10 really big things in the Museums Victoria State Collection

With millions of objects to choose from, what are the some of the biggest things in the museum's collection?

Though most people don’t see it in its entirety, the Museums Victoria State Collection is BIG.

In fact, we need several buildings to hold it all.

Since 1854 it has grown to include more than 15 million items—everything from dinosaur fossils, scientific specimens and technological marvels to significant pieces of Australia’s history.

So, given it’s such a big collection, what are some of the biggest things in it?

Phar Lap

Equally famous for his heroics on the track and the mystery surrounding his death in 1932, Phar Lap looms large across the history of horse racing.

His success as a racehorse in the early years of the Great Depression have echoed down the years, and to this day he remains one of the Melbourne Museum’s most popular attractions.

Measuring in at 17 hands (just over 1.7 metres tall) Phar Lap was big for a horse, and not just on the outside—his heart weighed 6.5 kilograms, almost double the average for a thoroughbred.

However, Museums Victoria only has his taxidermy mount in its collection.

Phar Lap’s massive heart resides in the National Museum of Australia, in Canberra; his skeleton is in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the country of his birth.

A chimney

You may well ask, ‘What’s a chimney doing in the museum’s collection?’.

This seven-metre-tall brick chimney is from the dining room of ‘The Uplands’ homestead in Kinglake, built in the 1890s, that was destroyed in the Black Saturday Bushfires in February 2009.

The homestead was a meeting place for the local community, but the chimney was all that was left standing after the fire.

In a very carefully-planned operation, contractors dismantled the chimney and its hearth brick by brick.

All 1500 bricks had to be individually numbered so it could be reconstructed back at the Melbourne Museum, where it now stands in the Forest Gallery amongst towering gum trees—a permanent memorial to those lost in Black Saturday as part of the museum’s collection.

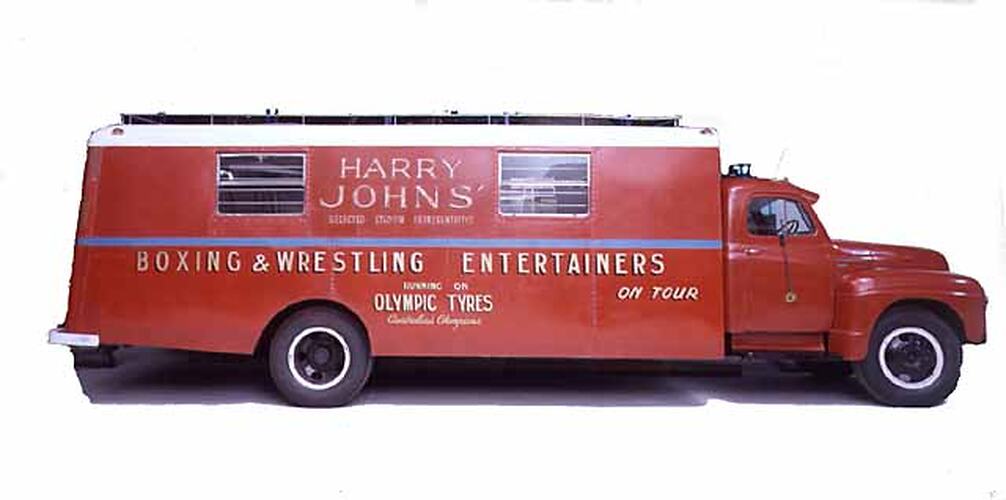

Boxing troupe truck

Not just a relic of the past, this truck was used by Harry Johns—a boxing and wrestling entrepreneur.

He and his troupe toured agricultural shows in Australia's eastern states between the 1930s and 1960s.

This 8.8-metre-long truck started out life as an International AR Series 160 in 1954 but the flatbed was replaced by Johns, who grafted the rear body section from his previous truck.

It had to be that big to fit in all the equipment and people required to travel from show to show, but it also had the benefit of acting as a rolling advertisement.

Boxing was an important aspect of Aboriginal culture in the 1900s—seen as a way of escaping mission life and raising political and social awareness during the time of the White Australia Policy.

Many of the boxers who travelled with the Harry Johns troupe were Aboriginal fighters.

Harry Johns Jr and Francesca Rose donated the truck to the museum in 1996 and it has been restored to the condition in which it was last used, in 1969.

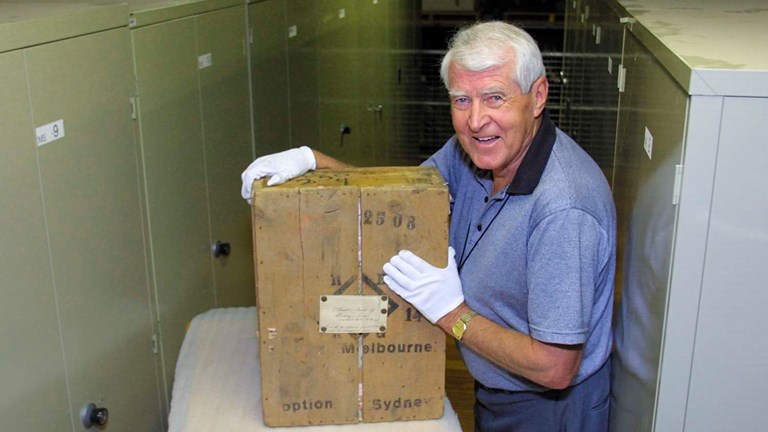

Great Melbourne Telescope

A monument of 19th century engineering, the Great Melbourne Telescope was once the largest fully steerable telescope in the world.

Pointed straight up the telescope stands 10 metres tall, but its size is more accurately measured by the diameter of its primary mirror which is a massive 1.2 metres across.

Built in Ireland, it was first erected at the Melbourne Observatory in 1869 before being moved to the Mount Stromlo Observatory, near Canberra, in 1945.

The telescope was updated several times and assisted in the search for Dark Matter in the 1990s, before it was badly damaged by a bushfire in 2003.

Funnily enough, one of the pieces that was completely destroyed by the bushfire was a relatively modern addition—a Pyrex glass mirror installed in the 1960s, that was supposed to be heat proof.

The cast iron spine survived and is in the process of being restored to its former glory by a dedicated team of volunteers, students, and museum staff.

While it is not on display, you may be able to catch a glimpse of the Great Melbourne Telescope in the workshop viewing bay at Scienceworks.

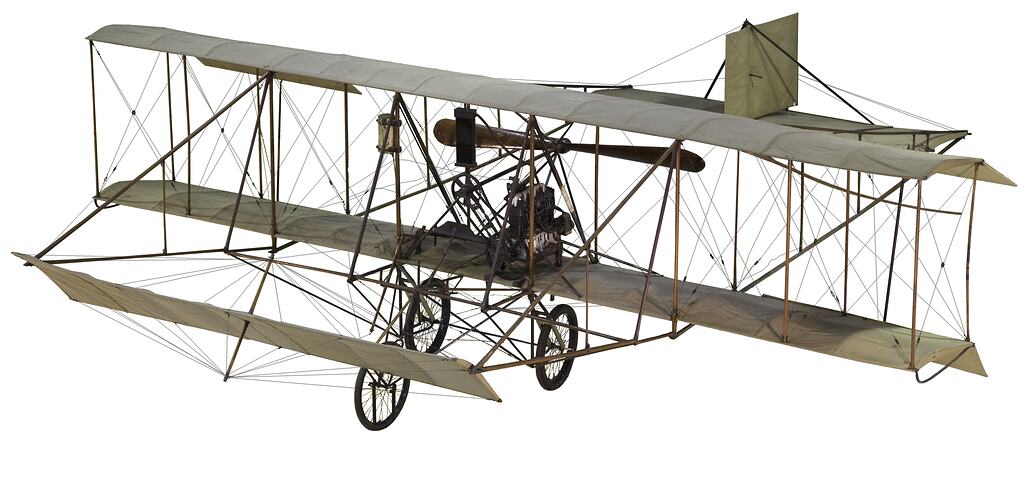

Duigan Biplane

This was the first Australian designed and built aeroplane to achieve controlled, powered flight more than 100 years ago—and it was built in country Victoria!

A 28-year-old John Duigan designed and constructed the 11.6-metre-long aircraft (with a wingspan of 7.4 metres) from wood, metal and rubber coated cotton fabric with his brother Reginald at their family farm at Mia Mia.

What’s remarkable is that Duigan had never seen or flown an aircraft before.

His first design was a glider based on a postcard photograph of the Wright Brothers’ Flyer, which he ‘flew’ in strong winds by tethering it to the ground with 110 metres of fencing wire.

The biplane followed and made its first flight in 1910.

It was donated to the museum in 1920, and while eagle-eyed visitors to the Melbourne Museum may think they have seen it suspended from the foyer ceiling, it’s actually a replica built in 1995—the real Duigan Biplane remains tucked away in one of our collection stores.

A giant squid

A big creature that has inspired big ideas for generations, giant squid are thought to be responsible for myths of ancient sea monsters.

While they don’t grow quite as big as the legends, a giant squid is still quite an imposing creature—the Melbourne Museum’s specimen is 12 metres long!

In fact, the museum’s collection contains a few specimens of similar size, but the one most people will be familiar with is the one on display in the Marine Life gallery.

It was found at a depth of 800 metres off Tasmania’s west coast.

If their size alone isn’t enough to impress you, giant squid also boast the largest eye of any animal—it can grow up to 27 centimetres in diameter, or about the size of a standard frying pan.

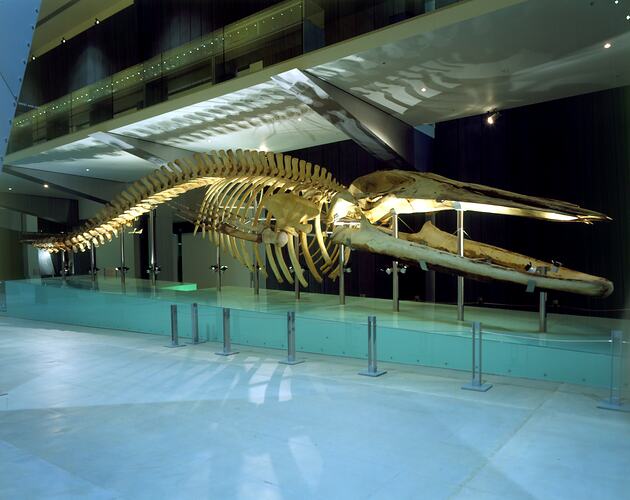

Blue Whale skeleton

We couldn’t have a big list without the largest species on earth—the Blue Whale.

Familiar to anyone who has visited the Melbourne Museum, this 18.7-metre-long skeleton once belonged to a male that washed ashore near Lorne, on Victoria’s west coast, in 1992.

It took a massive effort to collect the whale and prepare it for display and, while the Melbourne Museum’s isn’t small by any stretch of the imagination, it’s actually of a smaller subspecies—the Pygmy Blue Whale.

True Blue Whales can grow even larger, up to 33 metres long.

Nearly driven to extinction by whalers in the 19th century, Blue Whale numbers are slowly recovering but skeletons like ours ensure the plight of these graceful giants is not forgotten.

A giant sauropod

It would be a poor catalogue of big museum objects that didn’t include a dinosaur, so here it is—a 20-metre-long Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis that spends its days towering over the Dinosaur Walk exhibition at the Melbourne Museum.

This giant sauropod lived in the Late Jurassic period, in what is now China.

The museum’s specimen is a cast from a skeleton found in Sichuan province, in 1957, and has been in the museum’s collection since the late 90s.

Mamenchisaurus is famed for having the largest neck-to-body ratio of any dinosaur, which it managed with a series of ligaments anchored at the hip.

It also had spoon-shaped teeth to strip leaves from trees—a handy tool for an animal that had to eat continuously to sustain its massive form.

For a closer look at this giant, and some of the other dinosaurs on display, take a virtual tour of Dinosaur Walk.

Steam pumping engine

Of all the many and varied engines in the museum’s collection, this is one of the biggest—much like an iceberg, only a fraction of its 23.9 metre depth is visible above the ground.

It is also a piece of technology any 20th century resident of Melbourne would have been grateful for because it is an integral part of the Spotswood Pumping Station, which played a big part in saving the city from the moniker ‘Marvellous Smellbourne’.

For nearly 70 years all of Melbourne’s raw sewage passed through the pumps at Spotswood on the way to the Werribee treatment plant.

The first quarter century of its operation was driven by steam-powered engines like this one—a Hathorn Davey Engine, built in the UK, and installed in 1901.

The first electric pumps were installed in 1921, and this engine was last used in 1925.

It’s now the oldest of the five remaining steam-powered engines in the Pumping Station, and the oldest engine of this type and make in the world.

You can take a virtual tour of the Pumping Station here.

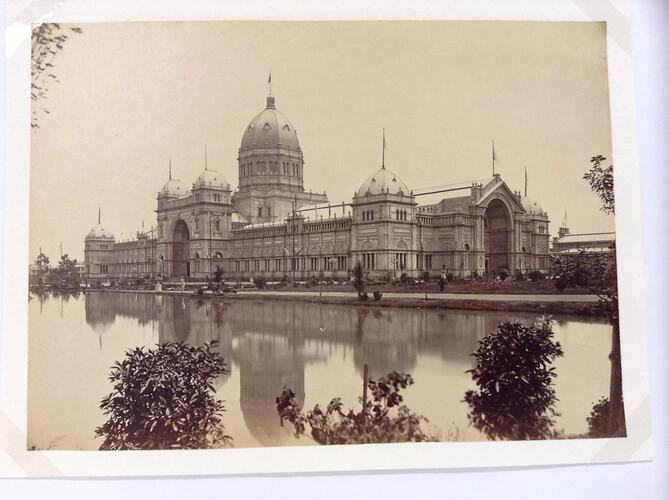

The Royal Exhibition Building

Last, but by no means least, it’s the biggest of them all—the Royal Exhibition Building!

I know, you’re probably thinking, ‘Hey that’s cheating! A building doesn’t count’.

But this iconic structure is one of Victoria’s most significant heritage buildings, and the only one that’s world heritage listed.

A true Melbourne icon that continues to serve the same purpose that it did when it was first opened in 1880—although along the way it has also had a varied career as a barracks, migrant reception centre, federal parliament and vaccination hub.

At 150 metres long, it’s easily the largest thing in the museum’s care and, if we were so inclined, could house all the other things on this list!

3D model created by CyArk with the support of Iron Mountain

Looking for more? You can explore our Collections Online.