Resurrected: native Australian mouse back from extinction

How 160-year-old museum specimens helped to bring a species of native Australian mouse back from the dead.

Having the highest rate of mammalian extinction in the world is not a record to be proud of, but scientists have now revived the fortunes of one native Australian mouse, using specimens from Museums Victoria’s collection.

They have taxonomically resurrected Gould’s Mouse, a species thought extinct for more than 160 years, by finding it is the same species as the Shark Bay Mouse.

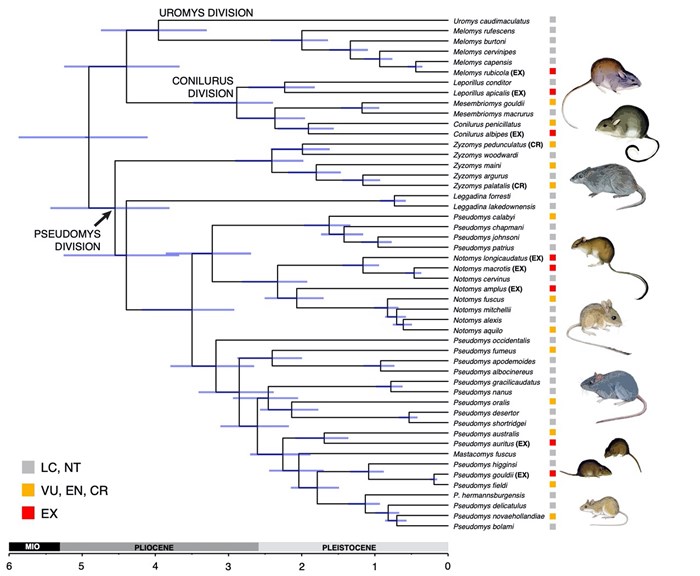

The finding comes from a new study, published today in the journal PNAS, in which researchers genetically tested eight extinct species of native Australian rodents, and their 42 living relatives, to examine the decline of endemic species since European arrival.

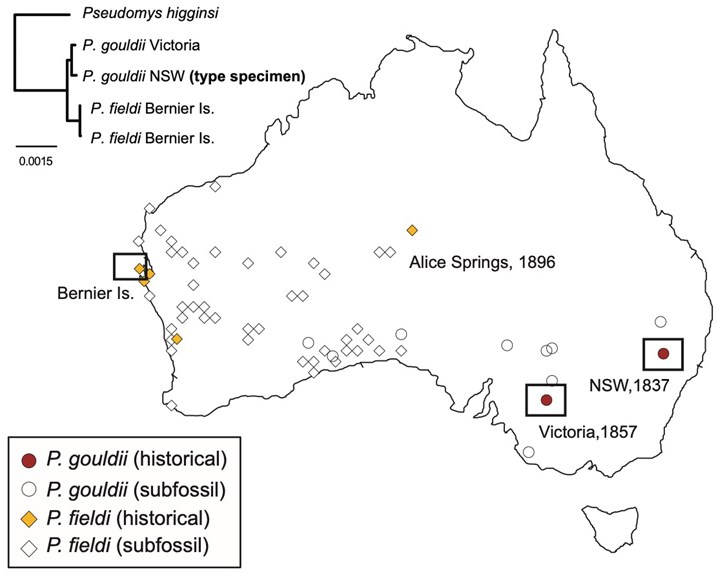

One of those species, Gould’s Mouse (Pseudomys gouldii), was confirmed to be visually and genetically indistinguishable from the Shark Bay Mouse, or Djoongari (Pseudomys fieldi), which is now only found in an island population in Shark Bay, Western Australia.

‘It’s very exciting, I think everybody likes the idea of removing a species from the ever-growing list of extinct species in Australia,’ says the study’s lead author, Dr Emily Roycroft.

34 Australian mammal species have been declared extinct since Europeans arrived on Australia’s shores in 1788 and native rodents account for about 40 per cent.

‘We get to take a name off that list, which is great, but at the same time is quite sobering,’ says Dr Roycroft.

‘It highlights a bigger issue…how quickly things can go catastrophically wrong for native species.’

Hiding in plain sight

Taxonomy refers to the scientific system for naming and classifying organisms.

It’s highly regulated, so taxonomically resurrecting a species from extinction isn’t something that happens every day.

‘It's pretty rare phenomenon but it's more common Australian almost anywhere else,’ says Dr Kevin Rowe, Museums Victoria’s senior curator of mammals and one of the study’s authors.

‘The Leadbeater's Possum was last seen in the 1930s and then found again in 1961, and so was resurrected from extinction by finding living animals,’ he says.

In the case of Gould’s Mouse though, its revival relied on specimens that had been sitting idle for more than 160 years.

Before now, the last time anyone conclusively documented a sighting of Gould’s Mouse was on William Blandowski’s expedition to the Murray River, on the Victoria-New South Wales border, in 1857.

One other specimen was collected in NSW 20 years earlier by Charles Darwin's expedition to Australia in the 1830s.

‘And then the species was never seen again,’ says Dr Rowe.

‘It was a really narrow window in which science had an opportunity to get a sample of a living specimen before it disappeared.

‘For most of Australia when the extinctions happened in the early part of the 20th century or latter part of the 19th century, we have very few records—and those fortunately were preserved in museum collections.

‘Now 160 years later we're making use of those specimens to recognise that the living species in Shark Bay was actually a continental wide mouse that once lived from Shark Bay all the way to NSW.'

Dr Roycroft says it’s not a result they were actively looking for.

‘I was surprised by it,’ she says.

‘Because they're so geographically separate, we initially expected that populations in Victoria and New South Wales would be quite genetically different from an island population off the coast of Western Australia.’

The species will still be known by the common name Shark Bay Mouse, or Djoongari, while reverting to the original scientific name Pseudomys gouldii.

Rapid decline

In addition to Gould’s Mouse, the study examined seven other extinct native species: the White-footed Rabbit Rat, Lesser Stick-nest Rat, Bramble Cay Melomys, Short-tailed Hopping Mouse, Long-tailed hopping Mouse, Big-eared Hopping Mouse, and Long-eared Mouse.

Dr Rowe says all of these were found to have relatively high genetic diversity immediately before their extinction, suggesting they had large, widespread populations.

‘They weren't already in decline; they died out because humans introduced something dramatic to alter their fate and the landscape.’

Dr Rowe has a fondness for native Australian rodents, and even moved from his home in California to study them.

He says genetic diversity is vital to a species’ survival and can be used as a measure for population collapse because animals become less genetically diverse if they are in-breeding.

Some extinct Australian mammals, like the Tasmanian Tiger, were already struggling with low genetic diversity before European arrival.

‘There were other factors that led to their decline, and then we just kind of pushed them over the edge.’

Dr Roycroft says the findings demonstrate genetic diversity does not provide guaranteed insurance against extinction.

‘The introduction of feral cats, foxes, other invasive species, agricultural land clearing and new diseases…absolutely decimated native species that were otherwise relatively stable and potentially had quite large population sizes,’ she says.

Misconceptions

At this point, some people may be wondering, what does it matter if we lose a few mice?

For starters, these are native species.

Rodents may have a bad reputation in Australia, but that’s largely not the fault of those that have evolved on the island continent over the past four million years.

‘Native mice are very different to invasive mice,’ explains Dr Roycroft.

‘Almost all of the species, you'll never find them near someone’s house, they'll never be seen during daylight—they are very elusive.

‘That's one reason they are so threatened…they cannot really live anywhere near human habitation, or at least in built-up areas.’

Native rodents play an integral role across Australia by eating plants and invertebrates, acting as prey for other native species, and as ecosystem engineers—changing their environment to benefit themselves and other species.

‘We've lost a lot of biodiversity and we need to be very careful about what we do from here, in terms of conservation and management of native species, because there is still a lot more that we stand to lose,’ says Dr Roycroft.

What next?

The problem for the Shark Bay Mouse now, is that it has far less genetic diversity than the species originally had when it was distributed across Australia.

But Dr Rowe thinks there may be a chance to recover some of that lost diversity.

‘By knowing the genetic diversity that was in species prior to their extinction or prior to their decline, we can potentially resurrect that genetic diversity in living species through some of the genome editing methods that are becoming available,’ he says.

‘There's some potential that this information allows us to be aware of what we took away from nature, and put it back in.’