This small rock holds the story of Antarctic exploration before the Heroic Age

Discover the rock that unlocked one of the biggest mysteries of Antarctica and the incredible story of Carsten Borchgrevink, the Norwegian explorer determined to get there first.

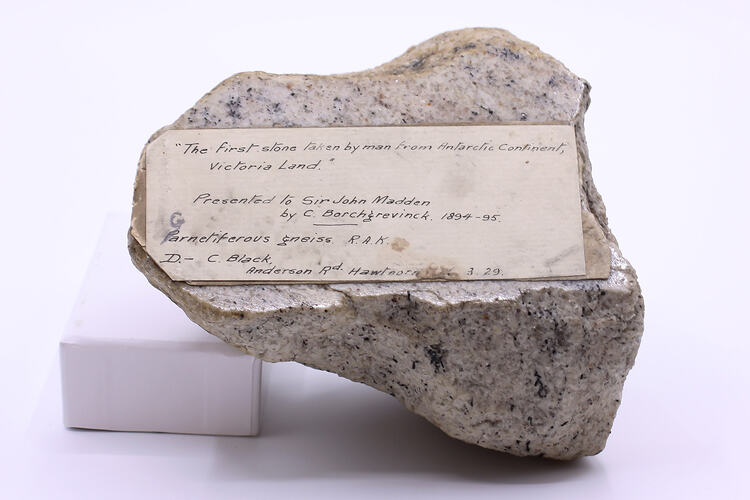

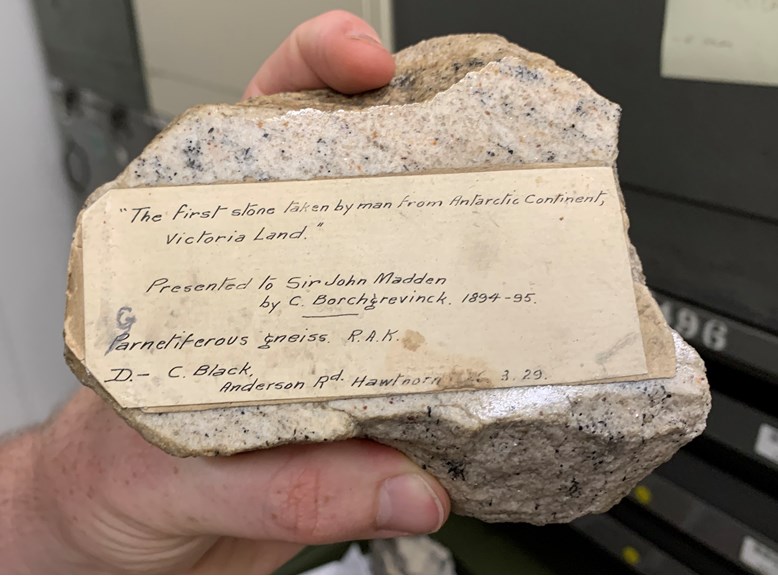

In a non-descript drawer in the corner of the Museums Victoria geology collection store is a rock which bears an extraordinary claim: 'The first stone taken by man from Antarctic Continent’.

Which raises some questions—how do we know if that’s true and, if it is, why does it matter?

‘What’s interesting about it from a historical point of view is that the kind of rock it is, is really typical of rocks that make up big continental landmasses,’ says Oskar Lindenmayer, the museum’s geosciences collection manager.

‘It’s a metamorphic rock, so formed under intense heat and pressure.’

We now know the ice and snow of Antarctica sits atop a rocky continent but scientists were not so sure at the time this stone was collected.

‘It was really the first evidence that there was potentially something like a continent in Antarctica,’ says Oskar.

Which might explain why someone would be so keen to label this as the first.

The date, listed as ‘1894-95’, puts it two years before what is commonly referred to as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Many famous names have claimed a first in Antarctic exploration—Roald Amundsen, Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, and Douglas Mawson are among the biggest.

This stone, however, was taken by one ‘C Borchgrevink’.

So, who is he, and how did this rock end up in the museum’s collection?

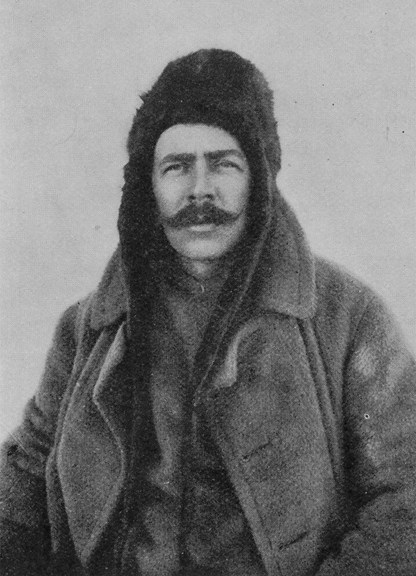

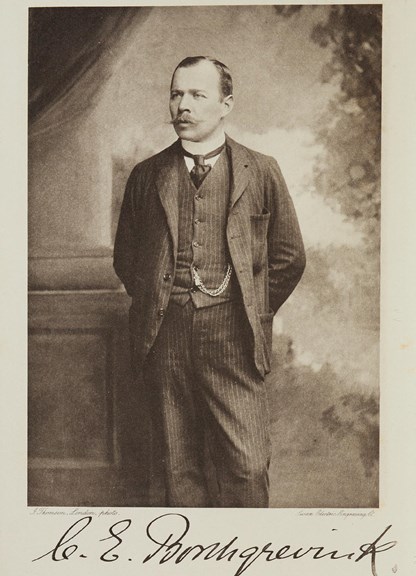

Carsten Borchgrevink: school teacher, explorer, Antarctic pioneer

Born in 1864 in Christiania (now Oslo), Norway, Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink was many things: an utterly dedicated Antarctic explorer, impressive moustache grower, and relentless self-promoter.

In an unlikely coincidence, the young Carsten Borchgrevink was a childhood playmate of fellow Antarctic explorer Roald Amundsen, who led the first party to reach the South Pole.

While Amundsen would go farther, Borchgrevink would get there earlier—twice!

But Borchgrevink’s route to be an explorer was far from straightforward.

He studied natural sciences in Germany before immigrating to Australia in 1888, in search of adventure.

The Royal Society of Victoria had established the Australian Antarctic Exploration Committee two years earlier, so it seemed like a good fit.

Instead Borchgrevink found work on survey teams in Queensland and New South Wales, before becoming a science teacher at the Cooerwull Academy, west of the Blue Mountains.

That was until he got his first break in 1894.

Fellow Norwegian Henryk Bull had organised an Antarctic whaling voyage to look for new hunting grounds, and took Borchgrevink on as a deckhand with permission to do scientific work.

The ship Antarctic set sail from Melbourne on 26 September, 1894.

After nearly four months of unsuccessfully hunting for whales, the ship arrived at Possession Island, just off the Antarctic mainland.

This is where he collected the first geological specimens in the area, including the first botanical life found within the Antarctic Circle, in the form of lichen.

‘I quite unexpectedly found vegetation on the rocks about 30 feet above the sea level, vegetation having never been discovered in so southerly a latitude before,’ wrote Borchgrevink.

This was an important discovery, as the Antarctic environment was previously thought too harsh to support this kind of life.

When the expedition did make it to the mainland at Cape Adare on 24 January 1895, the irrepressible Borchgrevink claimed to be the first person to set foot on the Antarctic continent.

‘I do not know whether it was the desire to catch the jellyfish (seen in the shallows), or from a strong desire to be the first man to put foot on this terra incognita, but as soon as the order was given to stop pulling the oars, I jumped over the side of the boat,’ he recounted.

Borchgrevink’s version of events, however, was contested by two others.

Leonard Kristensen and Alexander von Tunzelmann, who were also on the boat, both claimed the achievement as theirs.

Despite the conjecture over whose feet hit ground first, this was where Borchgrevink found this ‘first stone’.

‘One peculiar rock I collected has an indistinct granular structure, and resembles much the garnet sand-stone of Broken Hill; it seems to bear some close relation to granilite,’ he recounted.

‘The specimen is composed of quartz, garnet, and felspar fragments.’

Which is an exact match for this rock in the museum’s collection.

‘He wasn’t a geologist but he understood the importance of collecting these specimens and bringing them back to geologists who could understand and recognise their significance,’ says Oskar.

In this case it was T W Edgeworth David, Professor of Geology at the University of Sydney and later an Antarctic explorer, who made the connection between this rock and Antarctica’s continental status.

Following the ship’s return to Melbourne, Borchgrevink donated many of the scientific samples he collected to Melbourne's Industrial & Technological Museum,whose geological collections were later transferred to Museums Victoria.

The ‘first stone’ though, he gave to Sir John Madden—a high court judge, who also happened to be the Vice-Chancellor of Melbourne University.

‘I suspect that’s why he would have been given this material, in his capacity as a senior person in the academic world of Melbourne,’ explains Oskar.

Eager to capitalise on his success, Borchgrevink tried to secure support for a second expedition.

‘He went on a speaking tour of the learned societies of Melbourne and Sydney,’ says Oskar.

Unable to secure funds in Australia for another voyage, Borchgrevink headed to England.

Second voyage and the beginning of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

Borchgrevink found a more receptive audience for his writings and presentations of scientific discoveries in London.

‘Neither ice nor volcanoes seemed to have prevailed at the peninsula at Cape Adare, and I strongly recommend a future scientific expedition to choose this spot as a centre for operations…I myself am willing to be the leader of a party,’ he told the Sixth International Geographical Conference, in 1895.

But it took several years for his plans to eventuate.

Meanwhile, a Belgian expedition aboard the Belgica, led by Adrien de Gerlache, left for Antarctica in 1897—the first dedicated scientific voyage of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

After drumming up enthusiasm for the English geographical authorities to plan their own expedition though, Borchgrevink was impatient to get moving.

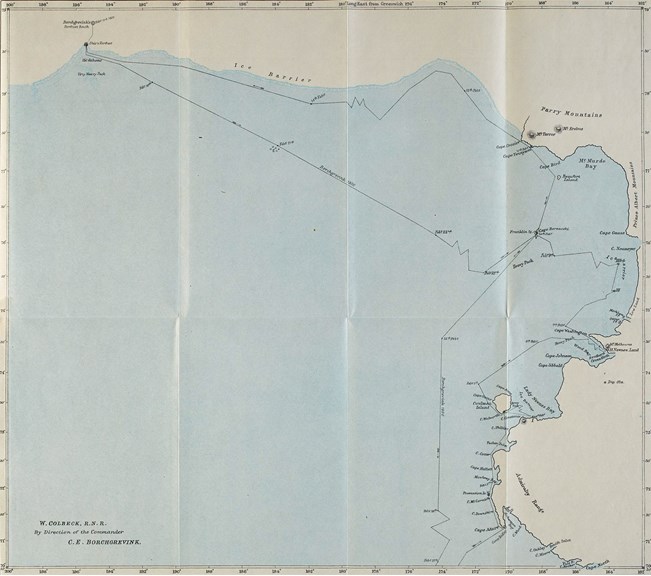

He secured funding from his publisher, Sir George Newness, and bought a ship which he renamed Southern Cross.

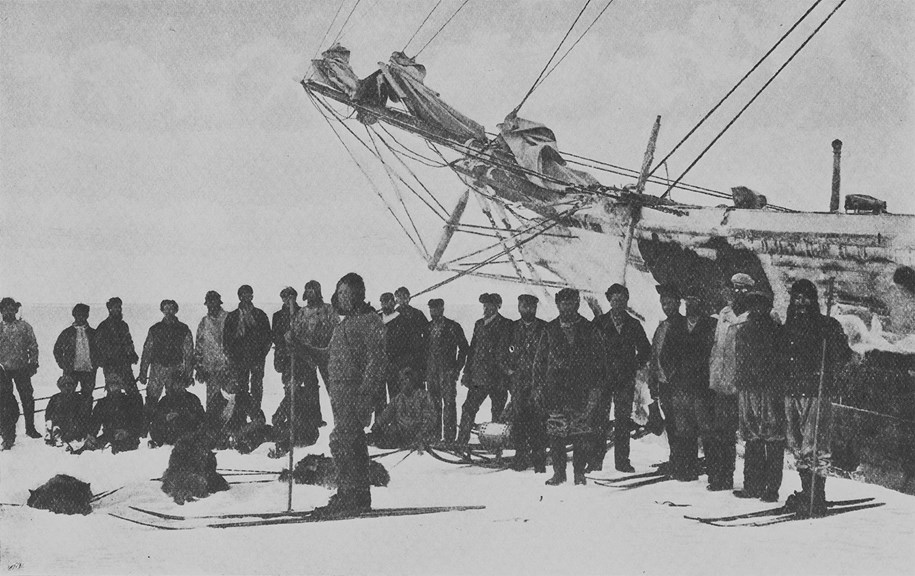

Borchgrevink’s crew of 31 men and 90 dogs set sail, stopping off in Hobart, before making the final leg of the voyage to Antarctica.

By this time the Belgian expedition had already returned, having failed to reach the Antarctic continent, but Borchgrevink was not entirely dismissive of their efforts.

He wrote, ‘that expedition was the first to over-winter in within the Antarctic Circle. However, the first to invade the Antarctic Continent were the members of the Southern Cross under my command’.

Of his own landing, at Cape Adare, Borchgrevink was keen to highlight its importance to global exploration.

‘At 11pm on the 17th February, 1899, for the first time in the world’s history an anchor fell at the last terra incognita on the globe,’ he wrote.

The crew of the Southern Cross spent a year in Antarctica, becoming the first people to spend the winter on the continent.

It was also the first expedition to use dogs in Antarctica—something that would continue for another century.

Borchgrevink’s expedition recorded meteorological conditions, new species of Antarctic flora, and the approximate location of the south magnetic pole.

After his return to England, Borchgrevink published his memoir, aptly titled First on the Antarctic Continent, in 1901.

However, his pioneering achievements were not well recognised in England at the time.

‘I suspect he annoyed a lot of his contemporaries,’ says Oskar.

‘He was out there really trying to get things to happen immediately and that might have undercut some of the more methodical expeditions that happened later.’

He was made a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society but, notably, was awarded much higher honours from other nations.

One such honour was bestowed upon Borchgrevink by the King of Norway, who appointed him a knight of St Olav.

The Royal Geographical Society did eventually recognise Borchgrevink, awarding him its Patron’s Medal in 1930.

By that time the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was well and truly over and his achievements had been overshadowed by more celebrated journeys.

The subsequent explorers of that era relied on Borchgrevink’s pioneering work, which all began with that ‘first stone taken by man from Antarctic Continent’, in 1895.

‘He didn’t come up with groundbreaking ideas necessarily, but he was able to be in the right place at the right time,’ says Oskar.

‘That allowed others to make the big conceptual leaps and, for instance, realise that there might be a continent down south of Australia.

‘He represents a bridge between the purely economically focused expeditions that had been going on earlier—sealing and whaling voyages—to the more national pride expeditions.

‘His seems to be, to my mind, more a story of personal accomplishment.’

Is it really the first stone from Antarctica?

As for the stone itself, Sir John Madden passed away in 1918 and it passed by unknown means to Cecil Brack—a local councillor in the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn.

It was Mr Brack who then donated it to the National Museum of Victoria (a forerunner to Museums Victoria), in 1929.

So how can we be sure it is genuine after it spent three decades in private hands?

‘It does match very closely to one of the small chips of rock that was donated directly by Borchgrevink to the Industrial and Technological Museum in Melbourne,’ explains Oskar.

‘We have quite good reason to think that they are essentially pieces of the same rock…that’s another piece of evidence that this isn’t just a made-up story.’

But the type of rock also gives us some indication of its provenance.

‘Of the rocks that we have from that first expedition by Borchgrevink this is the only one that, without a doubt, must have come from the Antarctic mainland,’ says Oskar.

‘The other rocks we have are volcanic rocks, some of which have been ascribed to being collected on Possession Island, which is just off the mainland of Antarctica.

‘There’s reasonable evidence this was amongst the first, if not the first rock to be collected from Antarctica, by that expedition.’

The thing is, by the time it came to the museum, it had been cut and polished and a label affixed to the surface.

So do we know where the rest of it could be?

‘There’s a report of the King of Norway being given a rock that’s been described similarly—a microcline granite.’

‘It’s plausible that that’s another piece of the same rock.

‘We do know of some other selections of rocks from that first Borchgrevink expedition in other museums.

‘They don’t have that continental affinity that is so significant about this one, but potentially the one owned by the King of Norway does share that.’