Learning from Australia's bushfire past

How can the Victorian Bushfires Collection, and the stories of Black Saturday survivors, help prepare us for the future?

Dr Peg Fraser has seen and documented some incredible feats of bushfire survival and endurance.

She is an oral historian, author of Black Saturday: Not the end of the story and one of the curators who developed the Victorian Bushfires Collection at Museums Victoria, where she is an Honorary Associate.

Peg now volunteers with the Australian Red Cross, using the knowledge she gained during the process to help people recover from bushfire.

‘All the things that I have learned through Black Saturday can help people in future bushfires and natural disasters,’ she says.

‘As a historian I think the most important question that history can answer it is—how did we get here today, and where are we going to go?’

Documenting a disaster

In the wake of Black Saturday, Australia's worst natural disaster, Museums Victoria set up the Victorian Bushfires Collection to document the devastation and its impact on communities.

The collection’s first curator was Liza Dale-Hallett, who worked alone for several months before she was joined by Rebecca Carland and Peg Fraser, collecting items and stories from survivors.

‘We had a very intensive year of collecting,’ says Peg.

‘A lot of the objects we were collecting were extraordinary physical artefacts showing the effects of the fire—like the old Holden, and the pools of aluminium that had melted and then solidified.

‘But we felt there was a real danger of those objects becoming relics, with great emotional power but not much insight into people’s experiences.

‘What we needed were the stories behind those, the experiences of the people, so that we could look more deeply into those objects and reflect not just on the physical effects of the fire, but also on the impact on people.’

Peg spent hours with survivors, recounting their stories, but not everyone was able to be so forthcoming.

‘It took some of them more than three years to say, “OK now I trust you enough to do an interview with you”, because a lot of these people got burned out with the media in the days immediately after the fire,’ she says.

‘They didn't want to be doing this, they wanted to get on with their lives.

‘I had a lot of people say, “I am so tired of the media, I'm so tired of people studying us, but this is for the museum so I will do it”.

Peg was drawn to the small town of Strathewen, northeast of Melbourne.

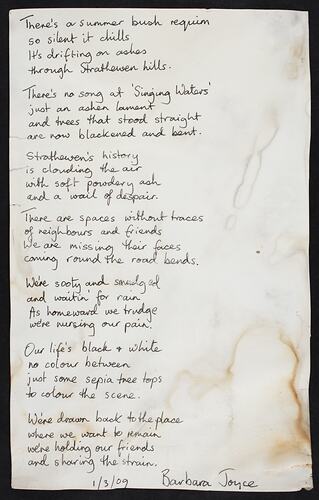

‘I was looking through material I had collected, and I came across a photo of the poetry tree,’ she says.

‘It was a manna gum that was at the bridge in Strathewen…and some of the residents had started posting poems on the poetry tree just days after the fire.

‘And I discovered that not everybody loved the poetry tree—it was a very contested site.

‘The poetry tree became an example of all of the stories after Black Saturday, that it was complex and messy and fascinating, and I think the day I realised that was the day I really began to work.’

The local primary school and its principal, Jane Hayward, were also a big factor.

‘The school burned down, 80 per cent of Strathewen was destroyed, there was a very high fatality rate there,’ says Peg.

‘The day after Black Saturday they had a community meeting and Jane said, “We're reopening the school” and they reopened in borrowed classrooms on Wednesday, four days later.’

When Peg arrived in Strathewen, every person she spoke to was clear about who needed to be acknowledged.

‘At almost every point along the way people said, “Oh you have to talk to Jane, and you have to get the hard hat”, and the hard hat is now in our collection.’

‘It was actually made and decorated by a student,’ says Jane.

‘It’s a special piece of equipment, it’s seen some interesting times.’

Jane wore it to fortnightly site meetings, while the school was rebuilt on its original grounds.

Peg says, ‘People felt so strongly about getting the hard hat because it became a symbol for them that the entire community, the entire area, was going to be to be able to continue.’

Bushfire education for, and by, children

After Strathewen Primary was rebuilt, Jane and her community started to develop a world-first program to teach children how to plan for bushfires.

Students were taught how to calculate fire ratings themselves and be aware of the risks in their environment, and it’s a program that continues to this day.

Scarlett Harrison was a toddler during Black Saturday, but years later she has become an ambassador for Strathewen’s bushfire education program.

‘We made films, we made some advertisements, to share and project our knowledge to the community and wider areas,’ says Scarlett.

‘We explained what to do if a bushfire came through, how to prepare…how to know what to do.’

It has been recognised nationally and internationally as an example of best-practice disaster education for children, and was the basis for a recovery program for the Grenfell Tower fire in London.

Jane says the students also help to design the program every year.

‘Knowledge is just empowering for our children,’ she explains.

‘My aim from the get-go, it was all about teaching our kids what it involved, living in an area of high bushfire risk, and how we could get them to learn to love where they lived and trust and feel safe again.’

Peg says she is in awe of the work that Jane and the school community have done in bushfire education.

‘A lot of people might find it confronting to see children working on bushfire risk,’ says Peg.

‘But what these children are learning is what we should all be learning, because with rapidly increasing climate change we're entering a new world.

‘In a way, we're all going to be children—we're going to have to learn new skills and new ways of doing things,’ she says.

Looking to the future

At the end of the collecting project, Peg found she still had more to do and started a PhD in history.

‘I had so many mistaken preconceptions of what it would be like to survive a fire like that and to recover.

‘I thought, “I've barely even scratched the surface of this”.

‘I was aware when I was doing the PhD, and continuing to interview people, that it was costing them a lot to do these interviews—not so much in time but in terms of the emotional effort, in the intellectual effort, that they were putting into it—and I felt that I owed them something more than a thesis sitting on a shelf.

‘And that's when it became a book.’

Peg’s book Black Saturday: Not the end of the story was published in December 2018, to wide acclaim.

It won the Victorian Community History Award for oral history in 2019, and Oral History Australia’s inaugural book award in 2020.

‘Somebody said to me, “We don't need another book on Black Saturday”—well, actually, we do,’ says Peg.

‘We need many more books on Black Saturday because natural disasters are going to become increasingly a part of everyday life in Australia and we need to be able to learn from them.’

And that is intrinsically linked with the Victorian Bushfires Collection.

‘I think the Collection is going to be a very useful and valuable tool for navigating the future,’ says Peg.

‘Official studies and the Royal Commission reports are very valuable, but quite remote from the actual experiences.

‘Media reports, and some of the books that came out immediately after Black Saturday, they’re at the opposite end—they’re very personal.

‘I think that the Bushfires Collection is the connecting point between those.

‘It makes the connection in terms of the social context.

‘That's quite a unique thing for the Victorian Bushfires Collection to be doing.’