Five creatures ‘invading’ southern seas

On 14 April 2020, a winged giant was found floundering off a Melbourne beach.

It was a Japanese Devilray, a plankton-eater of warmer waters—and a long way from home.

The seas off south-eastern Australia are in the midst of great change. They are what Museums Victoria ichthyologist Dianne Bray calls an ‘ocean warming hotspot’, with temperatures increasing by three- to four-times the global average.

But the sea is vast and mysterious. A place of violent storms and ferocious predators. Its strange beasts and treasures have forever marooned upon our shores.

And the East Australian Current has long swept creatures down from the tropical north toward the temperate south.

So was the Devilray pioneering new territory for its species? Swept by currents out from its normal range? Or was this simply another rare event, the likes of which the sea has forever provided?

Di says a key to answering those questions is to establish if a species not only ‘overwinters’, but establishes a breeding population.

It is one thing for a tropical species to visit temperate waters. But is it a year-round resident?

And in order to answer that question, marine biologists need long-term data. They need a record of where a species has existed in the past, and to keep track of where it is in the present.

But there are lots of fish in the sea. And datasets like these need to be amassed over decades to tell a story.

So how do you fund such extensive record keeping, for so many species, over such long periods of time?

One answer is to enlist the army of fishers, divers, boaters, beach combers who collectively make Australians such a famously beach-loving people.

Which is exactly what RedMap does. The citizen science project enables sightings by volunteers to be verified by experts like Di.

‘It maps changes in species’ distributions, primarily due to warming oceans,’ Di says.

'But it records other changes.’

Launched in 2009, the project has now run for more than a decade. Below are five of the species whose changing distribution it is helping track.

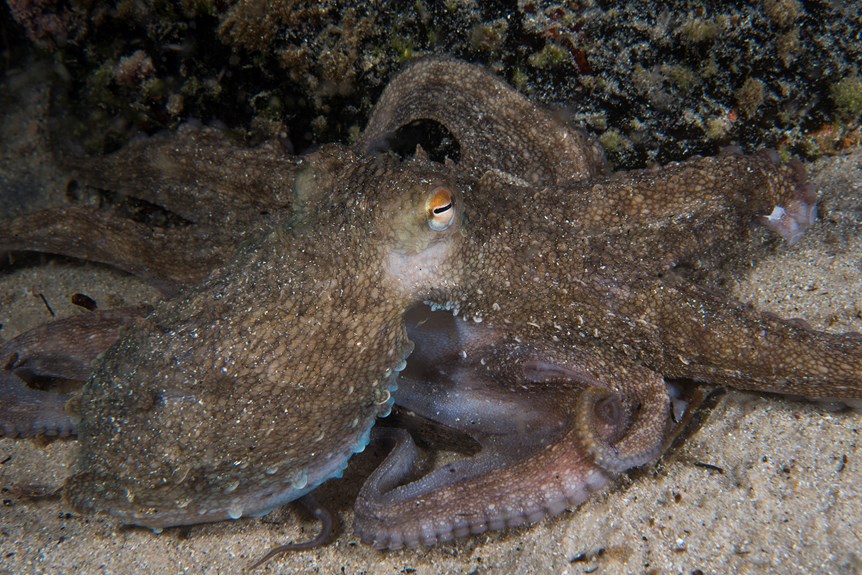

Gloomy Octopus

If an octopus is recorded on RedMap, it was probably verified by Dr Julian Finn.

The Museums Victoria marine invertebrates senior curator is an authority on cephalopods—octopuses, squids, cuttlefishes and nautiluses.

Julian says he has observed an influx of species coming down the east coast.

‘Probably the most worrying one, as far as cephalopods go, is the Common Sydney Octopus (Octopus tetricus),’ he says.

‘It seems to very good at eating a lot of things. It’s a very effective predator which occurs in very large numbers.

'From my observations, we don't really have that sort of octopus in Victoria.’

Snapper

Not all change, however, is all bad.

RedMap is tracking the southern expansion of Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus). But so are plenty of Tasmanian fishos—Snapper being one of Australia’s most prized table fish.

Researchers are still unsure if they are over-wintering or breeding in Tasmania.

Blue Groper

Nor is all change due entirely to climate.

Another driver of change in species’ distributions is the creation of marine sanctuaries and reduction in fishing pressure.

Overexploitation can cause a species numbers to decline from some areas. Conversely, conservation can see a species’ numbers increase.

There have been several verified sightings of Western Blue Groper (Achoerodus gouldii) in Port Phillip Bay over the last decade—though none prior.

The big blue males in particular are 'incredibly inquisitive and will swim right up to divers. Prior to the species being protected, this trait made them very susceptible to spear divers in places like South Australia.

States began protecting Western Blue Groper following declines in their numbers in the 1960s. The species is fully protected in Victoria.

The recent sightings might be a result of a recovery of the species, warming water or both.

Sea Urchin

The arrival of some species can devastate entire ecosystems.

The southern expansion of Long-Spined Sea Urchins (Centrostephanus rodgersii) into the biodiverse kelp forests of eastern Victoria and Tasmania has left barrens in its wake.

Blanket Octopus

The arrival of other species can bedazzle. Take argonautoids, a rare group of open ocean octopuses.

'They are this weird group of octopuses that have left the sea floor and have come up into the water column,’ Julian says.

'Probably the most exciting one is the Blanket Octopus (Tremoctopus).’

Females can grow to 2-metres with extended psychedelic banners of flesh which they drop like a lizard’s tail when chased. Males are the size of a five cent piece.

‘They are the most sexually size dimorphic member of the animal kingdom,’ Julian says.

'An unusual octopus, not unknown from our waters, but rarely seen and definitely on the increase.’