How much has cycling changed over the last 100 years?

A lot can change in 100 years, especially when it comes to cycling, but does the gear and advice of an Australian champion like Hubert Opperman stand the test of time?

Cycling is more than just a form of transport, recreation, or competition; it is often a part of someone’s identity—something many know all too well.

And you might think that the experience of any serious cyclist these days would be worlds away from those 100 years ago (except maybe for those who have rediscovered the joys of penny farthings), but how true is that?

Well, fortunately here at Museums Victoria we have some insight in a letter written by an Australian champion.

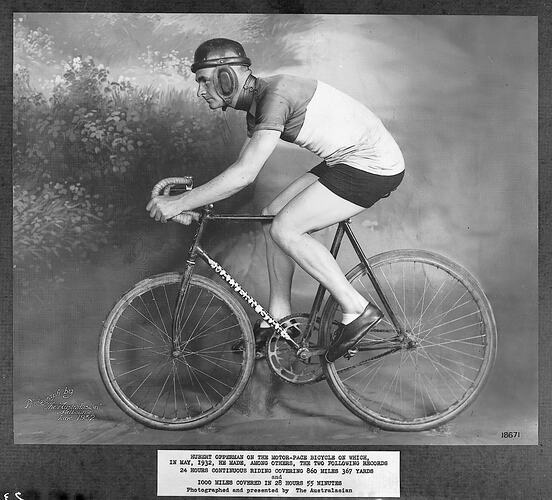

Sir Hubert Opperman, or Oppy, was a legend in his day who held numerous long-distance records and competed in the Tour de France and Bol d’Or (which he won).

‘In his day he was the most well-known Australian sportsman in the world,’ says Matilda Vaughan, curator of engineering at Museums Victoria.

‘The highest cycling award in Australia is even named after Oppy.

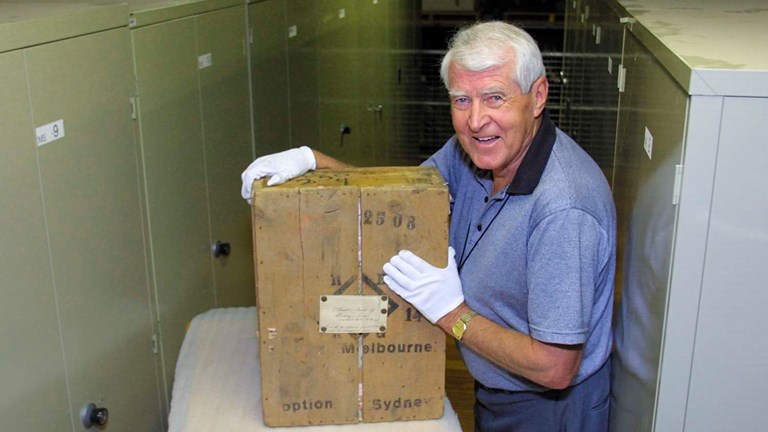

‘The museum is fortunate to hold many of his cycling trophies, donated by him, and two bicycles from his record setting rides.’

Oppy knew a thing or two and, fortunately for us, he was more than happy to pass that knowledge on to cycling enthusiasts looking to follow in his tyre tracks.

‘I love this letter because it demonstrates his ongoing commitment to young riders and encouraging them—he always made time for his fans,’ says Matilda.

The steed

‘The first essential is a suitable bike for your build,’ wrote Oppy in his letter to a young cycling enthusiast in 1938 who asked for training tips.

Sound advice, and it is likely what you would hear when purchasing a new bike now—but here is where we start to get into the differences, because you have a lot more choice these days.

Oppy’s Malvern Star racing bicycle (state-of-the-art in its day) has a tubular steel frame, and weighs 12 kilograms.

Compare that to modern racing bikes that are made almost entirely of carbon fibre, and you start to see just how far technology has come.

Ok, the modern bikes must not weigh any less than 6.8kg because of competition rules set by cycling’s governing body but most companies have to add weight to comply.

The weight difference is even more amazing when you consider that Oppy’s racing Malvern Star was a single speed; modern bikes have anywhere upwards of 12 speeds and disk brakes, which should add considerably more weight.

Despite having been invented in the early 1900s, changeable gears were banned from the Tour de France until 1937.

Oppy’s advice was to train on a fixed wheel bicycle and choose gearing to suit your style of riding.

‘Coaches and trainers today still get riders to pace behind a motorbike with a fixed gear bicycle on a velodrome to improve their endurance and technique,’ says Matilda.

‘So in that sense Oppy’s advice still stands today.’

But if we really get down to it, price is often the determining factor in choosing a bicycle—and performance does not come cheap, whatever the era.

In the 1930s Malvern Star (and BSA in Europe) offered a high-performance Opperman Model, which even came with an option for 3-speed gears, starting at just over £10.

While that is about $1000 in today’s money, keep in mind the average weekly wage at the time was less than £4.

If you are looking for Oppy’s race-spec equivalent these days, it will probably set you back at least 10 times that price.

Having said all that, you have probably noticed that the overall shape and basic design of bicycles has not changed all that much since the early days.

What we now recognise as the standard bicycle shape first appeared in the late 1880s when they were marketed as ‘safety bicycles’ in comparison to the penny farthing, which positions the rider much higher from the ground.

Just because modern bicycles are safer though, that does not mean you should skimp on protective equipment.

Protect yourself

Another area that has changed significantly over the years is head protection.

‘More often than not Oppy is seen without a protective helmet, as we use today,’ says Matilda.

‘When he was wearing one, it was usually was attempting to break a speed record while being paced behind a motorcycle.’

In this case Oppy wore a steel and leather helmet, whereas bike riders today have aerodynamic, lightweight helmets made from carbon fibre and expanded polystyrene.

‘Our helmets today give you some protection from impact, while back in Oppy’s time it was more about stopping head abrasions,’ says Matilda.

Aside from weighing about half as much, modern helmets are also much better ventilated, far more adjustable, and so much better at protecting your precious brain from concussions.

You also have a lot more choice in clothing.

Oppy’s recommended riding gear was, ‘modified golfing plus fours, stockings, sweater, a beret, and “Tour de France” shoes’—that’s a lot of wool and leather!

Wool does have the advantage of being able to breathe even when it is wet (and it will get very wet from rain or perspiration), but it also becomes heavier the more liquid it absorbs and there is chafing to contend with.

So be grateful for the technological advances like Lycra, which allow cyclists to hit the road with more freedom of movement and a lot less smell (thank you antibacterial coatings).

Your sleeker, lightweight, gear might make riding more comfortable but, as Oppy appreciated, you still have to do the training.

Keeping focus

This is one part of Oppy’s advice that has stood the test of time, at least for most people, is how to get the most out of your training—and as they say, you are what you eat.

Your pre-training breakfast might be a bowl of porridge and fruit for breakfast and you may pop a couple of protein bar and a banana in your pack for snacks on the road.

Back in 1938, Oppy was recommending the same: ‘Fruit, nuts and raisins are excellent’ and ‘always carry some in your food bag when training’.

And for all the advancements in the technology, to improve as a rider you still have to put in the effort.

While endless hours in the saddle may seem daunting, Oppy recommends changing ‘the venue of your rides in order to avoid monotony’.

‘One day it is advisable to pedal over a flat course, while the following day an undulating should be chosen. Plan your ride ahead and be interested in the thought of visiting a town, a mountain or a valley.

‘Short runs should be ridden in various ways—one day speed along at a smart pace, the next, alternate with slow riding and bursts of speed over a mile or so.’

Oppy’s recommended training regime for young cyclists was a distance of about 200 miles (300+ kilometres) a week to prepare for competition, so you can understand the need to keep things fresh if you are pedalling those distances.

But this advice was just a fraction of his own regime.

‘Oppy was doing over 800 kilometres a week in the lead up to his own events,’ says Matilda.

But with the roads being busier than ever, modern-day cyclists have the option of training without leaving home at all using virtual reality (VR).

In fact, entire road races have been held in VR during the COVID pandemic—professional athletes racing each other from the (relative) comfort of their own homes!

‘The rise in virtual online cycling programs have allowed people to not just ride their ergonomic trainers for training purposes, but connect with other cyclists all around the world,’ says Matilda.

Who could have imagined such a thing in Oppy’s time?

It makes you wonder what cycling will look like in another 100 years.