Catching Lightning

A fulgurite that took microseconds to form, a moment to break and over 50 years to reassemble.

“You can’t catch lightning in a bottle” is a common expression - it’s an idiom that describes achieving the seemingly impossible; to capture and distil a fleeting, elusive and powerful moment and save it for posterity. In a sense, it is true – the massive electric discharges of 100 million volts or more don’t seem to lend themselves to being contained. But what if lightning can be kept in other ways, as a frozen moment of intense energy?

As it turns out, lightning strikes occur with frightening regularity – estimated to occur as frequently as ten times every second somewhere on Earth. Far less regularly though, the moment of a lightning strike takes a physical form, where it is frozen perfectly in sandy soil producing a trace structure called a Fulgurite.

When an intense lightning strike occurs under the right conditions on the correct type of surface geology, the moment of discharge is of such intense energy that it partially melts and fuses grains of sand as the charge enters the earth. This creates a bolt-shaped structure of glassy, irregularly branching tubes that echo the same serpentine shapes we see crackle across the sky during thunderstorms. It may not be in a bottle, but it is a way of catching lightning.

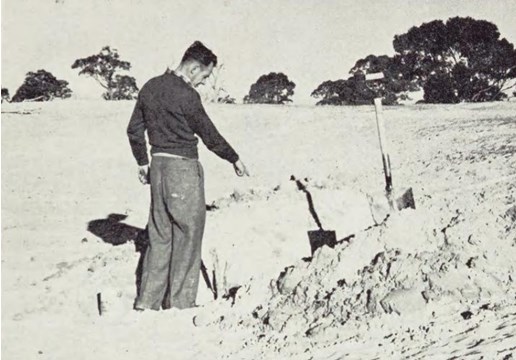

In 1959, Victoria’s longest recorded specimen of a Fulgurite was discovered in sandhills near the tiny settlement of Karnak, west of the Grampians in Western Victoria. In the sandy soils of the property of Mr J. F. Armstrong, an odd, tiny tube was noticed poking above the surface by Armstrong’s colleague, Mr. H. Keys. After more close and careful inspection, Messrs. Keys and Armstrong felt they’d made an interesting discovery, and wanted to know more, so it was brought to the Museum for identification. The specimen reached the attention of the then-Curator of Minerals, A. W. Beasley, who swiftly determined it to be a Fulgurite. With its identity confirmed, Keys and Armstrong were keen to find more of the ‘frozen lightning’, and eventually they discovered a specimen of over 1.5 metres at the same site in Karnak.

The Karnak fulgurite was formed by a discharge of lightning penetrating and fusing the quartz sand along its path. These intricately-branched glass tubes created by electrical discharge are notoriously brittle and thin walled, making a Fulgurite amongst the most difficult items to store and care for, even in a Museum. Moments after the initial discharge, the molten glass tubes contract and cool at varying rates, producing countless tiny, fine cracks on the structure, often resulting in the specimen breaking into segments along the countless lines of weakness.

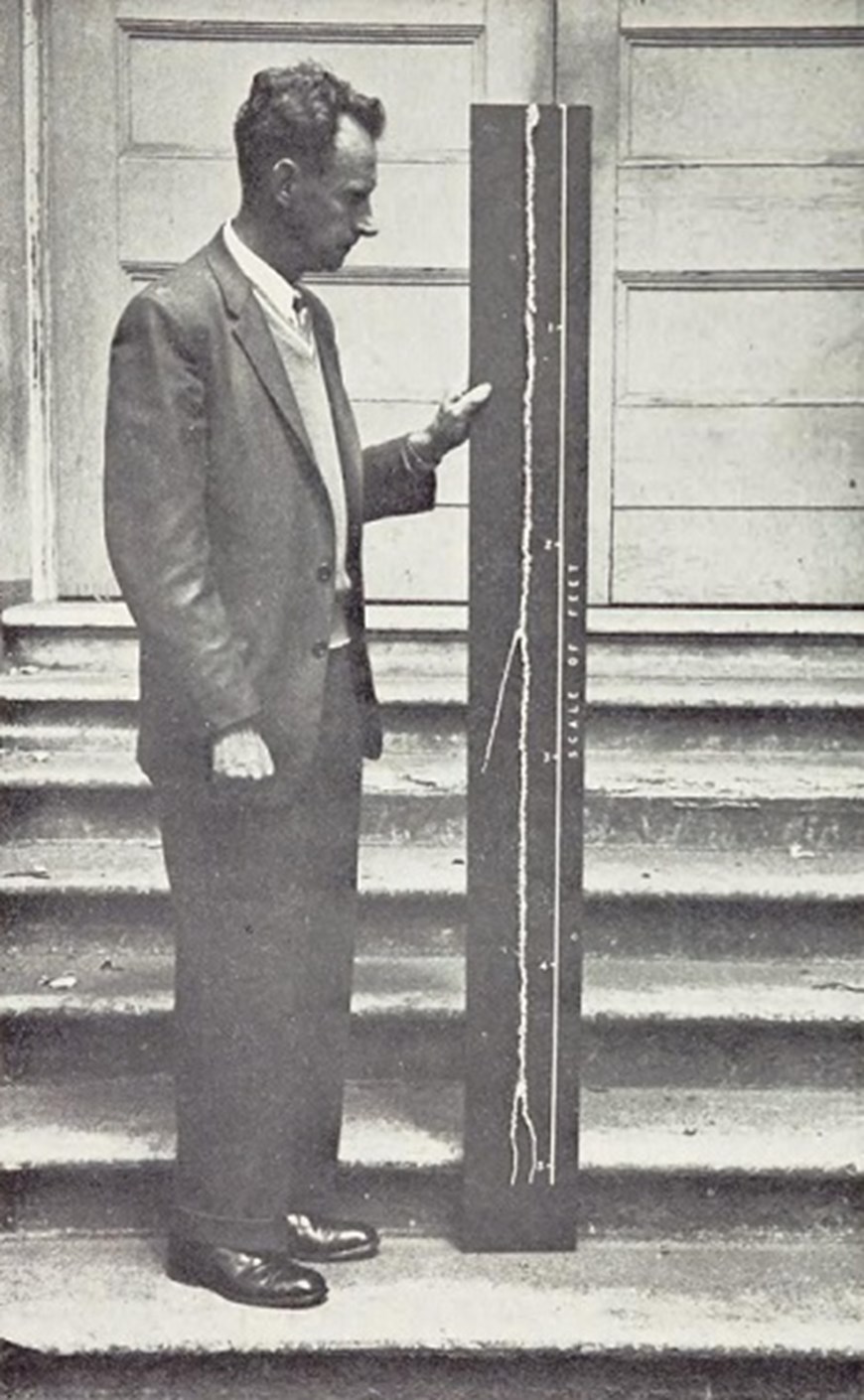

Because a lot of this was already known about Fulgurites in 1959, The Karnak fulgurite was extracted with the care and precision by Keys and Armstrong. Once fully extracted, numbered, documented and packaged, it was brought back to the Museum, where it was reassembled for display, again by Keys and Armstrong. A. W. Beasley documented the remarkable item in the “Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria” in 1963, complete with measurements, images and angles – data that would later prove invaluable. For nearly three decades the Karnak Fulgurite remained on show in the old campus of the Museum. Then in 1990, perhaps inevitably, disaster struck.

Source: Museums Victoria

While being unmounted and removed from display in 1990, the usually careful staff needed to apply a slight amount of pressure on the structure to remove it cleanly from its mounting board – an adhesive used back in the 1960 had become unstable over time. The tiniest amount of stress proved too much for the delicate structure, and it shattered into over 200 fragments. The shards were collected and stored in tiny vials for another 30 years.

Over 220 fragments we stored for posterity in the Mineralogy collections, bearing 5 different registration numbers, the lightning remained bottled, shelved and in hundreds of shards.

Then in 2016 the skilled and dauntless Museums Victoria Conservators, Dani Measday and Sarah Babister, looked upon the vials of bottled lightning and wondered – what if it was rebuilt? They decided to tackle the task of reassembling nature’s most nightmarish jigsaw puzzle using the invaluable, meticulous published work of Dr. Beasley’s description from 1963 as a guide. Keys and Armstong did not appear to document their extraction process with field notes, and without Beasley’s paper, the Conservator’s task was akin to attempting a fragile, three-dimensional jigsaw without so much as a box or a picture as a guide.

The story is more complicated and fascinating than simply reassembling the pieces using Beasley’s photography, though – our Conservators decided that if it was worth doing, it was worth doing properly, and using specialist technology to full effect, they were to solve a puzzle of geological marvel with forensic accuracy.

As a starting point, the Conservators made contact with the Museum’s own Archives team, and together they were able to discover some correspondence between Beasley and the property owner at Karnak– and perhaps surprisingly, it was established that there were a number of fulgurite finds, not just the single item damaged during the deinstallation back in 1990. The correspondence also revealed a valuable asset - a timeline, which was also helpful in decoding the otherwise confusing numbering system in the cataloguing. So, it became apparent that there were pieces from a number of puzzles in this particular jigsaw box!

Source: Museums Victoria

Photo: Benjamin Healley

Armed with these lines of evidence, the Conservators sought to reconstruct the displayed fulgurite piece by piece. Using a similar approach to forensic scientists, they tested each fragment for chemicals used in the consolidating and display of the fulgurite from more than 30 years prior. The presence of tiny fragments of black and pink paints helped narrow down the pieces that were on the display until 1990, as well as infrared spectrographic analysis to work out what adhesive materials were present. This helped sort out the once-displayed material from the additional samples.

Using Beasley’s description and images from 1963, the fulgurite was finally mapped, piece by piece, onto a large sheet of tracing paper over a foam backing to help guide with the reassembly. Fragments of similar size and colour were grouped together to establish any obvious sequences of pieces, and when discovered, they were held in position using dressmaker pins. Sarah and Dani soon discovered that some matching edges of Fulgurite fragments had clean breaks, while others were less easy to align with corresponding pieces; this is where the results of the infrared analysis guided the placement of the fragments.

Source: Museums Victoria

Photo: Benjamin Healley

Another consideration for the team was future-proofing the fragile fulgurite – what could be done to make reassembly easier should the unthinkable ever happen again? The focus was on careful, precise documentation - once the Conservators were satisfied with the layout, each fragment was numbered with a tag on a pin, then photographed from both sides with additional annotations on the photos. Dani and Sarah started the next painstaking task of sticking the pieces together, using reversible adhesives just in case future research reveals details that need to be corrected. Dani and Sarah determined the safest form of the reassembled fulgurite was in three pieces – a valuable lesson was learned from the previous display, as handling large segments of ‘frozen lightning’ is, predictably, not straightforward!

So, after months of meticulous work - research, forensic analysis and steady hands, the fulgurite was reassembled – and a branch of a solid lightning bolt was freed from its bottle. It took milliseconds to form, years to display, a brief moment to break, and months of forensic expertise to bring the bolt back. Long may it remain unshattered!

Source: Museums Victoria

Photo: Benjamin Healley

Further reading