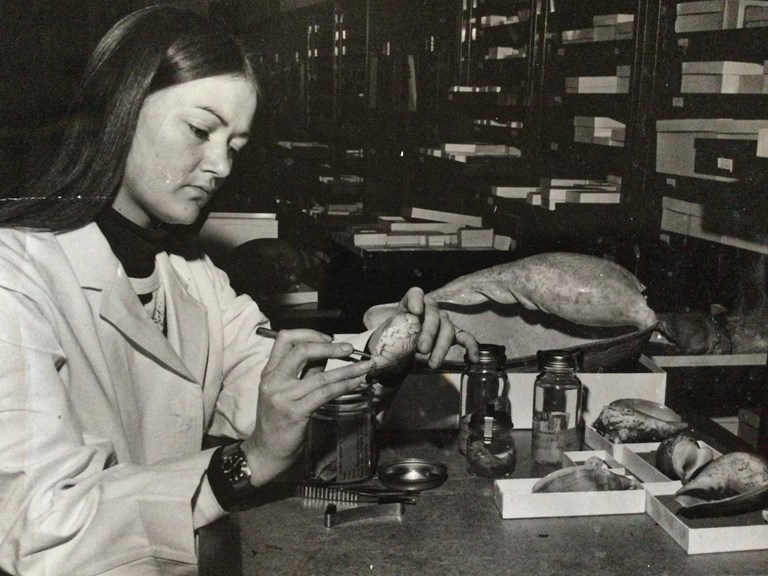

Rhyll first joined the museum as a technical assistant—a role similar to that of a present-day collection manager that she describes as ‘broad but never dull’.

Her day-to-day job involved identifying, registering, cataloguing, and preserving specimens, assisting with research projects, museum displays, and field work but it also included ‘other duties as directed’.

‘Technical assistants were multi-talented,’ says Rhyll.

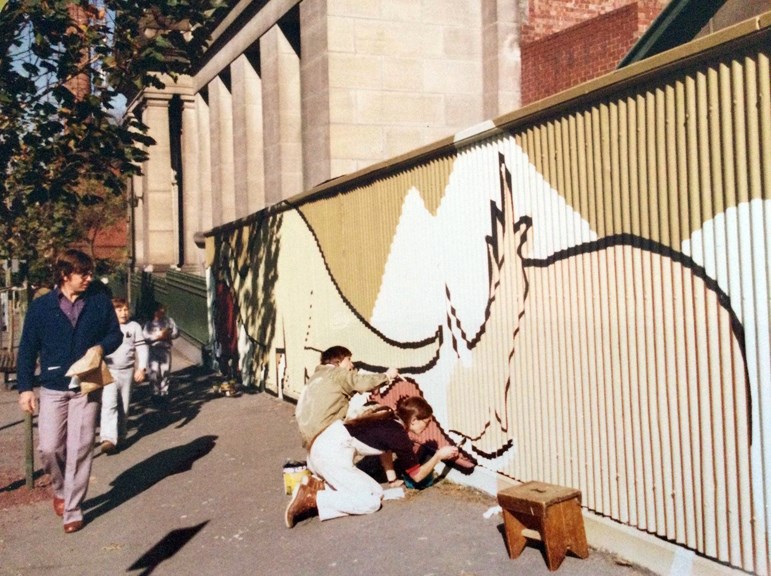

‘I was dressed up as Phar Lap’s jockey for his excursion to Flemington, helped guide a model pteranodon down the side of the Russell Street building, painted dinosaurs on the fence, and airbrushed display panels.’

And it was here that her skills as an artist came into their own.

‘Though there was no lack of guidance in my technician role, no course existed in Australia to teach me scientific illustration techniques, so I learned by my own trial and error.

‘Illustration, though not part of my job description, became a focus of my time at the museum when it was seen that my skills in this area could be useful.

‘From my point of view, my passion for natural history and art could not have been fuelled to better advantage,’ says Rhyll.

And where better to use those skills than on a marine research voyage?

A promotion to technical officer gave Rhyll the chance to join the crew of the RV Soela to eastern Bass Strait and off Gabo Island in 1985.

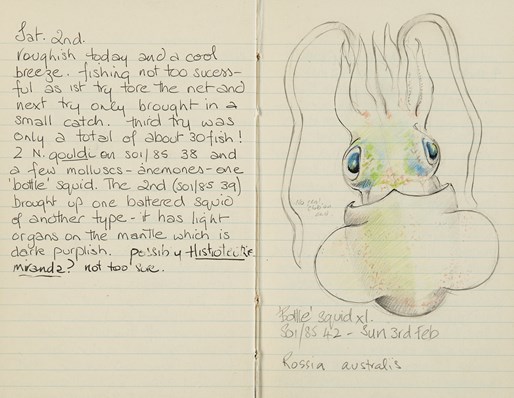

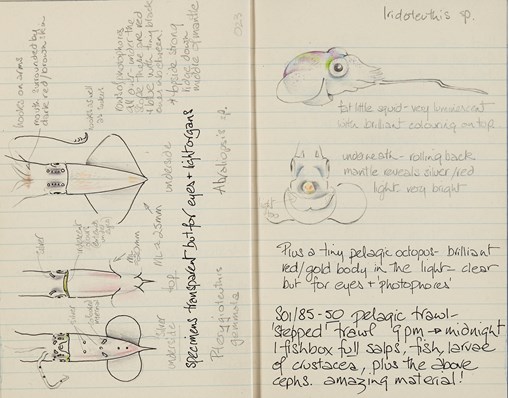

She kept a field diary and made sketches, filling its pages with coloured illustrations of urchin, cuttle and strange squid, and notes of a fish catch.

‘Cameras likely do today what I did on board the Soela, quickly securing an image of a slippery specimen to capture its colour and shape before it shrunk and faded, all the while braced against the roll of a ship.

‘Drawings have the advantage of isolating and recording detail and field notebooks are a rich resource with sketches often made in testing conditions.’

And those sketches have come in very handy in the years since.

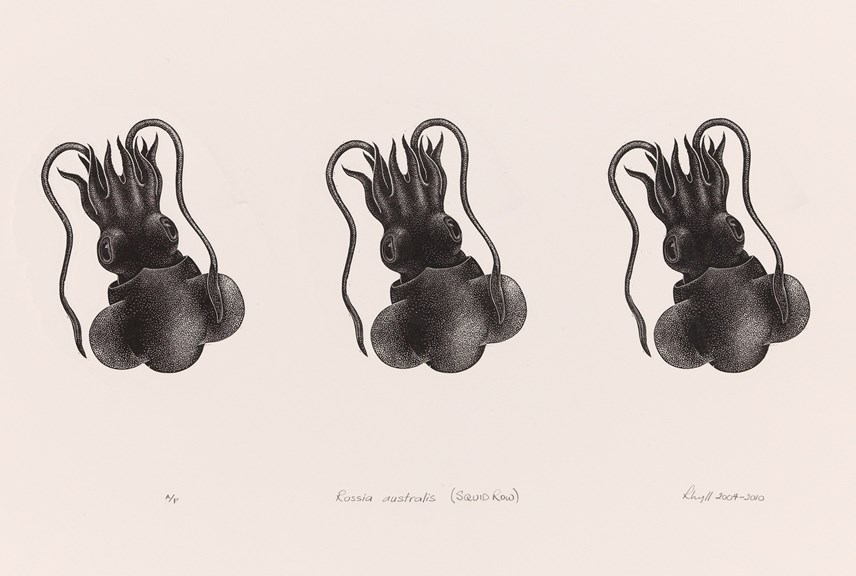

‘There is a 20 year gap between my 1985 field sketch of Rossia australis and my using it as reference for my 2005 wood engraving Squid Row.

‘In reviewing the old journals I am transported back to the time I illustrated them and delight in their originality.

‘I impress on students the value of such notes as “aides de memoir” for their art.’

Making her mark

Rhyll has supplied illustrations for several scientific publications, notably those authored by Curator of Invertebrates Dr Brian Smith and Honorary Associate Ron Kershaw, including a Field guide to the non-marine molluscs of south eastern Australia, and Dr Julian Finn’s Taxonomy and biology of the argonauts.

‘Rhyll’s scientific illustrations have provided such elegant solutions for researchers over the years,’ says Melanie Mackenzie, collection manager of marine invertebrates at Museums Victoria.

‘Her drawings are beautiful but, more importantly, accurate.

‘They bring together a huge amount of scientific information in one place, without having to worry about missing a diagnostic feature from certain angles or dealing with damaged limbs like you’d get with a photo.’

Rhyll’s artwork has also found a life beyond a solely scientific purpose—appearing in the Melbourne Museum exhibition, and book, titled The Art of Science, something she describes as ‘an honour for its recognition of my long and ongoing journey through science, art, and humour’.

While Rhyll says ‘I could not, pre-1988, have imagined myself leaving my job at the museum for any reason’, life had other ideas.

She left the museum in 1990 to raise twins, but kept her ties as a freelance illustrator, before returning as a research associate in 2002.

Rhyll’s career also made for an interesting upbringing for her children, Jess and Kim McGeachin.

‘My sister and I delighted in telling friends that you needed to be careful opening the freezer in our house as you never know what specimen was waiting to fall out,’ says Jess.

And just as Rhyll’s mother passed on her interest in natural history, Jess has also been inspired by his own mother’s passion.

‘Her love for art and nature had inspired me to follow a career as an illustrator and graphic designer, now working for Museums Victoria too.

‘I’m very proud to be drawing alongside her.’