Backyard ballistics: Australia's first DIY satellite

Fifty years after its launch aboard a NASA rocket, Australis OSCAR 5 stands as a monument to backyard ingenuity.

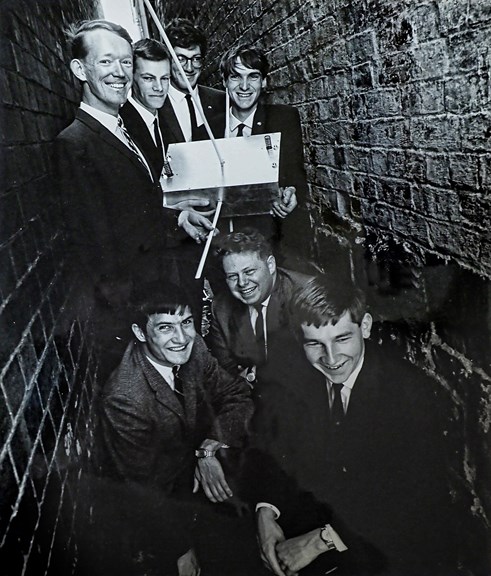

The year was 1965 and the United States and Soviet Union were joined in a space race by a new player. It was not a rising superpower, however, but a group of Australian university students.

Unlikely as it may seem now, this team of self-described nerds, ham radio operators and astronomy buffs appeared destined to build Australia’s first satellite: Australis OSCAR 5.

Among them was Peter Hammer, at the time, a bedroom electronic tinkerer.

The world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was designed by Soviet rocket scientists. The USA's first satellite, Explorer 1, was built in a missile base.

The first satellite Australia built, however, would be conceived in bedrooms and trialled on rooftops by teenagers and students in their 20s.

'It was very much a backyard satellite.'Peter Hammer

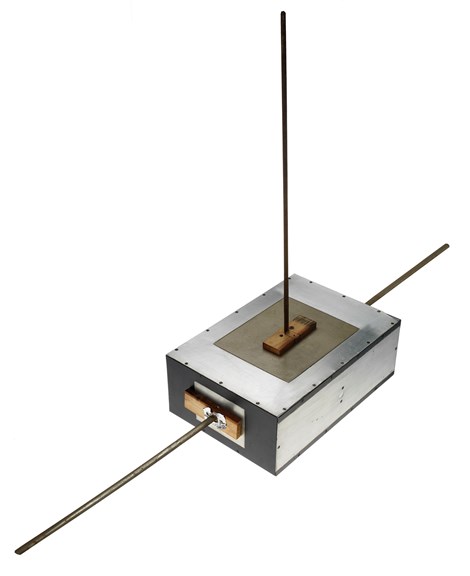

AO5—as it is abbreviated—is an unassuming looking spacecraft.

An aluminium, rectangular box about 30-centimetres wide and less than 1.5-metres long, its most striking feature is its antennae, which are repurposed, steel measuring tape of the kind used by carpenters and bought in hardware stores.

Peter etched the satellite's copper circuit boards using a hobby technique involving ferric chloride and nail varnish. It was heat-tested in a share house oven and cold-tested in the freezer of Melbourne University's glaciology department.

Without government support, AO5’s components were ‘begged and borrowed’—its springs custom-made by a sympathetic Footscray factory owner and circuitry picked up in electronic stores which dotted the city at the time.

Owen Mace was 19 when he took on the unofficial role as AO5’s project manager. Like Peter, he was a member of the University of Melbourne’s astronautical society and radio club.

He says that the suburban nature of A05’s construction led to a number of technical innovations.

‘There was no manual.'Owen Mace

‘Neither the Russians nor the Americans were very forthcoming with technical details, they didn’t want the other side to learn their secrets.’

So the students had to proceed from first principles.

‘We had lots of grand ideas,’ Owen says.

‘But we realised that we would have to scale them back. So we did—and it resulted in some unique things.’

Among the problems that needed to be solved was how to stabilise AO5’s antennae in the tumble of space.

‘We had just done lectures in magnetism and we thought, ‘why can’t we use Earth’s magnetic field to stabilise Australis?,’ Owen says.

As it turned out, they could, and AO5 was the first satellite to do so, he says. It was also the first amateur satellite to be controlled remotely and further developed telemetry, or the signals used by satellites to communicate data.

Construction, of course, is only the first step in a satellite’s journey. There’s also the getting it into space part.

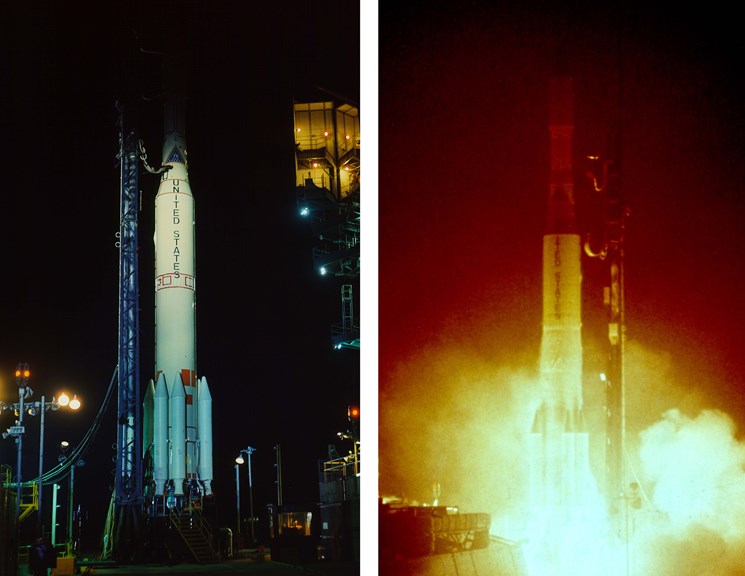

A05 was originally planned to be launched in late 1966 by the United States Air Force as part of the Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio project—or OSCAR— project.

Had everything gone according to plan, A05 would have been the first Australian satellite to reach space.

But OSCAR fell apart and, with it, AO5’s chances of a launch.

The satellite was shelved and the Australian government's Weapons Research Establishment satellite, WRESAT, pipped A05 to the post.

WRESAT was launched in November 1967 at Woomera, South Australia, and became the country’s first orbiting satellite.

Then, from the ashes of OSCAR, a new amateur radio satellite organisation was born—AMSAT, based near Washington D.C.

AO5 became its first project and on 23 January 1970, aboard a NASA Thor Delta rocketship, Australia's backyard satellite was launched.

For several weeks, AO5 was tracked by over 200 radio amateurs in 27 different countries.

Then, on 9 March 1970, it went silent, its batteries exhausted.

The students would go on to work in aeronautical industries, head university departments and build more satellites.

Fifty years on, some have retired, others passed away. But A05 continues its silent orbit.

‘It’s estimated lifetime in orbit is 100,000 years,’ Richard Tonkin, another of the A05 team, says.

‘Space junk to some, but a national treasure to us.’Richard Tonkin